A Tax Exemption Has Helped Credit Unions Since The 1930s, But Some Argue They Should Be Treated More Like Banks

from the Richmond Fed

-- this post authored by Sabrina R. Pellerin

The first U.S. credit union - St. Mary's Cooperative Credit Association in Manchester, N.H. - opened its doors in 1908 with the mission of meeting the personal financial needs of a targeted community: French-American mill workers. Those who helped organize St. Mary's believed that access to credit for poor working families would improve their well-being. Today, this same credit union is a full-service financial institution, renamed St. Mary's Bank, and is open to anyone willing to purchase one share of "capital stock" for $5. The evolution of St. Mary's resembles that of the entire credit union industry with the expansion in both its membership base and its services.

Unlike banks, which operate to maximize stockholder wealth, credit unions are owned by their members, or depositors, and are therefore considered to be cooperatives. Membership in a credit union is limited to individuals who are part of a well-defined community or share a "common bond," such as the mill workers at St. Mary's. Common bonds can be based on employer, membership in an organization, or residence within a well-defined geographic area. For example, HopeSouth Federal Credit Union restricts membership to persons who "live, work, worship or attend school" in Abbeville County, S.C. Each credit union is required to define the specific common bond that establishes the "field of membership" from which it can draw its members.

As is typical of cooperatives, credit unions are structured as nonprofits and are democratically owned and operated with each member having one vote regardless of the amount of deposits held. Moreover, members elect unpaid officers and directors from within the credit union's field of membership. As of December 2016, there were approximately 5,919 credit unions operating in the United States (compared to 5,198 commercial banks) serving 109.2 million members. While large in number, their combined assets of $1.3 trillion are less than the asset holdings of any one of the top four commercial banks.

Some observers find that credit unions today are largely indistinguishable from banks, while others believe that their structure and member-driven community focus makes them unique. Unlike banks, federal and state credit unions have been exempt from paying federal corporate income taxes since 1937 and 1951, respectively.

Critics of the tax exemption say that a series of relaxed rules over the decades have allowed for direct competition between banks and credit unions, and they argue it has created an unfair and artificial competitive advantage for credit unions.

While the debate has been raging for decades, in the last year, the agency responsible for overseeing credit unions, the National Credit Union Administration (NCUA), proposed and implemented further relaxations of some of its restrictions on credit unions' member business lending and fields of membership. These restrictions are unique to the credit union industry, and the rule relaxations were met with opposition by bank advocacy groups and other observers who claim the changes expand the field in which credit unions can apply their cost advantage. According to the NCUA, these rules enhance credit unions' ability to meet the demands of an evolving financial services industry and remove unnecessary impediments to credit union growth. It's the latest chapter in a long-standing and sometimes acrimonious debate.

Credit Unions Then and Now

Credit unions arose as a solution to meeting consumers' demands for credit at an affordable cost - particularly for individuals who did not have established credit. To substitute for collateral, credit unions leveraged social connections among a community of members. Specifically, their distinct niche was extending small-value, unsecured consumer loans to members who shared a common bond.

With a cooperative structure, members of early credit unions had something to lose (reduced earnings or loss of deposits) if a fellow member failed to repay on a loan and thus had an incentive to monitor the character and economic prospects of one another to determine a borrower's creditworthiness. Moreover, the community ties led to social pressure for repayment, lowering the probability of defaults on loans.

While many cooperative features of credit unions remain intact, credit unions have changed dramatically since the early 20th century. For instance, in 1970, the Federal Credit Union Act was amended to create a regulator to oversee federal credit unions - the NCUA - and extended deposit insurance protection to credit union members through the creation of a new insurance fund (similar to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, created for commercial banks nearly 40 years prior). With the advent of deposit insurance, credit union savers no longer had a strong incentive to monitor or apply social pressure to credit union borrowers because their investments were protected by the insurance fund, increasing the similarities between banks and credit unions.

The business of consumer lending has changed drastically as well. Starting with the introduction of FICO scores in 1989, financial institutions could consider credit scores when deciding whether to extend a loan. This financial sector innovation diminished, to some extent, the importance of relying on social bonds to assess creditworthiness.

Furthermore, technological changes and increased competition have made it much easier for consumers to gain access to financial services. For instance, credit cards have increasingly become a substitute for the small-value consumer loans that credit unions have historically specialized in. According to John Tatom of Johns Hopkins University, an economist and tax expert, people who use credit unions are not as unique as they once were because they now have access to a wider range of financial services and providers. Tatom says that times were very different in the early 20th century when credit unions were first gaining popularity, noting that people who were going to credit unions then "were people who really did not have as much access to the financial system. Banks didn't want their business - they couldn't as readily use bank deposit facilities or get bank loans."

Why the Tax Exemption?

Despite criticism that regulatory relaxations have made credit unions more bank-like, the historical rationale for the exemption does not appear to have been tethered to credit unions' lending or field of membership restrictions. The two legislative justifications for the tax exemption - which have remained substantially the same over the last 100 years - are the mutual structure of credit unions and their purpose of assisting those of modest means.

The first credit union tax exemption occurred in 1917, when U.S. Attorney General Thomas Watt Gregory concluded that the 1916 Revenue Act, which exempted mutual savings banks and cooperative banks from federal income tax, applied to state credit unions chartered in Massachusetts. This interpretation was based on his view that credit unions were "substantially identical" to cooperative banks and other mutually owned banking organizations, which were already tax-exempt at the time. Based on the attorney general's statement, equal tax treatment of credit unions and other mutually owned banking organizations was warranted because both were mutually organized and had the purpose of assisting "those in need of financial help whose credit may not be established at larger banks."

In the 1998 Credit Union Membership Access Act, Congress reiterated that credit unions are exempt from federal income tax "because they are member-owned, democratically operated, not-for-profit organizations generally managed by volunteer boards of directors and because they have the specified mission of meeting the credit and savings needs of consumers, especially persons of modest means." Today, the Federal Credit Union Act still states that its purpose is to "make more available to people of small means credit for provident purposes through a national system of cooperative credit."

Flown the Co-op?

The Internal Revenue Code provides some basis for credit unions' special tax treatment by virtue of their cooperative nature. According to the code, any corporation (with some exceptions) operating on a cooperative basis is eligible for favorable income tax treatment that is similar to that afforded to credit unions. While other cooperative financial institutions, such as mutual savings banks, still receive some favorable tax treatment, their full exemption from federal income tax was repealed with the Revenue Act of 1951.

Critics of the credit union tax exemption have long used the repeal of the mutual savings bank tax exemption as evidence that credit unions should lose theirs. Because the credit union tax exemption seemed to rely directly on a principle of establishing parity between credit unions and other mutually owned financial institutions, it might seem logical for the repeal of the tax exemption for mutual savings banks to have been followed by a repeal of the tax exemption for credit unions. But credit unions were specifically exempted from the repeal.

One factor that could explain the retention of the credit union exemption is that mutual savings banks were accused of no longer being "self-contained cooperative organizations." In fact, there did not appear to be a requirement for mutual savings banks to restrict loans only to depositors or members, which is still required of most credit unions today. Therefore, while there may be many similarities between mutual savings banks and credit unions, credit unions arguably retained more of the cooperative qualities. Furthermore, the repeal of the tax exemption for other mutual financial institutions may have been more practical than ideological. In her 2001 book Politics and Banking: Ideas, Public Policy, and the Creation of Financial Institutions, Susan Hoffman posited that mutual savings bank taxation may have been the result of a strong bank lobby and a need to raise funds for the Korean War.

Where Does the Credit Union Subsidy Go?

Estimates of the lost government revenues resulting from the credit union tax exemption vary based on the source and underlying assumptions but range from approximately $500 million per year to more than $2 billion per year. The credit union tax exemption is an example of a government subsidy. Such subsidies are generally provided to encourage greater production of something viewed as societally valuable. For example, in the case of credit unions, it was - and still is - perceived by many observers that too few low-to-moderate income individuals were able to access financial services at affordable rates.

The public policy rationale for the tax subsidy has relied on credit unions' not-for-profit cooperative structure and their focus on providing financial services to individuals of modest means. If the subsidy is flowing to the targeted beneficiaries, then the public policy goal is achieved. The intended public benefit could take the form of lower borrowing costs for low-income individuals that would then free funds for other essentials or provide credit to those who otherwise would be unable to borrow. On the other hand, a subsidy can also be wasted if it's not flowing to those for whom it is intended and distortionary if it's diverting capital away from its best, most highly valued use.

To assess the extent to which tax policies achieve their intended outcomes, economists study tax incidence - the analysis of who bears the burden of a tax, or in this case, who benefits from a tax-based subsidy. Determining who wins and who loses from a tax subsidy is not entirely straightforward, however. It depends on the degree of competitive pressure (the availability of substitutes in the financial market) and consumers' sensitivity to fluctuations in prices and interest rates.

Since credit union members are also the owners, unlike banks that have stockholders, credit union net income can be retained to build capital or it can be distributed to members in the form of higher interest rates on deposits, lower loan rates, or enhanced customer service. Academic studies examining the tax incidence have largely focused on whether credit unions pay higher interest rates and charge lower loan rates than banks operating nearby, but some studies have also examined whether the subsidy is inefficiently flowing to credit union managers and workers (in the form of higher wages) - or being used to absorb losses from risk-taking or mismanagement - rather than flowing to members.

A 2016 working paper by Robert DeYoung of the University of Kansas and several co-authors compared a sample of credit unions to comparable banks and found that three-quarters of the subsidy is passed on to credit union members in the form of higher deposit rates. Although the entire subsidy is not flowing to members, this finding that credit unions offer above-market deposit rates provides support for one justification for the tax exemption, namely, that the cooperative structure results in benefits to members.

Mission Accomplished?

While the credit union subsidy appears to be flowing to members, the other justification for the tax exemption is that credit unions especially target those of modest means. A problem in determining the extent to which credit unions serve individuals of "modest means" is that no credit union legislation explicitly defines that term. Interpretations have ranged from individuals in poverty to those in the middle class. Regardless of how researchers interpret the concept of modest means, however, the majority of studies that have been conducted suggest that credit unions are in fact less likely than banks to serve this subset of members. For instance, results of a 2002 national member survey conducted by the Credit Union National Association (CUNA), a trade association of credit unions, revealed that the average household income of credit union members exceeds that of nonmembers by 20 percent. Furthermore, results from the Federal Reserve's 2004 Survey of Consumer Finances indicate that 31 percent of credit union members were low-to-moderate income individuals compared to 41 percent at commercial banks. Moreover, according to a 2009 study by William Kelly Jr., then of Grinnell College, 89 percent of the benefits that flow to members in the form of lower loan rates and higher deposit rates are going to middle- and upper-class consumers. He argued that this unintended consequence of the subsidy is based on the fact that the benefits are proportional to the size of the loans and deposits, leading to greater benefits to affluent households.

On the other hand, researchers Jim DiSalvo and Ryan Johnston of the Philadelphia Fed found in a 2017 study that credit unions lend to a slightly larger portion of low- and moderate-income tracts than do small banks, but they also found that credit unions reject more home loan applications from low-to-moderate income members than small banks.

Although research findings are mixed, credit union proponents contend that they have stayed true to meeting their mission of serving people of modest means. They argue that while they provide services to consumers at all levels of income, they serve low- and middle-income consumers by offering more affordable rates and lower fees than banks along with providing financial literacy education. For example, findings from a 2016 report by CUNA indicated that the fees credit unions collect on low-balance accounts are less than a third of what banks charge on low-balance accounts.

Staying on Target

The structure of the credit union industry itself could be at odds with its mission to help those of modest means due to selection bias. For example, many credit unions have common bonds that restrict membership to only their occupational group, which means that their members may be more likely to be employed full time. In responding to why banks might serve relatively more people of modest means, John Radebaugh, president of the Carolinas Credit Union League, acknowledged that occupational credit unions with restricted memberships "can skew the results, but over half of our credit unions in the Carolinas have a low-income designation. "Low-income designated credit unions focus on serving populations with limited access to "safe financial services," the majority of whom meet specific income-level criteria. Nationwide, 42 percent of all credit unions are designated low-income credit unions.

Although bank groups have criticized credit unions for trying to expand their field of membership, credit unions assert that doing so could actually help them advance their mission of serving those of modest means. But this has been disputed: A study by economist and consultant Kay Plantes, commissioned by the Wisconsin Bankers Association, suggests that removal of the common bond or field of membership restrictions would not necessarily lead credit unions to serve more low-to-moderate income members. Plantes examined large credit unions with broad fields of membership in Wisconsin to identify whether credit unions with fewer member-base restrictions were more likely to serve those of modest means. Plantes found that large credit unions were targeting wealthier customers, as evidenced by the markets in which they locate branches and the income level of mortgage borrowers.

One way to ensure that credit unions with large fields of membership are in fact serving low-to-moderate income people, to at least the same extent as banks, would be to subject them to the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA), a law that encourages banks to lend to low- and moderate-income communities. In a study by the National Community Reinvestment Coalition (NCRC) of credit unions in Massachusetts and Connecticut - where large state-chartered credit unions are required to adhere to CRA requirements - the NCRC found that CRA-covered state-chartered credit unions outperform CRA-exempt federally chartered credit unions on fair lending indicators.

Moreover, Kelly concluded in his 2009 study that the tax code could be modified to better serve people of modest means by withdrawing the tax exemption in combination with providing credit unions with "tax credits that could offset the tax and leave the full subsidy, depending on how well a credit union carries out its mission." The effect of this, he wrote, would be equivalent to keeping the full subsidy in place for "the many credit unions whose work in serving especially people of modest income is exemplary."

Does Size Matter?

In a 2006 report, the U.S. Government Accountability Office noted that while large credit unions are few in number, they are "responsible for a disproportionate amount of the potential tax revenue as compared with small credit unions." According to a 2004 study performed by Chmura Economics & Analytics, 84 percent of the government's loss of tax revenues could be eliminated if only credit unions with assets below $500 million were exempt.

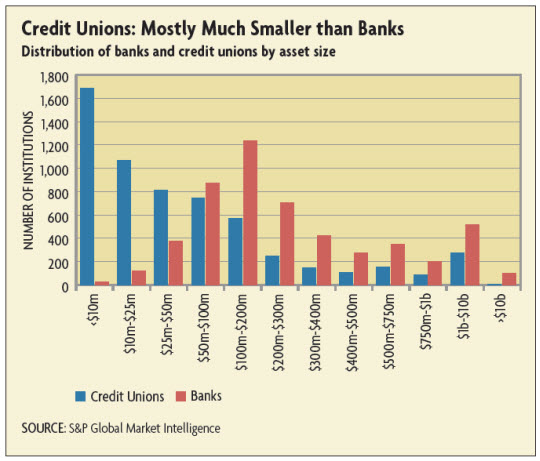

Although observers opposed to the tax advantage argue that credit unions have become more bank-like in their product and service offerings, most of the credit union industry still looks very different from the banking industry. One unique feature of the credit union industry that remains starkly different from the commercial banking industry is the sheer number of very small institutions. The vast majority - 73 percent - of credit unions has assets less than $100 million and more than a quarter have assets less than $10 million. (See chart.) In contrast, only 28 percent of commercial banks have assets of less than $100 million and only a handful have assets less than $10 million. Most associational credit unions - such as those run out of churches, schools, or fraternal associations - fall into the less than $10 million category. Credit unions are also much less concentrated than banks with the top 10 credit unions controlling 16 percent of total credit union industry assets compared to the top 10 banks that control 55 percent of total banking assets. The size of an average credit union at the end of 2015 was $199 million compared to $444 million for an average small bank (not in the top 100 by assets). Credit unions do appear to be growing at a faster rate than banks, both large and small - but they still only hold 7 percent of all depository institution assets (including credit unions, commercial banks, and thrifts).

(Click on image to enlarge)

Furthermore, some studies have found evidence that larger credit unions may be competing more with banks compared to the smaller credit unions. For instance, the 2004 Chmura study found that less than half of credit unions with under $10 million in assets offer typical banking products and services such as debit cards, Roth IRAs, or first mortgages - services that more than 90 percent of credit unions with more than $100 million in assets offer their members. Additionally, larger credit unions are more likely to offer larger loans compared to loans extended by small credit unions.

On the other hand, the subsidy and its intended purpose of serving individuals of modest means could explain why there are so many small credit unions in an industry with high fixed costs. For instance, the subsidy might be allowing a credit union to operate in an otherwise unprofitable market. If the subsidy allows for the availability of credit where it would have otherwise been absent, even if the credit union is not offering higher deposit rates or lower loan rates than an average bank, it could provide the financing for, say, a low-income individual to buy a car to get to work or establish a source of credit in a rural area where a bank might not find it profitable to operate.

The research performed on credit unions and the tax exemption reveals mixed results as to whether, on the whole, credit unions still serve the same purposes today as they did when they were first chartered in the early 20th century. The features that have historically been characteristic of credit unions, such as the common bond, have arguably become outdated with innovations such as deposit insurance and credit-rating agencies. Critics of the tax exemption cite this as evidence that credit unions have become less distinguishable from banks and therefore no longer warrant special tax treatment. Credit union proponents contend that characteristics, such as the common bond, were merely incidental to safe and sound credit union operation at the time and not necessarily the core mission of the industry, which is to operate a cooperatively owned financial institution that serves its members, especially those of modest means.

Disclaimer: No content is to be construed as investment advise and all content is provided for informational purposes only. The reader is solely responsible for determining whether any ...

more

Poor poor banks. Credit unions eating your lunch? You don't lend much anyway, so credit unions are important to many Americans. Can't say that about banks.