The Great Unwind Begins

The Federal Reserve announced today that it will begin reducing the size of its balance sheet next month in very modest and deliberate steps. One reason the Fed is moving so slowly is that they don’t want a repeat of the May 2013 taper tantrum, in which a surprise hint that the Fed might slow the rate at which it would be growing its balance sheet led to a spike up in long-term interest rates. But there may also be another reason why the Fed is contracting its balance sheet so cautiously.

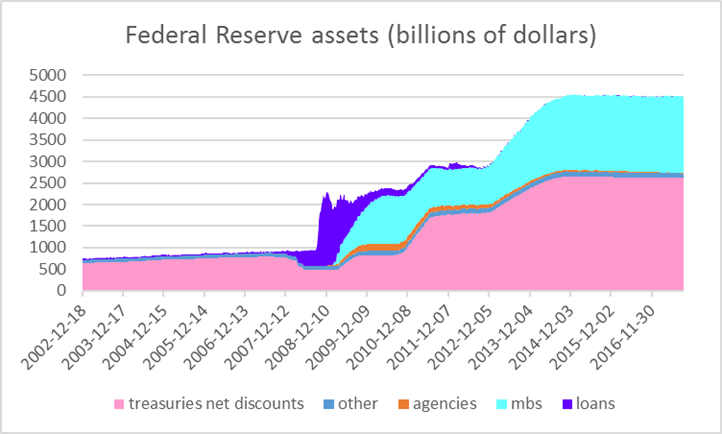

Historical Federal Reserve assets (Wed values, Dec 12, 2002 to Sep 13, 2017). Treasuries net discounts: U.S. Treasury securities held outright plus unamortized premiums on all securities held outright minus unamortized discounts on all securities held outright. Agencies: Federal agency debt securities held outright. MBS: Mortgage-backed securities held outright. Loans: sum of loans, net portfolio holdings of Commercial Paper Funding Facility LLC, Maiden Lane I, II, and III, net portfolio holdings of TALF LLC, repurchase agreements, preferred interests in AIA Aurora LLC and ALICO Holdings LLC, central bank liquidity swaps, and term auction credit. Other: sum of float, other Federal Reserve assets, foreign currency denominated assets, gold, Treasury currency, and special drawing rights. Data source: Federal Reserve H41 archive.

The Fed’s total assets have been steady at $4.5 T for the last three years, with 58% of its assets in U.S. Treasuries and 39% in mortgage-backed securities guaranteed by Fannie and Freddie. It kept the balance sheet steady by reinvesting those holdings whenever they matured. Beginning next month, the Fed will reinvest only some of its maturing securities, allowing its total holdings of both Treasuries and MBS to decline up to certain limits that the Fed spelled out in June. Under that schedule, Fed holdings of Treasuries would be at most $6 B lower by the end of October (a scant 0.2% reduction from current levels), while MBS would be at most $4 B lower. The pace would increase to $12 B and $8 B per month, respectively, in January, with additional accelerations in each quarter of 2018.

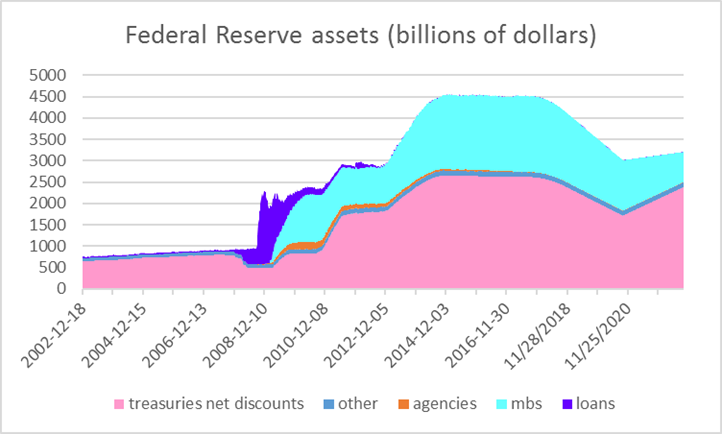

Historical Federal Reserve assets (Dec 12, 2002 to Sep 13, 2017) and projected (Sep 20, 2017 to Sep 28, 2022).

I’ve created a mock-up of what the balance sheet would look like if the Fed reduced its holdings by the maximal amount at a smooth weekly rate (for example, reduce its Treasuries by $1.38 B each week of 2017:Q4, by $2.76 B each week of 2018:Q1, and so on). I also suppose that the Fed maintains the rate achieved by the end of 2018 ($6.9 B per week for Treasuries) through 2019 and the first three quarters of 2020. But these projections assume the Fed will resume growing its balance sheet in 2020:Q4, and never let total assets fall below $3 T. My graph assumes (though the Fed has given no guidance on this) MBS continuing to decline at a $20 B monthly pace beyond 2020, but Treasuries start growing by more than $20 B in late 2020.

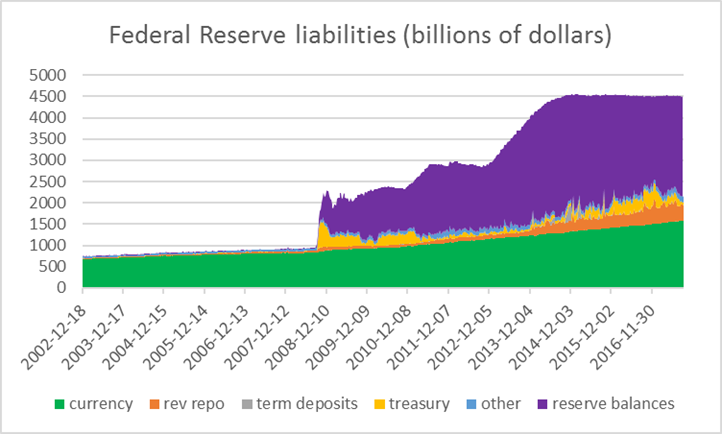

The reason the Fed may go back to growing its balance sheet within three years comes from thinking about the liability side of its balance sheet. The big bulge in assets has mainly been financed by extra Federal Reserve deposits held by financial institutions, shown in purple on the graph below. But several other liabilities are also significant– deposits held by the U.S. Treasury’s account with the Fed (yellow), deposits that get returned temporarily to the Fed through reverse repos (orange), and currency held by the public (green). A key feature of those last three is that under current Fed operating procedures these quantities are basically chosen outside the Fed. The Treasury calls the shots for how it manages its account, counterparties can essentially do as much or as little reverse repos as they wish at the rate offered by the Fed, and banks can turn their Fed deposits into cash whenever their customers want more dollar bills. Currency demand grows at a fairly steady, predictable rate, but the Treasury’s account and reverse repos are quite volatile. The reason that total liabilities have remained almost constant week-to-week for three years in the face of this volatility is that Fed deposits of financial institutions have acted as a big buffer, elastically growing or contracting in response to whatever happens at the Treasury or with reverse repos.

Historical Federal Reserve assets (Wed values, Dec 12, 2002 to Sep 13, 2017). Currency: currency in circulation. Rev repo: Reverse repurchase agreements (foreign official and international accounts plus others). Term deposits: term deposits held by depository institutions. Treasury: U.S. Treasury general account plus supplementary financing account. Other: Treasury cash holdings plus foreign official, service-related and other deposits plus other liabilities and capital. Reserve balances: reserve balances with Federal Reserve banks. Data source: Federal Reserve H41 archive.

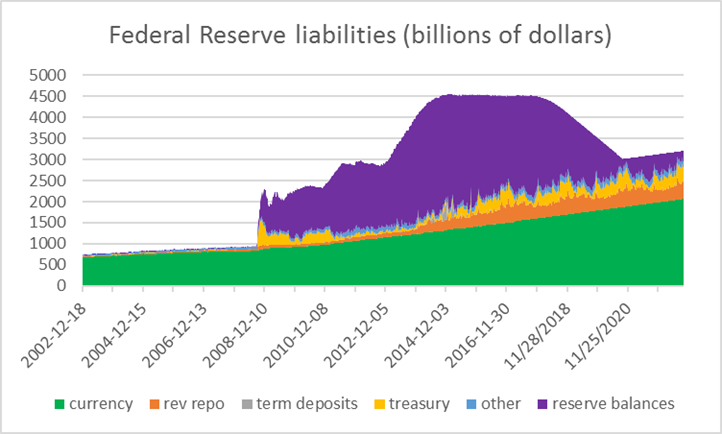

To get a visual picture of how Fed liabilities might evolve, I assumed that currency continues to grow at its recent historical pace. And to represent potential future volatility in the reverse repos and the Treasury’s balance, I simply assumed that the numbers for each of those series for Oct 2017 to Sep 2019 took exactly the same values they did for Oct 2015 to Sep 2017, and cycled through the same sequence again starting in Oct 2019.

Historical Federal Reserve liabilities (Dec 12, 2002 to Sep 13, 2017) and projected (Sep 20, 2017 to Sep 28, 2022).

The picture shows what would happen if the Fed were to continue reducing its balance sheet through the end of 2020. There would still be a very high level of Fed deposits by financial institutions on average by the end of 2020. But that’s not enough to cover the plausible variation in other Fed liabilities. For example, data from the New York Fed show that outstanding reverse repos went from $92 B on Nov 17, 2016 to $468 B on Dec 30. It takes a lot of reserves sloshing around the system to cover that kind of variation.

Of course, there are other changes the Fed may consider to its basic operating system, such as changing the way it conducts reverse repos, using temporary open-market operations to add or withdraw reserves as needed to offset changes in the Treasury balance, or moving to a true corridor system for controlling interest rates.

The gradual pace of contracting the balance sheet gives the Fed a couple of years to sort out how it’s going to do that.

Disclosure: None.

The fact that the Federal Reserve now is in our housing and MBS market is disgusting. If the economy collapses not only can they do little more given the low rates and inflated balance sheet, they will take losses in the housing market. Of course the argument s that they don't have to ever recognize markdowns, however, if they default or don't pay then they still must recognize the lack of interest payments. And them entering to dump bad loans and property direct into the market is frightening and will drive the market down further.

The Federal Reserve should have closed off this stain in the eye of capitalism with horrific potential consequences long ago.