You Really Have To Pick The Right Variable First

Ronald Coase was one of the few economists who was easy to admire. There are and have been a few out there, and it was Coase by and large leading the critique of the increasingly detached state of economics (really Economics). In his 1991 Nobel Prize acceptance speech, he was as usual blunt in his admonishments, saying, “I have made no innovations in high theory. My contribution to economics has been to urge the inclusion in our analysis of features of the economic system so obvious that…they have tended to be overlooked.”

In other words, long before anyone else realized it Coase had seen economics transform from a discipline centered on how an economy works to more and more abstractions defined exclusively by statistics. In the latter course, economists had become disinterested, he believed, about the basics of how the economy truly functioned on especially on an intuitive level so that they could focus on regressions of data.

That view extended, of course, into a lot of areas. In regressing variables the math can’t work unless you pare back their number. That means a lot depends upon which specific ones get included into econometric models, a cherry picking that can lead in the wrong direction. So often, the effective tax rate is treated as one of the most important in any set.

A huge subset of economists is simply obsessed with the tax rate. That has been true for a very long time, including in the Great Inflation seventies when Coase wrote:

Of course, more recently, the desire to reduce the burden of taxes has become another way of explaining why businesses adopt practices they do. In fact, the situation is such that if we ever achieved a system of limited government (and, therefore, low taxation) and the economic system were clearly seen to be competitive, we would have no explanation at all for the way in which the activities performed in the economic system are divided between firms. We would be unable to explain why General Motors was not a dominant factor in the coal industry, or why A & P did not manufacture airplanes.

For many Economists, taxes have become so important in their math that if taxation were to truly drop low enough they really wouldn’t know where or how to begin. We aren’t quite where Coase was thinking more than four decades ago, but the US tax system is nowhere near as oppressive as it was at that time. That should make a big difference, but it doesn’t seem mean to anything.

Economists persist on making so much out of taxation, and changes to it (to be clear, this is purely an economic argument about the possible effects of tax law changes, not an argument for or against them on any other grounds). In one other interesting tidbit taken from last December’s FRBNY Primary Dealer survey, 16 out of the 23 responses rated as “very important” expected changes in the outlook for US tax policy (under Trump) for setting market expectations in 10-year UST yields. By comparison, only 2 dealers thought changes in the outlook for monetary policy was likewise “very important” for the same thing.

There is a pervasive belief and not just in Economics that tax cuts are some magic economic elixir. This really isn’t surprising given that they are simply the fiscal side of something like QE. It is hard-coded, literally, into Economists and their models that “stimulus” always works.

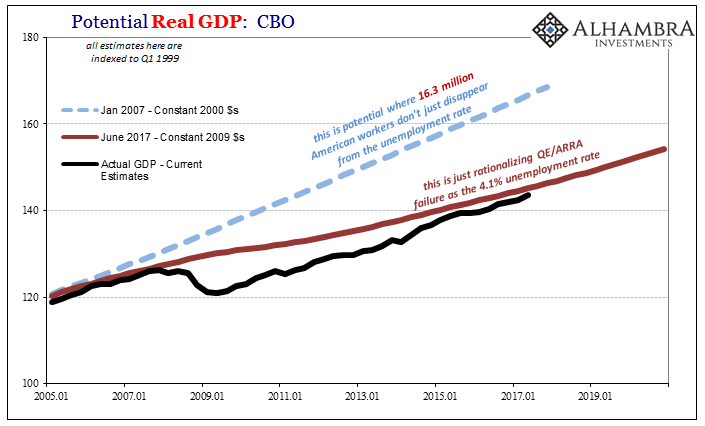

What’s different now where a tax proposal is finally on the table is that there is a clear numbers problem. What I mean by that is after ten years of monetary “stimulus” that had no effect, to reconcile that lack of recovery has meant a material write down for economic potential.

(Click on image to enlarge)

Almost all “stimulus”, it is believed, works through the demand side of the economy. Since this time none of it did, orthodox models like those employed by the Federal Reserve or Congressional Budget Office (CBO) have had to drastically lower US economic potential in order to try to account for how stimulus always works but didn’t this time. It was the supply side, you see, and therefore monetary “stimulus” didn’t fail, it never had a chance to succeed.

This is all convoluted junk science, of course, since the easy answer is monetary “stimulus” doesn’t always work, or ever work, a fact actually pretty well established right at the start by 2008.

But if you believe otherwise, because the statistical regressions are all that matter to you, then you have arrived at a bit of quandary when it comes to fiscal “stimulus.” Tax cuts can’t change the supply side by all that much, even when they might be targeted toward capex and productive investments (as empirically established by the ARRA that did nothing to boost estimates of potential, let alone real potential).

To believe that altering tax policy is going to lead to such positive demand-side effects that they would raise output way above potential for a prolonged period requires making the case for how they will really alter even more basic economic propositions – like accounting for the how it got so bad in the first place. That’s where the US Treasury is today, only without making any case for the more important second part.

In estimates put out recently, tax reform according to the Treasury Department is expected to lead to a surge in economic growth, a baseline of 2.9% over the next ten years. The CBO, which uses different models but constructed in the same way, in its latest estimates for potential sees long growth rising to at best 1.9%. That’s a full 1% increase better than potential based on tax cuts/reform alone?

Ronald Coase warned against this kind of thinking, math first. That growth rate is based on nothing more than subjective regressions rather than grounded in a solid understanding of what has actually gone on over the last decade; taking still assumptions about what “should happen” that aren’t related at all to what actually did (or didn’t) already. Democratic Senator Chuck Schumer blasted the estimates as “nothing more than one page of fake math” and I’m afraid I have to agree on that limited basis (I don’t care about the politics D vs. R).

(Click on image to enlarge)

For tax reform to have a magic bean effect it would first have to address not just the last decade but even more than that. CBO estimates for economic potential were falling long before 2008, meaning that the Great “Recession” wasn’t the real cause of the drop but instead the event that locked this disastrous condition into place. The US economy started stumbling back when QE was strictly a much derided Japanese affair.

In January 2007, for example, the models figured that long run potential output would gently decelerate to about 2.45% by now as a result of graying demographic shifts; hardly the catastrophe that Economists talk about today in attempting to pin blame of demand side failure on Baby Boomer retirements.

(Click on image to enlarge)

The much bigger issue is what happened into and after the dot-com recession in the very first years of the 21st century. It wasn’t thought to be all that much ten years ago, but right now it looks to have been the start of something big.

What happened in the middle 2000’s that could account for such a devastating weakening in economic potential ahead of the Great “Recession?” It’s almost as if at the dawn of the new millennium someone just flipped the switch to “off” (on American labor).

(Click on image to enlarge)

(Click on image to enlarge)

(Click on image to enlarge)

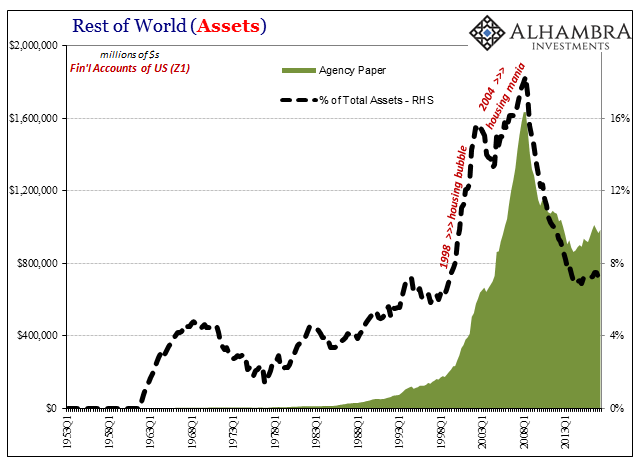

Federal Reserve monetary policy didn’t work so well that time, either. Despite a federal funds target brought down all the way to 1% (from 6.5%), what followed the very mild dot-com recession was somehow a “jobless” recovery. Many people mistakenly believe that unleashed the housing bubble to sort of rescue the US economy from that state, but the housing bubble went much further back in time than 2003.

(Click on image to enlarge)

(Click on image to enlarge)

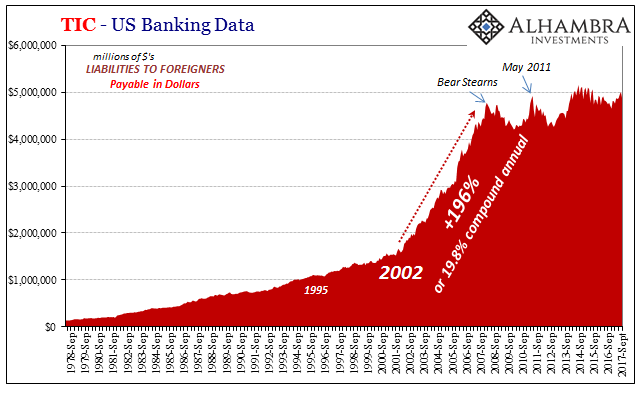

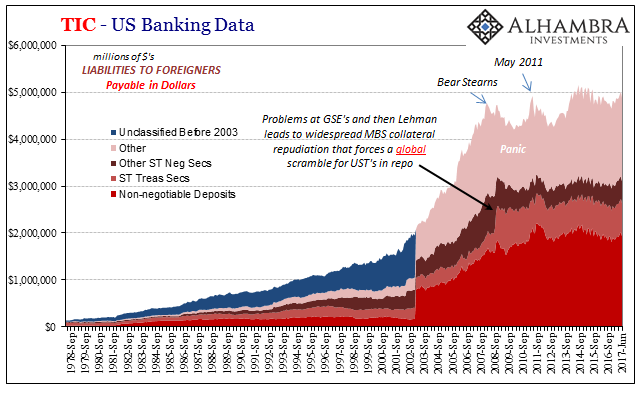

Growth in the eurodollar system, meaning a global monetary expansion of capacity, was the final part necessary to unleash Ross Perot’s “giant sucking sound.” The offshoring of manufacturing capacity (negative supply side) especially to China simply doesn’t work without “dollars” and eurodollar-based debt both to finance the transformation (which was terribly expensive) and then constantly lubricate the system thereafter.

But as the manufacturing base departed for foreign shores, the US system was kept in a low-grade capacity in the middle 2000’s by the other part of the eurodollar expansion – the debt bubble that boosted housing into a mania. It wasn’t monetary policy that brought about this brief, artificial economic reprieve it was instead especially European banks’ collective appetite for US$ securities they could easily finance via the eurodollar system’s rapid, rapacious growth (especially because in some ways, like repo, it became literally self-funding).

(Click on image to enlarge)

(Click on image to enlarge)

Not only does it account for why US growth didn’t fall off so severely until 2008, it also tells us why the Fed couldn’t seem to “stimulate” during and after the mildest recession on record and then why its “rate hikes” didn’t seem to do much, either. The central bank was a complete bystander as their R* fell down to where it now can’t possibly get up on these terms.

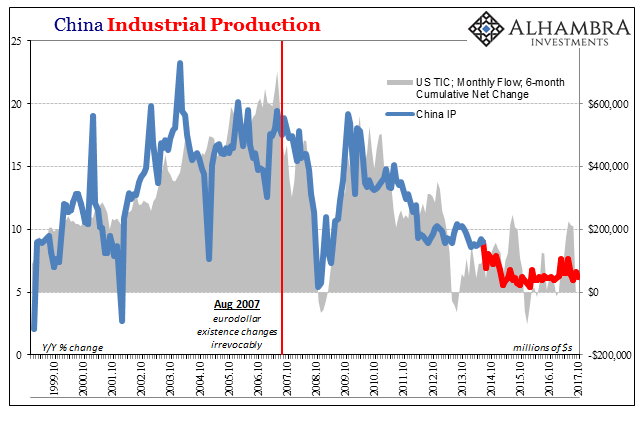

What really happened after the Great “Recession” was equally simple; without the credit expansion fueled by the eurodollar’s ascent the US economy was exposed to its hollowed out baseline. And this is true also for the other side, the EM economies that were once “miracles” of the eurodollar on the way up have turned to nightmares without its parabolic infusions of monetary energy.

(Click on image to enlarge)

(Click on image to enlarge)

It’s hard to imagine how relatively minor adjustments to the tax code, or even its massive overhaul for that matter, changes all this. The US economic problem is not some small matter to be fixed in the course of fine tuning one of the usual suspect policy variables. Coase was right, you can’t just undo all that has happened in the 21st without first addressing the complete and exhaustive economic history of the 21st century just because taxes are an easier input to statistical equations.

Economic potential, however, is still there as instead it really was the “stimulus” of monetary and fiscal policies that utterly failed because they were the wrong things for the wrong time. To achieve it, though, requires a radical, categorical change in the one thing common to all these issues. And that ain’t the tax rate.

(Click on image to enlarge)

(Click on image to enlarge)

Disclosure: None.