The Long Decline In Yields Has To End… Eventually

The 10-year Treasury yield yesterday took a breather from plumbing new record lows, but it’s not obvious that the 35-year slide in interest rates is over. The benchmark rate ticked up to 1.40% yesterday (July 8) via Treasury.gov’s daily data, a whisker above Monday’s all-time low of 1.37%. All the usual caveats apply for deciding if even lower yields are coming. But if the rest of the world offers a clue (such as the expanding tide of negative rates), it’s premature to bet against a multi-generational trend that’s confounded almost everyone who studies the bond market.

The slow grind lower in 10-year yields, in the US and around the world, is the byproduct of a powerful secular forces that have been fueled by several factors through the years. From financial crisis to recessions to fears of deflation and stumbling growth and the liquidity injections from central banks, the inexorable decline in the price of money has been a staple on the financial landscape since Ronald Reagan sat in the White House. At almost every step of the way, pundits have declared that the jig was up and rates were due to soar, and every time they’ve been wrong. Maybe it’s finally different this time, but the hints that growth everywhere is decelerating doesn’t make a convincing case for expecting the 35-year-old bull market in Treasuries is about to hit a wall.

Larry Summers’ secular stagnation thesis, in other words, is alive and well. “Extraordinarily low rates reflect both subtarget expected inflation even over long horizons and very low real interest rates,” advises the former Treasury Secretary.

The Fed Funds futures market provides a window into market thinking regarding the likely path of monetary policy. Remarkably the market does not now expect a full Fed tightening until early 2019. This is despite all the Fed speeches expressing optimism about the economy and a desire to normalize interest rates.

I believe that these developments all reflect a growing awareness of the importance of the secular stagnation risks that I have highlighted over the last several years. There is a growing sense that the world is demand short—that the real interest rates necessary to equate investment and saving at full employment are very low and may be often unattainable given the bounds on nominal interest rate reductions. The result is very low long term real rates, sluggish growth expectations, concerns about the ability even over the fairly long term to get inflation to average 2 percent, and a sense that the Fed and the world’s major central banks will not be able to normalize financial conditions in the foreseeable future.

Is the remarkable set of factors that brought us to this point about to evaporate and deliver the secular U-turn in yields that bond bears have been predicting for years? Don’t hold your breath. There’s enough growth in the global economy to keep a new recession at bay, at least for the near term, but the odds are still low that the macro trend is poised for an upside breakout any time soon. Instead, there’s more of the same, modest growth that’s showing signs of age.

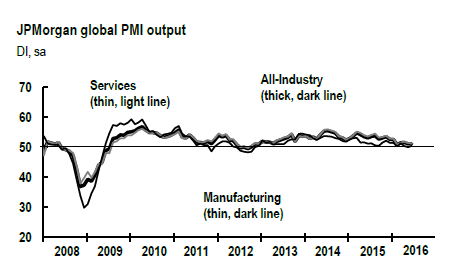

“The global economy recorded its weakest growth of both output and new orders since the end of 2012 during the second quarter,” Markit Economics reported earlier this week in its monthly update of the J.P.Morgan Global Manufacturing & Services PMI. “The lackluster economic performance was again reflected in the labor market, with the rate of increase in payroll numbers sliding to the lowest for almost three years during June.”

Today’s employment report for the US in June is expected to bring some relief, but only in relative terms vs. the dark expectations that were unleashed with the dismal numbers for job growth in May. But if you look past the noise in today’s figures, you’re likely to find a familiar and worrisome trend in the employment data: softer year-over-year growth, which was the main takeaway in yesterday’s ADP Employment Report for last month.

Yes, it’s late in the game to be betting the farm on bonds. After 35 years, 98% of the yield decline is behind us, which implies that it’s safe to be a contrarian. But the analogy of falling off a 1,000-foot cliff comes to mind: it’s only the last foot that hurts.

Disclosure: None.

This doesn't even take into account the massive demand for bonds as collateral in the derivatives markets. Because of the need for all this collateral, it cannot be allowed to decline in value. Therefore, growth must be slow to protect all the financial institutions committed to this collateral. It is such an exercise in madness that normal is now craziness. Any real growth would force central banks to undermine the collateral by raising rates and lowering price.

Yes derivatives are the whale in the coal mine. When the mess is discovered it is going to be very ugly, very smelly, and very toxic. I suppose that's one reason the Federal Reserve is insistent on not even allowing a mild recession from happening. Sadly that only increases the change for a bigger one later.

The Fed can handle recession. It cannot handle white hot prosperity. It cannot raise rates to slow the train down because it would destroy the collateral.

You bring up a very secret point about the managed economy. You are quite right that TBTF banks and the central bank, although not talked about openly, don't want strong growth which would require an end of QE, Zirp, create inflation, and lower asset prices. That is why Japan's ruling party doesn't want it either.

In effect, it transfers wealth from banks to ordinary citizens. Mon dieu, we can't have that.

That is why, to offset this obvious scheme, central banks must consider helicopter money to help the real economy and get rates to move a little higher.