Curse Of The Zombie Junk

If the road to Hell is paved with good intentions, in economic terms the paving is done by zombies. We’ve all heard of the convention regarding Japanification. In desperation trying to avoid a worse fate, many of Japan’s tortured financial institutions were left open and operating so as to not force losses too much at a time. Rather than allow for recovery, these zombie banks locked Japan’s economy into its so-called deflationary mindset from which it has yet to escape almost three decades later.

Zombie banks were not the only undead firms in Japan’s lasting fall. These eventually gave way to a proliferation of zombie firms, largely industrial, who made up the vast majority of that country’s NPL problem lingering well into the 21st century. Firms that creative destruction would have destroyed long ago were purposefully propped up often on official approval simply because central bankers fear 1929 as if that is the only route to long-lasting depression.

Just as the global economy has exhibited the same symptoms as Japan’s did in the nineties, starting with one lost decade for it already, several OECD researchers last year raised the zombie issue in the non-financial context (at least with regard to Europe).

Policies that spur more efficient corporate restructuring can revive productivity growth by targeting three inter-related sources of labour productivity weakness: the survival of “zombie” firms (low productivity firms that would typically exit in a competitive market), capital misallocation and stalling technological diffusion…As the zombie firm problem may partly stem from bank forbearance, complementary reforms to insolvency regimes are essential to ensure that a more aggressive policy to resolve non-performing loans is effective.

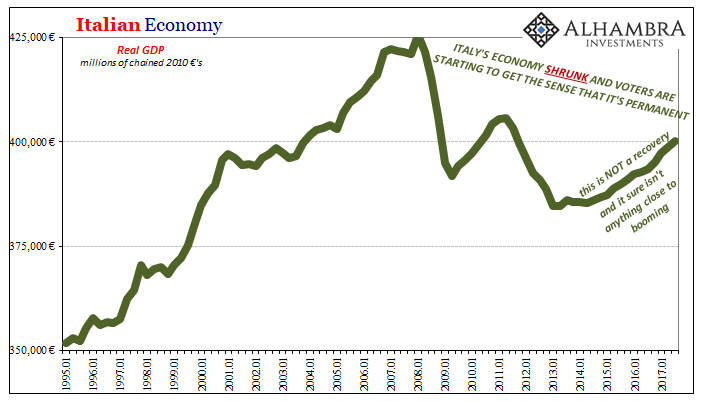

In places like Italy where Italian banks are bursting with NPL’s, there is an obvious link between them and Italy’s descent into further upheaval.

But this may not strictly be a European problem, either. Could it be that it hasn’t been just banks willing to yield forbearance?

You can understand the reluctance to force liquidation on an NPL from the perspective of a troubled bank; the company goes away and the bank immediately books the loss. If the zombie firm remains open even if economically unproductive, creative mathematics on the bank’s balance sheet can maintain a partial illusion indefinitely (as we’ve seen from Japan’s experience) with quasi-official approval. If that NPL can just hang on a little bit more, economic recovery is surely coming and it will fix everything.

It’s an understandable if still lamentable self-delusion. I don’t believe it has been limited to just the financial sector nor constrained by geography.

What I mean by that is specifically US corporate junk (and a lot of other global junk brought on in the 2000’s by the eurodollar’s advance). Junk debt was pummeled to a crisis degree starting in late 2014. For almost two years, the selloff was steep and relentless. Some of that related to oil prices, since a good deal of especially leveraged loan volume derived from US shale, but the whole space went from the place to be to the place to kill your portfolio.

Despite the degree of price pain, however, there really wasn’t many defaults. Overall, it amounted more to a credit crunch, difficulties for a time where junk credits couldn’t issue new debt. In times past, a credit crunch was the precondition for the wave of defaults. In 2014-16, there was surely fear of them that never materialized.

Rather than breathe a full sigh of relief, the junk market rebounded but quite clearly remains still on edge now more than two years after that prior bottom. Why?

I think the answer is zombies. Default risk didn’t really diminish even if the “rising dollar’s” negative influence on liquidity and economy oeventually did. The weakest junk credits were given a temporary reprieve, but the hangman of liquidation and bankruptcy still looms. Many firms, it may be, were given the same kind of forbearance that Japanese zombie banks once provided Japanese zombie industrials (or European banks routinely deliver to European zombies) – only this time it was the junk market.

The idea appears to be generally the same – give the zombies in junk enough time to survive until economic recovery. Rather than book any big losses in 2015 and 2016, if they could hang on until 2017 then the big economic boom being predicted would pay off especially for where junk prices had been at the lows. No need to force (particularly in leveraged loans) any bankruptcy hits because in recovery everything would be fixed.

But that was supposed to be 2017; it didn’t happen. Fundamentally, zombie junk remains as it was two years ago simply because the economy does, too. The bankruptcy wave never materialized back then but ostensibly there are still really only two outcomes; either recovery, or credit/default risk.

As we move further into 2018 without the economic acceleration and boom (hysteria aside, the inflation scenario never got very far in junk markets), and with liquidity risk rising again, it can’t be surprising that junk markets struggle.

This is a problem for more than the US corporate bond sector. Risk behavior tends to be clumpy in that respect, particularly if there is a high degree of money irregularity behind it.

Disclosure: None.

Good article. Sadly this junk is still floating and no one is watching what will happen if it ever sinks back down into default territory.