What We Are After

I am a long-term optimist by nature. Stop laughing. I am well aware I have attained a reputation as something of a permabear, but that is merely the consequence of the time period in which we inhabit. Read some of the things I wrote in 2009 (and even in early 2010) and you might think them authored by an entirely different person. If there is reason to be optimistic about the intermediate term, I will be so.

My role at Alhambra in research is to present the unvarnished truth, as much as may be discerned by any single person. It requires a straightforward assessment of the world around us, meaning that it can’t be couched in rigid terms describing better the past. We invest with risks in mind, and if you can’t be honest about the world then you won’t have sufficient idea of the risks.

A good part of that process is appreciating clear distinctions for what they are, free from rationalizations tied to, frankly, dogma. What does the negative premiums of yen-dollar cross currency basis swaps have to do with a working mother in her 40’s trying to one day retire with some stock wealth? Quite a bit actually, though it is often obscured in a haze of complexities and seeming contradictions how one might come to affect the other.

To put it in very general terms, the world has changed. The baseline behind everything has shifted so that a cross currency basis swap or an overnight SHIBOR rate doesn’t describe a foreign market so much as how the world we all share now isn’t close to the same anymore. So long as these things continue to be different, so we have to keep in mind the implications of a different framework.

Earlier this year it was fashionable (once again) to invoke the bond market “massacre” of 1994. Global sovereigns last summer traded so low and flat that they practically dared the mainstream to make the comparison. Many did:

Paul Schmelzing, a PhD candidate at Harvard University and a visiting scholar at the Bank of England, said if the latest bond market bubble bursts, it will be worse than in 1994 when global government bonds suffered the biggest annual loss on record.

When asked on CNBC whether his fund was short bonds, famed permabull David Tepper bellowed, “you bet your heinie.” All the ingredients seemed to be there. The Fed was going to raise rates; inflation was sure to pick up as the unemployment crept lower and lower; and though Trump has endured political scorn in constant fashion, earlier this year there was a time when his agenda seemed to be a breath of fresh air amidst the smoking wreckage of QE’s, ZIRP’s, and central bankers.

Yet it was all smoke and mirrors, a sleight of hand magic trick that wasn’t the least bit magical and not really much of a trick. The mainstream has lost all perspective because ten years after the beginnings of the Great “Recession” it doesn’t seem believable that normal isn’t possible. Most commentary starts with the basic premise that it is.

(Click on image to enlarge)

Just looking at the bond curves from 1994 should have disabused any such notions. They are nothing like anything we can find today. That’s not some trick of mathematics, nor is it the genius of Ben Bernanke. The distance between those of two decades ago and what we find all around the globe today is a meaningful distinction played out in credit.

It’s as much about behavior as it is the CPI or GDP calculations. In 1992, for example, Warren Buffet had to bail out, essentially, Salomon Brothers for reasons that couldn’t at the time be adequately explained. What I mean is that it was well-understood why Buffet was taking over the investment bank, but not so much why Solly got itself into trouble in the first place.

A seemingly rogue bond trader had been openly and recklessly violating Treasury rules about bidding at auctions. Paul Mozer had been placing improper trades in an increasingly brazen effort to corner the market on OTR UST’s. The LA Times, unable to appreciate what Mozer was up to, called it contemporarily his “inept little scam” that made the bank just a few million dollars while imperiling its very existence.

The Treasury Department in its joint report with the SEC and other agencies uncovered widespread fraud at MBS auctions, too. Paper floated by GSE’s was oversubscribed by practically everyone using any means possible, including many broker-dealers who would even resort to keeping two sets of books. As I wrote a couple years ago recounting the episode in detail:

In other words, it was only being closed-minded about what was taking place in “money” that hid what Mozer and so many others were up to – collateral had become currency, maybe even at that early date the currency, and had thus attained “value” far beyond what was thought to be an “inept little scam.” Rehypothecation and leverage, and the legal and accounting structures surrounding and abiding them, made that so.

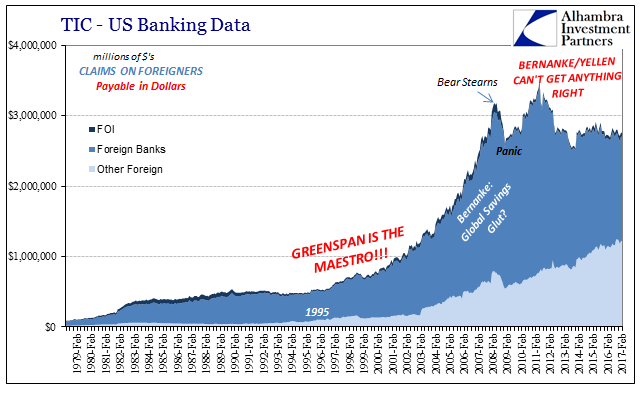

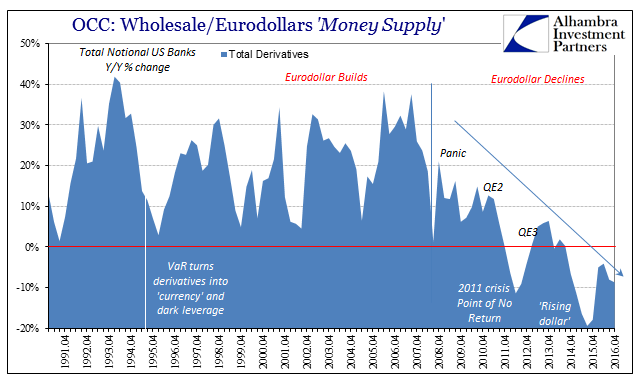

The conditions of 1994 were that system, where risk was everything as the eurodollar system rapidly built itself up into a parallel world traditional thinking couldn’t often comprehend. Policymakers by that time had even stopped trying; no longer would central banks concern themselves with money supply, instead they had long before shifted focus exclusively to “money demand” and seek its control with nothing but the federal funds rate (in US dollars).

Even the famous October 1994 Fortune article that mainstreamed the “massacre” label inside of it describes as its basis this same breathtaking change:

The bond business isn’t just bigger. It has also become mystifyingly complex as Wall Street’s financial wizards use high-powered technology, even an occasional Cray supercomputer, to devise new ways to hedge risks or speculate on minute changes in interest rates. The growth of financial derivatives, which basically are side bets on the future course of interest rates, exchange rates, and commodities prices, has not only magnified the financial consequences of a market move but also thwarted traditional analysis of interest rate movements, which tends to focus more on economics than on internal market dynamics. Combine these recent developments with the new technological capability to hurl billions of investment dollars across oceans electronically, and you suddenly have a global bazaar where events in Chiapas, Mexico, can lead to huge gains or losses in New York, London, and Frankfurt.

Bonds sold off not because Alan Greenspan commanded them, but rather because everything was changing on a wave of monetary expansion that wouldn’t crest (no matter what) for thirteen more years. It was very easy to be optimistic, thus a bond bear, under those circumstances. They just don’t any longer exist. Those days of big risks and even bigger payoffs (in money dealing) are long gone.

(Click on image to enlarge)

On top (blue curves) is what you expect to find when things are moving forward and upward, even if you don’t know exactly why they always seem to go in that direction; what’s below (red curves) is what you expect to find when things aren’t moving at all despite everything that has been done to change that.

(Click on image to enlarge)

(Click on image to enlarge)

I am, again, a long-term optimist by nature. I expect fully that the global economy will become unleashed and that when it does throw off the monetary anchor it will be a very, very bad time to be a bond investor. The negative part, the permabear part, is that the monetary system has to legitimately and meaningfully change first. After ten years, it isn’t even close. In many ways, we remain stuck on Step 1, which is merely explaining and identifying the problem.

Cross currency basis swaps shouldn’t really matter, but that is why they do. It’s not for trivial pursuits of vain intellectual stimulation, the unraveling of great mysteries and placing impossibly hard puzzle pieces together for the sake of doing so. We have to understand this world as it is, not as it was.

Disclosure: This material has been distributed fo or informational purposes only. It is the opinion of the author and should not be considered as investment advice or a recommendation of any ...

more