Of Morality Plays And Technocratic Assessments

Breaking up the big banks might provide some visceral joy, but it’s not clear to me that solves the key problem of financial fragility in modern capitalist systems.

I recently talked on C-SPAN’s BookTV about my book, Lost Decades, coauthored in Jeffry Frieden. In it, I recounted the story of how, by hubris and ignorance of the basics of finance, we mired ourselves in the biggest financial crisis in living memory.

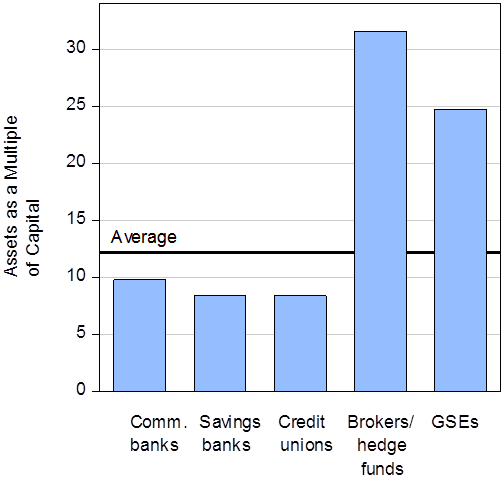

It strikes me it is useful to place assessments of the cause of the global financial crisis, over-simplistically for sure, into two categories: (1) moral hazard due to implicit government guarantees incentivizes financial entities to become overly large (aka Too Big Too Fail); or (2) government deregulation and/or financial innovation to circumvent existing government regulations such that leverage rises. While elements of both are no doubt part of the story, apportioning the relative blame is critical for determining what are the most appropriate public policies. If you believe the former, then breaking up the banks is the way to go. If you believe the latter, then measures to reduce leverage, either by implementing higher capital levies on systemically important financial institutions, and/or by making all financial institutions hold more capital against assets (and correctly risk-weighting assets) is the more efficacious route.

In Lost Decades, Jeffry Frieden and I document how hubris and ideological blinders led the G.W. Bush Administration to pursue deregulation of banking, and allowed other policymakers to ignore the hazards of high leverage (based on arguments that self-interest would induce sufficient capital holdings). The argument that it’s all “too big too fail” fails to explain why in the past massive crises of the 2008 variety did not appear (big institutions have always existed), and why the collapse of a relatively small financial institution — Lehman Brothers (not a commercial bank, by the way) — sparked such a calamity. It also fails to explain why the losses associated with many bankruptcies among many often-small savings and loan institutions necessitated such a large US government-financed bailout in the early 1990’s. So don’t focus too much on Glass-Steagall’s repeal, such as in this set of proposals. Instead, we should focus on leverage. It’s leverage that kills.

Figure 1: Leverage in 2007, measured as capital as share of assets.

Source: Greenlaw, Hatzius, Kashyap, and Shin (2008)

.In other words, the vote in favor of the Commodity Futures Modernization Act of 2000 was a bigger error (one shared by many) — I think almost all informed observers would now agree — than Glass-Steagall repeal.

Finally, it is useful to understand that higher capital charges (requiring greater holdings of capital against risk-weighted assets) (see documentation here) is already making the financial system more robust, and incentivizing downsizing of financial institutions.

Krugman discusses. Much more analysis here, and in a Hoover Institution book chapter here, as well as in Lost Decades.

Disclosure: None.