Oh The Confusion

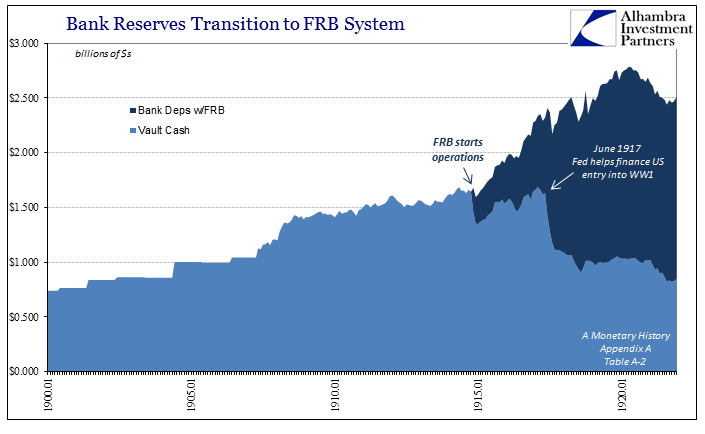

The entire idea of quantitative easing is supposed to be exceedingly simple. As I showed here, in the middle of 1917 it was. The US economy and the global monetary system moving into 2017 is nothing like that one, yet the intellectual foundations for monetary policy remain as if it was. Even in operation, QE was more PR than money; it was meant to convey specific meaning rather than specific money. It was about raising confidence at a time when there was absolutely nothing to be confident about.

That is why there had to be the “Q” to go with the “E.” This was entirely new territory but also where it was seemingly fraught with danger on every side. There was the disaster that already was, the panic and Great “Recession”, but for many that might have been simply the prelude to where the proposed solution was worse than the problem.

(Click on image to enlarge)

The policy tightrope was to do enough, but not too much; thus, the “Q.” What that one letter claimed was that monetary officials here and elsewhere knew just the “right” amount of “E” in order to gain the Goldilocks result of an economy getting back to normal (“just right”), rather than one sliding back into further “deflation” and underperformance (“too cold”), or shooting into full hyperinflationary collapse (“too hot”).

The fact that the Federal Reserve felt compelled to a second round of QE in late 2010 should have been the end of the debate; the “Q” part, at the very least, being completely disproven, a suggesting, strongly, “too cold.” Proponents can claim that subsequent events changed the calculus, that QE1 was designed for the MBS problem, not the PIIGS that arrived shortly thereafter, but in functional monetary reality, the two were inseparable. If monetary officials were so unaware of the latter as they related to the former, then there were much bigger and deeper intellectual problems beyond deciding the number for “Q.”

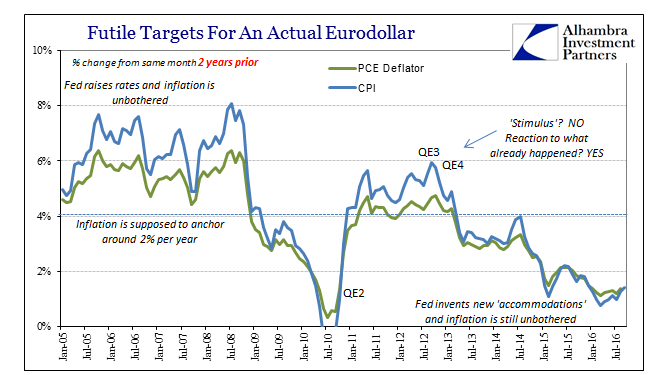

On November 4, 2010, then-Chairman of the Federal Reserve Ben Bernanke wrote for the Washington Post his infamous editorial article laying out his justifications for that second round of QE. He reiterated several reasons but they all boiled down to some form of “financial easing”, which he expected QE2 to further accomplish (hailing, as he did, the work that far done by QE1 toward that goal). It was an astounding claim as perhaps the one thing that could not describe the global monetary system, or even the US one, at that time was “easing.”

Eleven days after Bernanke’s written purpose, many prominent Fed critics signed an open letter to Bernanke urging the Fed to reconsider, to even stop the second QE just days into its start. It caused an enormous stir at the time, making some serious impression on Bernanke himself because he referred to it, non-specifically, of course, over the remaining years of his tenure. They declared:

We believe the Federal Reserve’s large-scale asset purchase plan (so-called “quantitative easing”) should be reconsidered and discontinued. We do not believe such a plan is necessary or advisable under current circumstances. The planned asset purchases risk currency debasement and inflation, and we do not think they will achieve the Fed’s objective of promoting employment.

Nearly four years after that letter was written, the mainstream especially was calling upon the signatories to admit defeat. In October 2014, Bloomberg published an article that not only called their views into question, it solicited comments from each them in order to, I believe, shame them into submission. They received the obstinate responses from nine.

Four years later, members of the group, which includes Seth Klarman of Baupost Group LLC and billionaire Paul Singer of Elliott Management Corp., are facing a different economy. U.S. companies now boast low debt, big cash piles and record profits. They’re creating jobs at the fastest average pace since 2005 and unemployment has dropped to 6.1 percent from 9.8 percent when they wrote the letter. The recovery has underpinned an almost 200 percent gain in the Standard & Poor’s 500 Index since March 9, 2009.

To say that such crowing was premature understates the problem and the issues. While it was standard stuff in late 2014, practically no one conceives of the economy that way any longer. And they should not have at that point, either, since the “dollar” was already by then “rising.” Ignorance is no defense here, just as it wasn’t in 2010 with QE1 turning into QE2; they are supposed to know what a “rising dollar” actually means. It was neither “currency debasement” as the critics charged, nor was it “recovery” as its proponents bragged.

This confusing set of circumstances was also recreated on the micro level with individual debates about certain parts of QE and monetary policy subcomponents. In March 2012, for example, St. Louis Fed economist Stephen Williamson (writing for himself rather than in any official capacity) worried about runaway inflation, too, but, unlike the Fed’s 2010 open letter critics, for the “right” reasons.

What would I be worried about, if I were Ben? After our 1970s experience, and a reading of Atkeson and Ohanian, I’m not sure why anyone thinks of inflation forecasting in terms of Phillips curves. As well, even if I were to swallow the Phillips curve – hook, line, and sinker – there are good reasons to think that there may not be any excess capacity out there. Further, in the data I’m looking at, I see plenty of reasons to think that we are in for more inflation, and one of those reasons has to do with the Fed’s wishful thinking about the power of reserve-draining tools.

In other words, he had arrived at a far different proposition to where QE worked in getting the economy going but that monetary policy tools (RRP, TDF, IOER) designed along with QE to provide a braking mechanism for when it did get things going did not. The Fed had, in his opinion, unleashed powerful stimulus that would be so powerful its practitioners were unprepared for how powerful it would be.

A year later, however, Williamson had radically changed his views. In an article in Bloomberg just a few months ago in September, Williamson was described for a debate he was having against some “doves” within and without the Fed system:

Steve Williamson of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis for the past three years or so has been trying to convince the macroeconomics world to consider a bold new theory — that central bank policy works in reverse, and that low interest rates cause low inflation.

As one of the few who are, apparently, willing to admit his mistakes, Williamson should be commended for coming to grips with reality rather than holding fast to inappropriate models. Sparring with him in that debate was former Minneapolis Fed President Narayana Kocherlakota, who answers now as one of those “doves.” On August 28, 2015, for instance, just a few days after “unexpected” global liquidations tied to Chinese currency moves that were immediately classified as Chinese “stimulus”, Kocherlakota claimed that perhaps another QE was at that time warranted:

Narayana Kocherlakota, chairman of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, said in an interview with FOX Business Network’s Liz Claman that policy makers should maintain near-zero interest rates this year and consider the possibility of additional quantitative easing.

That was also a sharp departure from his earlier positions on QE as “stimulus.” In August 2010, Kocherlakota told an audience in Marquette, Michigan that QE would lead to deflation.

To sum up, over the long run, a low fed funds rate must lead to consistent—but low—levels of deflation. The good news is that it is certainly possible to eliminate this eventuality through smart policy choices. Right now, the real safe return on short-term investments is negative because of various headwinds in the real economy. Again, using our simple arithmetic, this negative real return combined with the near-zero fed funds rate means that inflation must be positive. Eventually, the real economy will improve sufficiently that the real return to safe short-term investments will normalize at its more typical positive level. The FOMC has to be ready to increase its target rate soon thereafter.

But that QE critique, too, was right if also for the wrong reasons. He worried then that when conditions started to “normalize” inflation expectations might still be negative as a consequence of, or just in addition to, high levels of structural unemployment. In that situation, monetary policy that adheres to low-interest rates for “too long” will only “re-enforce the deflationary expectations and lead to many years of deflation.” In direct contrast to Williamson’s expectations, Kocherlakota was similarly expecting that QE would work but that in waiting too long to recognize its success monetary officials would then undermine their own achievement by being too shy about it.

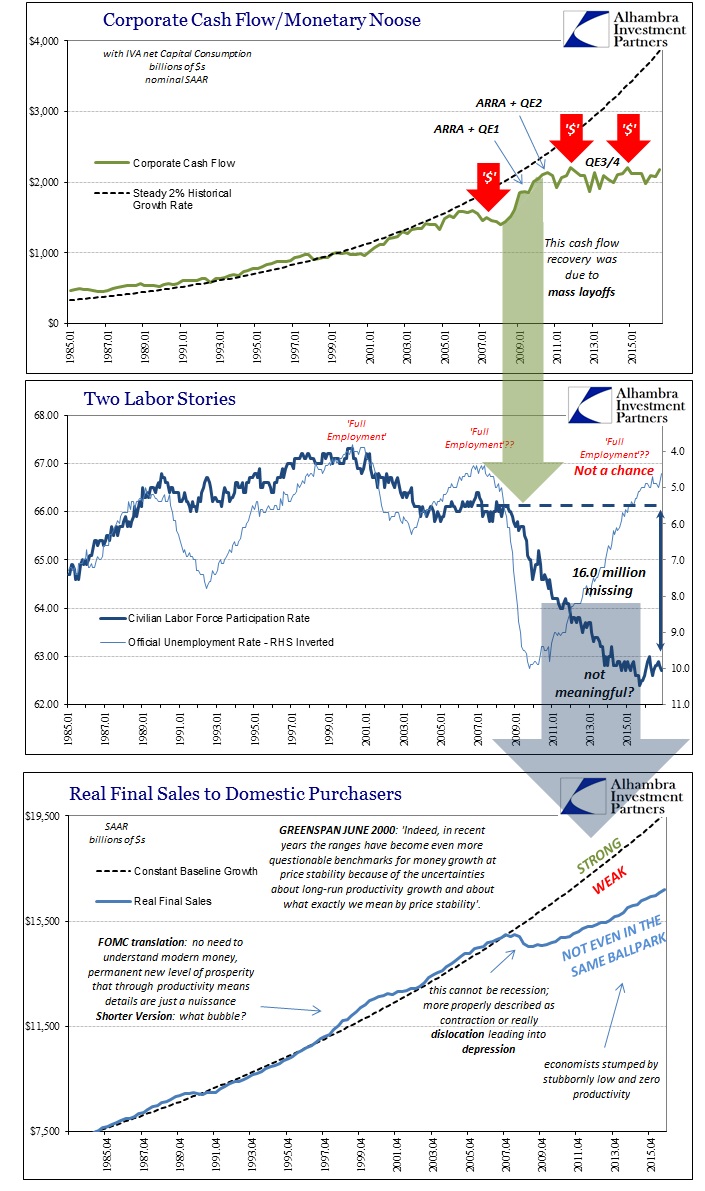

What is importantly telling about all of this back and forth is how almost all these views were altered by the events around and immediately after 2011. Because of that, what is also quite clear is that there is so much confusion in Economics right now. The state of the “discipline” has been turned inside out, upside down because practically nothing has gone the way it was supposed to. Nobody, from inside economists to outside economists to policymakers themselves, has a good handle on what just happened in all these seven years. A good part of the reason is that they feel the need to divorce the “recovery” from the contraction as if it all wasn’t one single big dislocation. To Economics, that would be impossible, so in finding the impossible Economists are all over the place trying to reconcile deeply held beliefs with their disqualification.

(Click on image to enlarge)

These are, however, still the people that will be leading the “reflation” effort as it chugs forward in at least imagination. What is especially poignant to late 2016 is that in their open letter from more than six years ago, the Fed’s critics demanded what is now the centerpiece of that “reflation” paradigm:

In this case, we think improvements in tax, spending and regulatory policies must take precedence in a national growth program, not further monetary stimulus.

In the end, they may be right (I highly doubt that will be near enough), but it should at least be cause for deep apprehension that the people who still claim to have all the economic answers were many the same who thought QE would lean way too far toward runaway inflation. Money matters and there are so few who actually know why or even what that means.

(Click on image to enlarge)

Disclosure: This material has been distributed for ...

more