There’s A Lot Of Relevant History In Going To The Bond Market

For Ben Bernanke, characterizing a successful tenure is exceedingly hard. Afterward writing a memoir about his time at the Fed, however, made such a task a necessary one. Given so few options from which to define his legacy, the former Chairman decided very carefully about how to frame his efforts. And still all he could come up with was a version of “jobs saved.”

In early October 2015, coinciding with his book tour, Bernanke was given space in the Wall Street Journal to write another op-ed this time under the banner How the Fed Saved the Economy. Given the economy as it was, his standard for judging monetary policies would have to be carefully nurtured. He was among the first to declare the “2 and 5” point, the Phillips Curve embodiment of orthodox thinking where the most any central bank can do is to elicit stable inflation (in the form its inflation target) while at “full employment.” Having “achieved” 5% unemployment and no runaway inflation above 2%, as he said, “the central bank did its job.”

Forgive the rest of us if we don’t agree. When starting out in 2008 with so many monetary experiments running concurrently, the idea of 2 and 5 was drastically different than what we have now, but at that time in every the same as it had always been before. Recognizing the massive and obvious disparity for the recovery that was promised and the “recovery” that was “achieved”, his answer in order to frame his efforts in the best possible way was to say, essentially, “at least it wasn’t worse.”

To do so, Bernanke pointed to Europe. When he wrote that article back in October 2015, European GDP had just about pulled even with the precrisis period. US GDP had by that time already surpassed the pre-crisis peak and was almost 9% above it. To Bernanke, this was due entirely to his “courage” at the Fed, for the ECB had been, in his judgment, slow to react with the big guns. With all that has happened in the year and a quarter since he made the claim, I wonder how a similar article might be written today after full-blown QE in Europe achieved the same paltry results.

Even then, however, his claims were dubious if not completely disingenuous. To start with, 9% GDP expansion peak to peak might sound significant, but it is instead a mark of total failure. As I wrote at the time, “What he neglects to mention is the 31 quarters it took to find even that level.” In the same amount of time following the severe 1974-75 recession, US GDP in real terms had advanced some 22%, and that was during the worst part of what is now forever known derisively as the Great Inflation. Bernanke’s economy couldn’t even register half the growth of an age that is universally agreed to be a prime example of a central bank not doing its job – and not even knowing what its job actually was.

From that perspective, there wasn’t and still isn’t a whole lot of difference between the US and Europe, as political situations in both places over the past year further align in recognition of that fact. What difference there has been, however, is easily explained in a way that is only related in further failure of Bernanke’s “courage.” Unlike the US, Europe doesn’t have now and didn’t then a robust bond market alternative. The continent is highly, hugely dependent on banking (really “banking”) in a way that the US has never been. This isn’t to say that wholesale banking wasn’t the basis for the US version of the system, not at all. But in the immediate aftermath of crisis the US economy had the bond market to turn to in a scale that Europe did not, which was especially problematic in 2011 and 2012.

The whole global economy turned lower in 2012 in synchronized fashion, but Europe got it the worst. To Bernanke, that was QE (as a second, third, and fourth application in the US to where the ECB hadn’t even started); with QE now pretty much accepted as having little effect anywhere, the fact that especially US companies could continuously borrow via bonds rather than financially through “dollars” was a major difference. In the end, obviously, it wasn’t enough of one except as that small matter of degree (neither the US or Europe experienced recovery, only variable definitions of its absence).

It may be surprising in the mainstream, but this separate condition is one that was discussed in some great detail in the late 1990’s and early 2000’s in relation to Japan. Like Europe, Japan was almost entirely dependent upon banking (really “banking”) with almost no bond market to speak of (beyond, of course, JGB’s). Thus, when banking is the central area of dysfunction, there are no alternatives for a monetary scheme derived from it (credit-based money). One of the earliest reforms undertaken in Japan was the Financial System Reform Act which became effective in April 1993, finally allowing Japanese banks, through securities firms subsidiaries, to enter the underwriting and securities business in order to open it up.

With almost a quarter century of Japan still stuck in a lost decade (words have little meaning in these economic contexts anymore, one of Bernanke’s true contributions), obviously, like the US economy, a bond market doesn’t make enough of a difference. Instead, what is important is to realize that by emphasizing the bond market in various ways as an alternative to bank-drawn credit or money (the distinction between credit and money in a credit-based monetary system being clearly blurred) these various places and conditions merely help identify the problem if not so much the solution. Having a bond market helps, but it isn’t the answer.

That is especially true in the context of the eurodollar system. Banks create and destroy “dollars”, whereas the bond market trades mostly in dollars. Therefore, the bond market can only ever be a partial substitute no matter how large the potential size and depth of it. I will (and have) argue that is why in the overall context the US economy truly didn’t outperform Europe’s to any meaningful degree.

This contrast, however, is not a matter of purely historical debate. It is, as we see continuously, ongoing. Yesterday, Reuters reported (big thanks to Jason Fraser of Ceredex Value Advisors for spotting this) that the PBOC has started to encourage Chinese banks to issue more offshore bonds denominated in dollars. For the mainstream, this is a huge surprise and a confusing one; from the perspective of the ailing eurodollar system, it is merely the latest step in escalating desperation whereby the Chinese central bank cannot solve a monetary puzzle the mainstream doesn’t even consider as possible.

From the article:

Financial institutions already account for around half of new US dollar bond issues in China. While the PBoC has not explained its reasons, market participants think it aims to curb renminbi depreciation by keeping US dollar outflows within the Chinese financial system. Mainland banks will be able to onlend the proceeds to corporate clients, while dollar issuance will also offer Chinese investors an alternative to buying wholly foreign securities.

That paragraph is everything that is wrong with commentary and mainstream analysis, if only because it adheres to the traditional view of money and global currency. Like everyone else, China’s corporate sector is “short” “dollars”, a fact that at least makes its way into this article. The next step is to connect to very closely spaced dots that aren’t even intuitive leaps, yet are made so because by orthodox dogma the Fed has “printed money” via QE’s and therefore dollars should be, and can only be, plentiful. Given dutiful attention to that assumption, the only explanation Reuters can provide in order to explain why the PBOC might be boosting a bond market solution in China bank dollars is “to curb renminbi depreciation.”

And that is tantalizingly close to the actual problem, as CNY “depreciation” is very closely linked within this whole “dollar shortage” paradigm. If the eurodollar is bank balance sheet capacity in all its various forms, then the “dollar” shortage” or “rising dollar” is the incapacity of global banks to provide them, further causing various local disturbances defined as “dollar” borrowers having to pay up for them (in various ways, which in the end works out to a falling local currency). There is only one currency war, as I explained just a few days after the supposedly shocking PBOC “devaluation” in mid-August 2015:

In short, the actions of the PBOC, seen in light of what was a convertibility mini-crisis, a “run” of sorts, make sense where the yuan fix as some kind of “stimulus” in devaluation does not (or is at least far too inconsistent to be explanatory). The PBOC held the yuan steady to a near plateau for five months hoping for cessation of “dollar” pressure, but, like a coiled spring, it only intensified until there was no holding back anymore.

The key about the fix is China’s banking and the “dollar” short; to hold the yuan steady under “dollar” pressure meant something was supplying “dollars” somewhere. The fix has the effect of limiting, under duress, the quantity that banks can source from the “market.” So if the PBOC was no longer able to supply sufficiently as pressure exceeded some grand threshold, assuming that is what kept the yuan suppressed those five months, they had only two choices at that point – let the fix drop significantly so that China’s banks could find their “dollars” at whatever price or face illiquidity to the point of default, “dollar” insolvency, and all the rest of the nastiest consequences.

And here they are a year and a half later and still fighting the same losing battle only with an increasing intensity of that fight (especially in RMB terms), including conscription of Chinese banks to source “dollars” in whatever way they might be able. Appealing to the offshore bond market rather than the offshore “dollar” market could be a slightly more effective alternative, but in the more important sense it only confirms that much more what I have been writing all this time – the “nightmare scenario.” For most people, the worst case is crash, panic, default. That may usually appear to be the case but only given a starting point of normalcy.

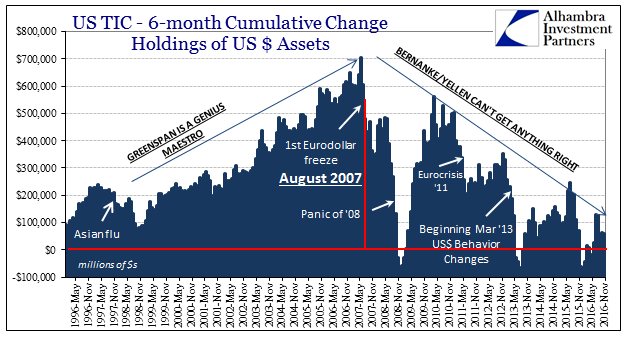

(Click on image to enlarge)

It is 2017 and the last time the word normal could be most realistically used to describe the global monetary condition was in early 2007 ten years ago, meaning that in every way crash is not the worst case. The nightmare scenario is repeating the same malfuction over and over and over without the possibility of resolution. No matter what you do, nothing will work; and by and large what you do do only makes it incrementally worse. At this point, a crash is a welcome reprieve, for it is likely the only way to recommend sufficient urgency so as to consider and allow the radical steps necessary to actually get out of the nightmare. If the nightmare problem is the “dollar short”, making yourself and your banks more “short” is beyond insanity, though regrettably understandable given the intellectual desert created by Economics.

There is no comforting of it, or treating with it. It is the eurodollar as it no longer functions. Central banks are supposed to be the absolute apex of their respective monetary systems, yet we find time and again that they are not. But because they are treated as such the public can’t even define the problem correctly. And so it goes on year after year after year. The global recovery is political, because only then will we stop listening to economists (and therefore the media) who have no idea what’s going on, let alone why. But as with China and its latest “dollar” maneuver, once you tune out Economics this really isn’t that hard to see and understand.

Disclosure:

This material has been distributed fo or informational purposes only. It is the opinion of the author and should not be considered as investment advice or a recommendation ...

more