Coping With The Interest-Rate Income-Investing Crisis

In many ways, word processing is the greatest thing since sliced bread. But it has a dark side in the way text can so easily be saved and used again and again and again and long beyond the time when it has lost its relevance. A classic set of examples is the boilerplate expounding the benefits of low interest rates, and how reduction in capital costs spurs investing, and, of course, the economy.

That was all well in good for most of economic history. But it’s not relevant now. I look at countless companies all the time for my Low-Priced Stocks newsletter and other portfolios I have and frankly, cannot recall how long it’s been since I’ve seen or heard of a company scaling back investment because of high capital costs. They often scale back nowadays because prospective revenues appear inadequate, but of all the things they need to worry about, cost of capital ranks 100, on a scale of 1 to 10.

This is not 1980. The Reagan-era boilerplate, critical in its time, is nonsense today. As in 1980, we do have an interest-rate crisis. But in contrast to 1980, today’s crisis comes about because rates are too low. Interest isn’t just a cost. It’s also a source of revenue. And for many consumers it can be an important source of revenue. This is important. Consumer spending typically comprises about 68% of GDP. And as the members of the post World War II Baby Boom retire, and live longer due to improved healthcare, the portion of the vital economic sector that needs interest income is rising.

Unfortunately, the Fed’s hand is tied. It’s mandate, conceived in another era, ignores this. So until the political community (consisting of elected officials, the regulators they appoint, the civil servants they hire and the commentators who have their attention) figures out how to adapt conventional wisdom (all else being equal, lower interest rates are good) to unconventional circumstances (right now all else is NOT equal), income investors have no choice but to find ways to cope. And considering the extent to which that crowd has shown itself willing to cast aside personal agenda in favor of the greater good, don’t hold your breath waiting.

Past Performance Really Isn’t Predictive

There’s lots out there showing how well investors in general and income investors in particular can do with a portfolio that’s well balanced between equities and fixed-income securities with emphasis on the latter as one approaches and moves into retirement.

Forget it.

The lawyers are right: Past performance does not assure future outcomes. And in this case, we don’t even need the legal warnings. Elementary-school math skills (or perhaps middle-school) should suffice. Past returns benefitted, magnificently I should add, from the generational prolonged interest-rate decline launched by the Reagan-era war in interest rates and carried on by his followers. But the length of this war, while outlasting the old European 30-Years War, has no chance of coming close to the record-holding 100-Years War. Rates now are too darn close to zero. So going forward, stagnation (at a level that’s a nightmare for sellers of capital; i.e. those who depend on interest income or yield) is our “best-case” (from the vantage point of those who continue to wage the war) scenario. So the strategies that generated good returns in the past cannot and will not succeed going forward.

Coping Mechanisms For Today

Despite the inevitable disconnect between the glorious past and the much-less-glorious future, we still can’t afford to ignore the fixed-income market.

For one thing, if we were to ever have a bond-buyer’s strike (not that it could ever happen, but it can be interesting to imagine), rates would zoom up to a level where they would again become a Reagan-style crisis. So high and rising interest rates would induce boycotting bond buyers to cross the picket line and buy like crazy etc., etc., etc. and lead us right back to where we are now.

And beyond that, we do need the risk-characteristics of the fixed income market. Assuming we can manage credit risk (and given the size of the zero-credit-risk Treasury market, we absolutely positively can do that if we so choose), we can then know what we’ll get at maturity and specific interest-payment dates and limit ourselves to secondary-market risk if we can’t or choose not to hold to maturity. We can manage this through the maturity schedules into which we buy, perhaps through target-date ETFs. The returns will stink (less stinky for longer maturities featuring more secondary-market risk). But you do know what cash flows you can get and when you can get them. However stinky the returns may be, we should, by now with all the shocks and surprises we’ve experienced, know that we can never be dismissive about this sort of thing.

So how, then, can we boost our yields (recognizing, as we must, that we are going to have to take on more risk)?

Obviously, we can accept more credit risk through junk bonds (oops, I mean “high yield” bonds) or more practically for most individuals and advisors who serve them, junk-bond funds or ETFs. We also have specialized segments of the equity market that tend to be more yield oriented; Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs), Master Limited Partnerships (MLPs) and Business Development Companies (BDCs). There are various pros and cons for each and I’ll likely address them in the future, although when it comes to REITs, I’m likely to keep it brief if I cover it at all since it’s hard to top the work done in this area by Brad Thomas here in TalkMarkets and in his newsletter.

As to MLPs, if you consider them, make sure your tax accountant isn’t armed or dangerous lest he or she do nasty things to you that may or may not include the carving of “#%&@K-1s!” across your brow.

As a former (mid-1980s) junk-bond fund manager, I’ll probably get to those down the road, along with BDCs, equity-issuing companies in the business of lending to and/or investing in smaller enterprises. BDCs, like REITS, have special tax-motivated structures and have operating processes and risk-return characteristics that remind me a lot of junk bond funds.

Finally, we get to the area I want to address now on TalkMarkets; income-oriented equities (aside from the aforementioned specialty areas).

Income Stocks

This is important, especially so if we think interest rates are likely to rise. If rates do rise in the future, it won’t be because the Fed suddenly cares about savers. (And besides, given all the “damage” done by the past collapse in rates, even a well-intentioned upward adjustment would be painful since the valuation of the income-producing assets you already acquired at inflated prices would have to weaken in order to get in line with the new set of market rates.) The most likely case for rising interest rates is a stronger economy. If that happens, yield-oriented equities could prove especially worthwhile given the potential for increasing dividends (based on increasing profits) to offset, at least partially, declines in prices. It’s the flip side of the bond situation. Just as bond interest payment don’t decline (good), so, too, they don’t rise in good times (not so good).

Our goal with income stocks isn’t rocket science. We want to maximize current yield without taking undue risk (risk that the business will experience bad times and that the company will thusly reduce or eliminate the dividend payout, which they are legally allowed to do any time they wish).

When it comes to assessing such risks, Mr. Market is not at all the manic-depressive jerk he’s portrayed as being in folklore developed by Ben Graham and perpetuated by Warren Buffett and by Graham/Buffett groupies. He’s actually a pretty smart guy, a fictitious guy, but a smart one nonetheless; so much so you can confidently assume that the higher the yield (caused, obviously by skimpier marketplace demand thus leading to share prices that are lower relative to the amount of the dividend) the greater the risk of bad things. And this is not just a matter of theoretical textbook risk. These bad things happen all the time.

I’ll demonstrate with a simple model I built on Portfolio123.

I created and saved a basic “Dividend Payers” Custom Universe that eliminates zero-yield stocks as well as ADRs and specialty income stocks (such as REITs and MLPs). It has some basic liquidity constraints in that it limits consideration to Russell 3000-type companies and requires that the value of shares traded (price times volume) amount to at least $350,000 on average over the past 60 days. I also have some rules in there that attempt to detect and eliminate very recent dividend suspensions and special dividends (a harder task than you might realize given that modern financial databases were designed back in the 1990s, at a time when dividends were considered irrelevant by too many in the investment community, or at least too many of those the database developers were talking to).

I screened this universe for stocks whose yields were the best of the best; whose yields ranked in the highest percentile within this group. As of today, there are 11 passing stocks and the average of their yields is 7.6%. Nice stuff -- or not.

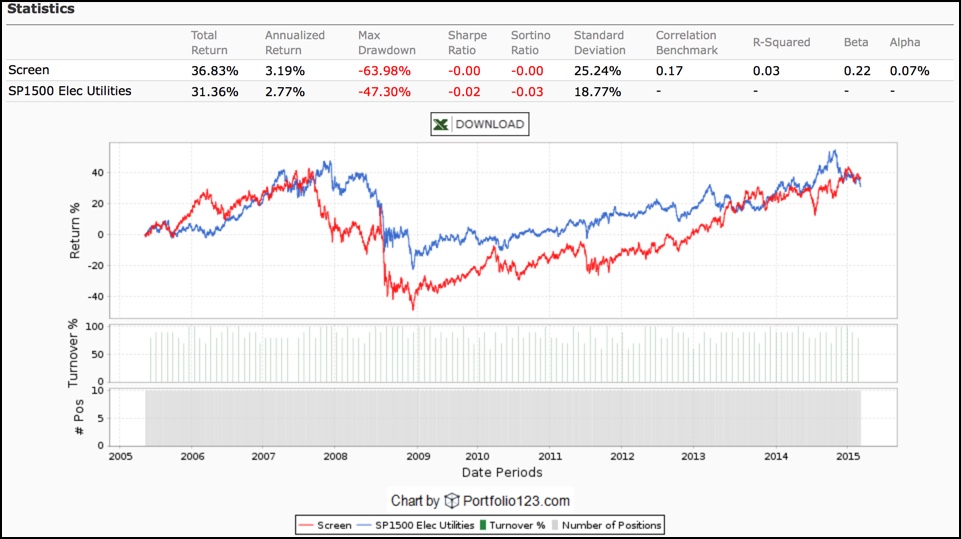

Figure 1 shows the result of a ten-year backtest of the strategy assuming 0.25% price slippage per trade and rebalancing based on a rerun of the model every three months. For a benchmark, I chose the S&P 1500 Electric Utility Index, which is probably the best choice form among those that are available to me since these issues are traditionally assumed to be the equity-market’s most fertile income-seeking hunting ground (REITs and MLPs aside).

Figure 1

Click on picture to enlarge

Ouch. That’s bad, more than enough so to make us happy to wave bye bye to that seemingly enticing 7.6% portfolio yield.

Now, let’s switch gears. Figure 2 depicts the result of a test of the same strategy except that now, I’m choosing the stocks whose yields rank in the lowest percentile. For the record, the average yield for the ten stocks that would make the cut today is 0.1%. Z-z-z-z. But check the total returns:

Figure 2

Click on picture to enlarge

Now I’ll admit the second-test may be overly contrived. No income seeker in the world is going to consider a portfolio with an average yield of 0.1%. So I ran a third test, this time focusing on ten stocks whose yields are in the middle of the best-to-worst sort. The average yield of this portfolio, as of today, would be 1.96%. The results of the backtest are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3

Click on picture to enlarge

Performance here is right smack where Mr. Market believes it should have been; in the middle.

So there we have it, the lowest yielding stocks performed best, the highest yielding stocks were worst, and the medium yielding stocks were in the middle. Risk-reward in perfect balance. Maybe when Mr. Market was young and studying for his MBA, he took good notes after all.

By the way, I haven’t lost track of the past-performance-doesn’t-assure-the-future mantra. But just as it doesn’t mean the future will resemble the past, it similarly doesn’t mean the future can’t resemble the past. Each situation must be assessed on its own.

The main difference here between past and probable future is likely to be a change in the interest-rate environment. In this, all three portfolios are likely to be similarly influenced for better or worse (more likely for worse). The differences among them relate to differences in company fundamental success, differences that are likely to persist going forward. So I think these tests are valid as expressions of the potential levels of relative returns; i.e., how the portfolios are likely to fare compared to one another.

So clearly, income-oriented equity investors cannot simply choose stocks on the basis of yield, no matter how satisfying it might feel to get an average yield of 7.6%, as opposed to 1.96% or heaven forbid, 0.1%. The capital-loss exposure may seem like something you might be willing to tolerate on day one, but as time passes and as theoretical losses become real and mount, you won’t feel so happy.

The Task Ahead of Us

Look again at Figure 3. The circa-2008 financial crisis was a disaster, but that was pretty much the case fore all strategies. Look at the other years.

Even the ten-year average that included the worst of times wasn’t a complete disaster. Recall that CDs and low (secondary-market) risk treasuries weren’t so hot. So it’s not as if we couldn’t have done worse than an average annualized return of 3.19%.

It may not be what we want. But it does suggest that by eliminating the very highest and very lowest yields, there might actually be a way to balance a desire for current income against the need to keep risk reasonable. Is there a way we can pull good things out of this broad middle ground, better things that we could get simply by focusing on the mathematical middle point?

I believe the answer is “yes.” In my next article, I’ll explain a strategy for doing do and offer some specific names.

Disclosure: No positions in stocks mentioned.