How To Analyze A Cyclical Company

“I think it’s essential to remember that just about everything is cyclical. There’s little I’m certain of, but these things are true: Cycles always prevail eventually. Nothing goes in one direction forever. Trees don’t grow to the sky. Few things go to zero. And there’s little that’s as dangerous for investor health as insistence on extrapolating today’s events into the future” - Howard Marks, The Most Important Thing

Analyzing a cyclical company presents a special set of challenges for the equity analyst. The market generally underestimates the role of the cycle, and this can result in wild swings in shares of cyclical stocks. For the smart analyst, this can create wonderful an opportunity. But to take advantage requires a robust framework to understand and value these companies. Like most things in investment, it’s difficult to get right. And like most things in investment, that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t try.

How Consensus Fails…And How to Take Advantage

As we covered in a blog post earlier this month, consensus usually gets it wrong. It gets it particularly wrong when it comes to cyclical companies. McKinsey carried out an analysis of 36 cyclical companies from 1985 to 1997, comparing consensus forecasts to actual numbers. The results showed very poor foresight on the part of analysts.

“The consensus forecasts do not predict the earnings cycle at all. In fact, except for the next year forecasts in the years following the trough, the earnings per share are forecast to follow an upward-sloping path with no future variation. You might say that the forecast does not even acknowledge the existence of a cycle” Valuation – Measuring and Managing the Value of Companies, McKinsey

Of course where consensus gets it wrong, this sets the stage for a mispricing in the market. Again from Howard Marks:

“In investing, as in life, there are very few sure things… however, there are two concepts we can hold to with confidence:

- Rule number one: most things will prove to be cyclical.

- Rule number two: some of the greatest opportunities for gain and loss come when other people forget rule one”

Of course just because consensus gets it wrong, it doesn’t necessarily mean that you can get it right. That’s why it’s important to have a robust framework for analyzing and valuing a cyclical company. This involves answering three specific questions (usually in this order):

- To what extent is the company cyclical and to what extent is it secular?

- What drives the cycle?

- Where are we in the cycle and what does a “normalized” year look like?

Cyclical Versus Secular

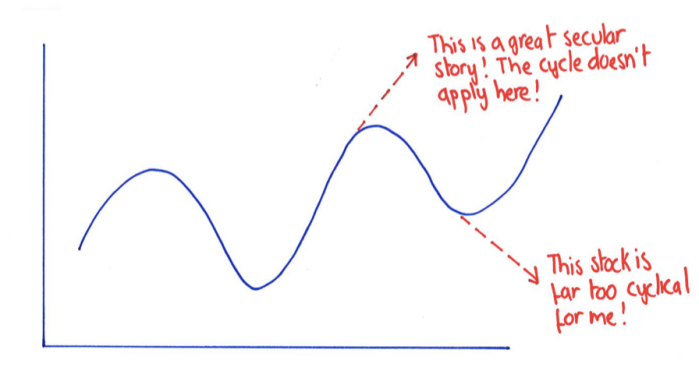

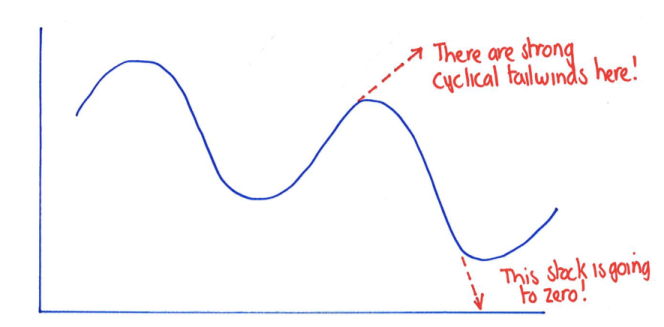

No company is purely secular or purely cyclical – usually both forces are present simultaneously. In the short term, cyclical movements can be mistaken for a secular change and vice versa – one of the reasons why analysts get it wrong. So disaggregating the two is important.

A company may operate in a cyclical industry, but over the long run there are good reasons to expect the earnings pool to rise. One example is Kone, a Finnish company that manufactures and services elevators. Over the long term there is growing demand from urbanization in emerging markets and the shift to taller structures in cities. But in the short term, earnings are strongly affected by the construction cycle. Separating out these two impacts is a key challenge for the investor. As shown in the chart below, investors can fall into two traps. They over-extrapolate on the upside, believing that the cycle no longer applies to this stock. And at the trough, investors become overly obsessed by the cycle, and forget entirely that there is a positive secular driver underlying the cycle.

Equally investors may be dealing with a company in secular decline, but that decline has been disguised by the cycle. An example might be Viacom, where over the long term their revenues are being eaten away by fragmentation. But in the short term the earnings are driven by a positive advertising cycle.

It is the unenviable job of the analyst to consider the extent to which the company is experiencing cyclical versus secular growth (or decline). Once you have determined this, the hard work really begins.

What are the Drivers of the Cycle?

Understanding where you are in the cycle is part art and part science. The first thing to make sure you understand is what drives the cycle. This could include

- Commodity prices. The revenues of a resource company will be directly linked to the price of the commodity it sells. Companies that supply into the resource sector will also be impacted (albeit indirectly) by the price of the relevant commodity.

- Economic growth. Industrial and consumer goods companies are often driven by the general economic cycle. The geographical exposure of the company will determine what economic cycle you need to track (European, Global, Asian?)

- Supply and Demand. In many cases the cycle will fluctuate with supply and demand of a particular product or service. In these cases it will be important to understand both the supply side and the demand side of the equation. For example pricing in the cruise industry is dependent on supply of cruise ships versus demand for cruises from customers. The dynamics of both sides need to be well understood.

Furthermore it is necessary to understand how these drivers impact the company. Does the company generate fixed volumes, with prices varying over the cycle? (often the case with resource companies). Or do prices remain relatively fixed with volumes changing according to demand? (as with construction companies). Finally what is the impact on the cost base – oil companies may experience a decline in revenues but cheaper oil equipment and services can mitigate the impact by providing some relief to earnings.

Where are we in the cycle?

Understanding where we are in the cycle begins with an analysis of history. Look back at least over the last 10 years to understand how the company responded to past cycles. First, do revenues vary as expected with the cycle? This will help to establish if you have correctly identified the drivers of the cycle. What is the historical range of revenues and is there an underlying secular trend? Then look at other metrics like margins, ROIC and cash flow. What is the historical range of margins and ROIC? How leveraged is the company when revenues rise or fall? A company with a high fixed cost base may experience a sharp increase in margins for a small rise in revenues. All of these questions are critical to creating a sensible forecast.

To arrive at an intrinsic value it’s important to think about what a normalized year looks like. Somewhere midpoint between the trough and the peak of the cycle is a good place to start, but you may need to adjust that based on changes in the structure of the company and/or the industry over time. Check your normalized year against the 10-year historical average and make sure you have a good explanation for any deviation. If the company is currently making peak revenues and margins, then assume a decline towards this normalized year. If the company is making trough revenues and margins then assume an increase to normal. Analysts often choose to model one cycle before returning to a “normalized” year on the basis that this offers a more “realistic” view of earnings. However, you should remember that this kind of extrapolation is really only guesswork – most of us get it wrong. In addition variations in the short term have very little impact on the intrinsic value as it’s the long-term continuing cash flows that the valuation is most sensitive to. So focus your work on getting that part right. According to whether you think the company has secular drivers, you can then apply an appropriate growth/decline rate to your normalized year.

“Continuing value must be based on a normalized level of profits, not a peak or a trough” - Valuation, McKinsey

Analyzing a cyclical company sometimes feels like an overwhelming task given all the moving parts. More than with other types of companies, it’s important not to get swallowed up by the detail. The hallmark of a great analyst is identifying what’s important and focusing on that. If you can identify the drivers of the cycle, and approximately where you are in the cycle then you’re already ahead of most sell-side analysts.

Disclosure: None.

Have something to say on a recent acquisition or merger? Let us know your views on the StockViews platform!