Interpreting Evidence On Forecasting Capabilities Of Futures Relative To Other Methods

Despite provision of numerous references, reader CoRev writes:

… it’s a big IF that soybeans futures are LONG TERM predictors at all.

I find skepticism of forecasting capabilities usually justified. However, when that skepticism is not supported by any citations, I consider such skepticism self-serving. Hence, I am going to go step-by-step for those who are not familiar with econometric methods and assessment metrics, in the hopes of educating people about the challenges of systematic prediction. Here I use as an example soybeans.

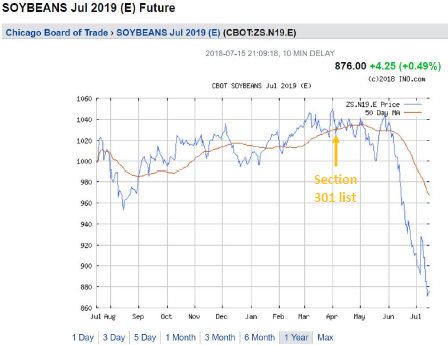

Figure 1: Soybean futures for July 2019. Source: ino.com.

Are futures unbiased predictors?

To answer this question, one can estimate the following equation, using OLS.

st+k – st = α + β(ft,k – st) + ut+k

In Table I (from Chinn and Coibion, 2014), I highlight in yellow the SOYBEAN results of this regression for soybeans, at the 3, 6 and 12 month horizons.

Table I from Chinn and Coibion, 2014.

Notice the point estimates are close to one, and statistically indistinguishable from that value, using standard errors robust to serial correlation and heteroskedasticity. Hence, the testing approach is conservative. A Wald test for the joint null α=0, β=1 is not rejected at conventional levels. That null hypothesis is consistent with the futures price being an unbiased predictor. In words, the results mean when the basis is 1%, the average change in the soybean price over the corresponding period will be…1%.

Interestingly, the R2’s are high for soybeans. In contrast, similar results are not obtained for metal commodities. In particular, the estimated β’s are often negative. Hence, we can conclude that futures are unbiased predictors of future spot soybean prices for horizons of up to a year, and have measurable predictive power.

Are futures the most precise predictors?

As is well known, mean and variance are both important. One could have an unbiased predictor, with large variance; or one with small bias, but small variance. Hence, we should look at precision.

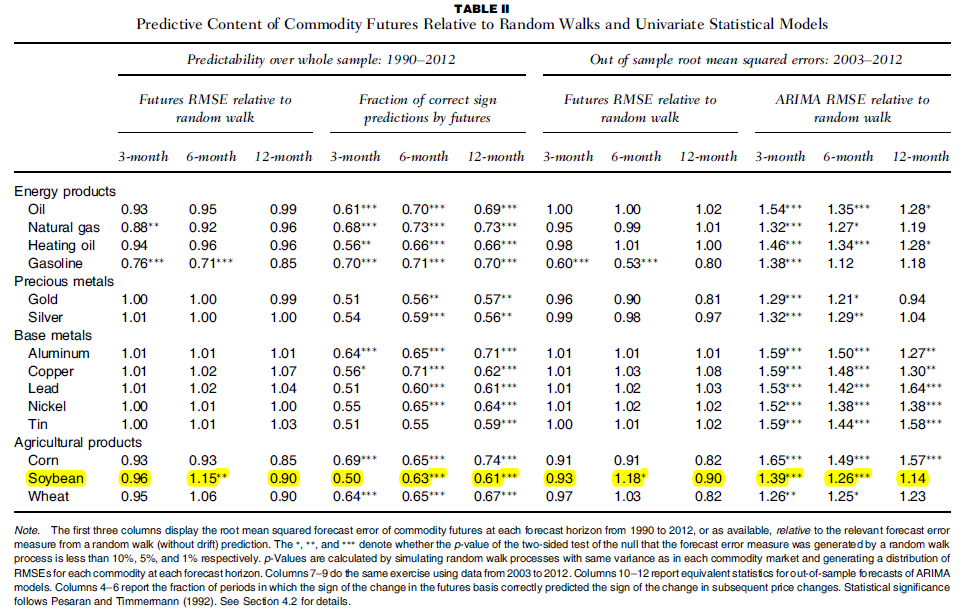

Here, one has a hard time answering the question, partly because the set of predictors is infinite. In Chinn and Coibion, we compare futures against a random walk and a ARIMA(1,1,1) model. Table II shows that at 3 and 12 month horizons, both in full sample and in a reserved out of sample (2003-12), soybean futures (highlighted yellow) had a lower root mean squared error (RMSE) than that of a random walk. At the 6 month horizon, futures are worse than a random walk, and significantly so.

Table II from Chinn and Coibion, 2014.

Even so, futures at the 6 and 12 month horizons predict correctly the sign of change in actual spot prices more than would happen by random chance (63%), and significantly so.

ARIMAs do not outperform a random walk for soybeans, and do worse by a statistically significant amount.

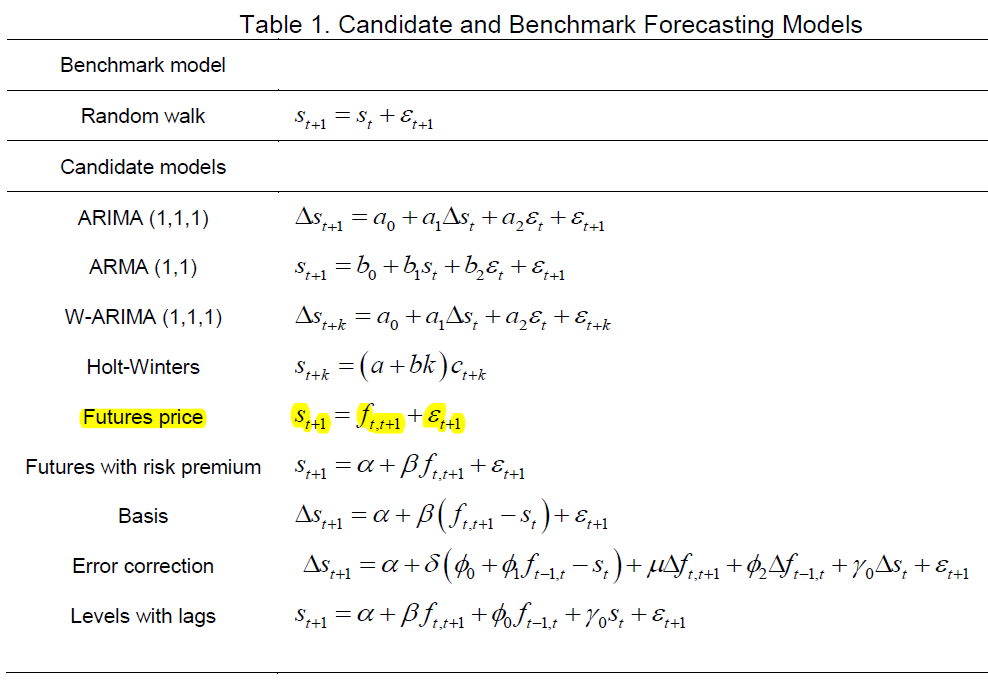

One can always argue that there’s a better model that would outperform futures. That’s hard to guard against because there are an infinite number of models to evaluate, but Reichsfeld and Roache (2011) have done a good job checking against a large set of comparators.

Table 1 from Reichsfeld and Roache, 2011.

Reichsfeld and Roache, 2011 then test to see if each predictor outperforms a random walk. If the Diebold-Mariano-West statistic is less that -1.64, then a random walk is beaten with statistical significance. As shown in the excerpt from Table 9, soybean futures do, for horizons up to a year.

Table 9 (excerpt) from Reichsfeld and Roache, 2011.

Econometric models do worse than a random walk, and statistically significantly so. Even taking into account the sampling error involved in econometric models (using the Clark-West statistic), futures continue to outperform, while econometric models only outperform a random walk model at horizons of 2 years. (Even at two years, futures outperform a random walk.)

Conclusion

Soybean futures are remarkably good predictors of future spot prices of soybeans. Hence, my best guess of soybean prices one year from today is 872.

Other futures – particularly for metals and precious metals – do not share those attributes. Nor are, as Robert Hodrick showed more than 30 years ago that for currencies, futures and forwards good or unbiased predictors of future spot rates.

Hence, one cannot make generalizations about futures, or any predictive method. Rather, one needs to do extensive, systematic and appropriate econometric work.

Disclosure: None.