Recovery Without Military Keynesianism

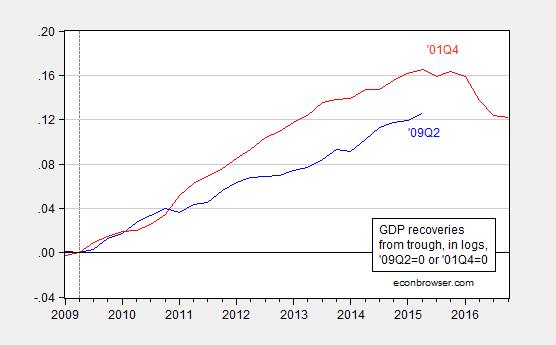

Thursday’s GDP release incorporated an annual data revision extending back to 2012. In this recovery, output is 4% lower (in log terms) than the corresponding point in the previous recovery. In Ch.2009$, 2015Q2 output was 92.9 billion lower (at quarterly rates). The comparison (in log levels, normalized to troughs) is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: GDP relative to 2009Q2 trough (blue), relative to 2001Q4 trough (red), in Ch2009$, in logs. A reading of 0.12 can be interpreted as meaning output was 12% higher than it was at NBER defined trough. Source: BEA, 2015Q2 advance release, NBER, and author’s calculations.

The gap falls to 2.9% when per capita GDP is compared.

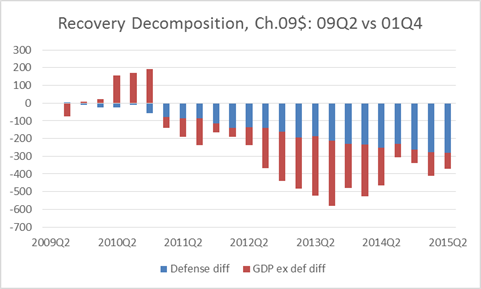

One interesting aspect of the slow recovery is the fact that government spending has been particularly low, as others have pointed out [1] (and contra common perceptions). Perhaps, more interesting is the source of the government spending that pushed output growth in the 2000’s: defense.

Figure 2: Contributions to differences in 2009Q2 and 2001Q4 recoveries, in billions of Ch.2009$, SAAR, from defense spending (blue) and all other spending (red). Source: BEA, 2015Q2 advance release, and author’s calculations.

In other words, most of the slower growth in an accounting sense can be attributed to lower defense spending. Does this mean we should embark upon another war? After all, the same voices who argued for invading Iraq have also argued for taking military action against Iran (e.g.., John Bolton). I do believe doing so would add to aggregate demand. Figure 3 (from this post) shows how much we spent up to FY2012 in real terms.

Figure 3: Cumulative real direct costs, in constant (FY2010) dollars by fiscal year, in the Iraq theater of operations (“Operation Iraqi Freedom”). Does not include debt service costs. Source: Nominal figures from Amy Belasco, “The Cost of Iraq, Afghanistan, and Other Global War on Terror Operations Since 9/11,” RL33110, Congressional Research Service, March 29, 2011, Table 3. Data for FY2011 is for continuing resolution, for 2012 is Administration FY2012 request. Deflated by CPI-all. CPI for 2011 assumes September 2011 m/m inflation is the same as August 2011 m/m inflation. Assumes 2012 inflation is equal to August 2011 CBO forecast for CY2012 inflation.

Figure 3 incorporates only direct fiscal costs to the United States government, and excludes interest costs. See here for another tabulation.

However, believe it or not, there are other ways of boosting aggregate demand, even when restricting oneself to spending on goods and services – and that’s spending on directly productive assets, such as infrastructure. To make this point concrete, note that in dollar terms, overall government spending more than accounts for the GDP differential. GDP was 371.7 Ch.09$ billion (SAAR) lower than the corresponding point in the previous recovery. Government spending on goods and services was 559.4 Ch.09$ billion less. As noted in this post, a big program of spending on infrastructure would clearly benefit the economy both on the supply and demand side. And yet, there is no evidence of movement here, particularly given the refusal of certain elements to consider more tax funding for such measures.[2]

Disclosure: None.

Interesting viewpoint. But surely, building roads and fixing bridges, as you point out on page 2, would add to aggregate demand and be useful in saving man hours and boost productivity as well. If we need to spend to get the economy going, it should be domestically and you clearly agree that is a way out, a sensible one.

We already lap other nations in defense spending many times over.

To go to war for the economy when there are other ways of improving the economy is just wrong, dangerous, and less efficient than building at home. I believe there are economists and politicians who would make decisions for war, factoring in the economy, but going to war with Iran could create a nuclear war, and it is hard to trade stocks and build houses when nukes are crossing continents!