What Will Prevent Oil Prices From Dropping Or Increasing Forever?

The recent fall in oil prices has been the subject of a number of debates and analyses. A great deal of this discussion has focused on whether this price movement is conjectural or permanent. In a previous contribution to Seeking Alpha, I have taken a position on this issue. In my view, the phenomenon might be long-lasting due to three reasons.

First, that the current deflation in China would have contributed to the slowdown of its economy. That, together with the decision of the Chinese government to introduce electric vehicles in their fleet to alleviate their high levels of air pollution, translated into a lower demand and a lower international price for the fossil fuel.

Second, that the boom of shale gas in the U.S. has led to a drop in oil prices as a result of an increase in the production of it. That's either because an upsurge of this type of gas production is simultaneously an increase of shale oil, or because a significant portion of excess shale gas becomes diesel, reducing U.S. demand for oil and oil imports.

Third, the worsening of climate change would have prompted the switch from oil to renewable and non-renewable energy alternatives and the electrification of the automobile industry in the world. That would have started to be reflected in a decreased demand for diesel and gasoline.

A month and a half later, my contribution was complemented by a Washington Post article. To begin, there is the possible decrease in Chinese demand, evidenced by a recent fall in oil consumption in Europe and Japan was supplemented. In addition, with information from the Energy Information Administration (EIA), it was reported that at present, thanks to the oil shale revolution, the U.S. was producing two times more oil than a decade ago and that other countries (Canada, Russia and Syria) had begun to produce more oil, all of which would have influenced prices. Note in this connection that the decision in late November last year of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) not to reduce its oil production to maintain their share of the market which led to a further fall in the price of oil would have been aimed at displacing U.S. shale drillers from the oil market. Lastly, my argument about electrification of the global automotive industry was reinforced with data (also from the EIA) on use of less fuel in vehicles in the U.S. in 2014 as compared to 2008.

In this article, I intend to reconcile the notion of a permanent fall of oil prices with the contention that "oil prices won't drop forever" I endorsed in a 2009 piece published both on Industrial Minerals and EV World. And there's the fact that global warming is already forcing many countries to reduce their carbon dioxide emissions so as to avoid climate change. There's also the argument that in about a decade peak oil is likely to induce most countries to further decrease their demand for oil in response to an ever-diminishing supply, so as to circumvent a new permanent hike in oil prices, that I advanced by and large in a 2012 Seeking Alpha contribution.

Let me at the outset define a permanent fall of oil prices as a possibility for it to become "the norm of the day" for a while before oil prices stabilize at a significantly lower level. What I am therefore suggesting, in a more general way, is that to conceptualize an enduring downfall or (in fact ) a permanent upsurge of oil prices, three major elements would come into play: one, a considerable downward or upward movement of prices due to structural factors; two, a foreseeable reaction from market and other underlying forces that proves insufficient to return to the original situation; and three, a price stabilization at a significantly lower or higher level and for a reasonably long period of time.

Now take a look once again at the three structural factors I put forward to make my original case, in the context of the above mentioned assertions, with one single modification. For the purpose of consistency and clarity, the decision of the Chinese government to introduce electric vehicles in their fleet to alleviate their high levels of air pollution will be taken up as part of the third (instead of the first) fundamental element explaining the permanent fall of oil prices.

Oil Prices Won't Drop Forever

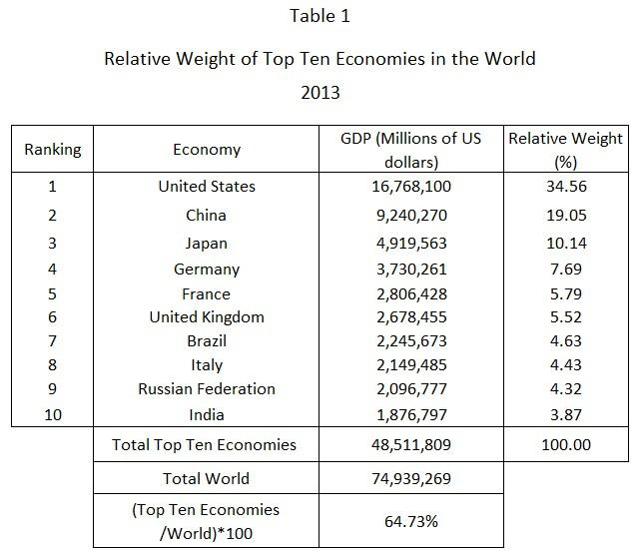

First, we need to see whether the current oil price drop could eventually stimulate demand growth for the fossil fuel bringing back "business as usual" in China, Japan and Europe. In Table 1, I present numbers on GDP in 2013 for the top ten economies of the world (including, the U.S., China, Japan and the largest European markets). This is most relevant as they constitute almost 2/3 of total world GDP and have varying degrees of participation in the global economy with the U.S. and China accounting for 54% of the top 10 economies and 35% of the world.

Source: The World Bank.

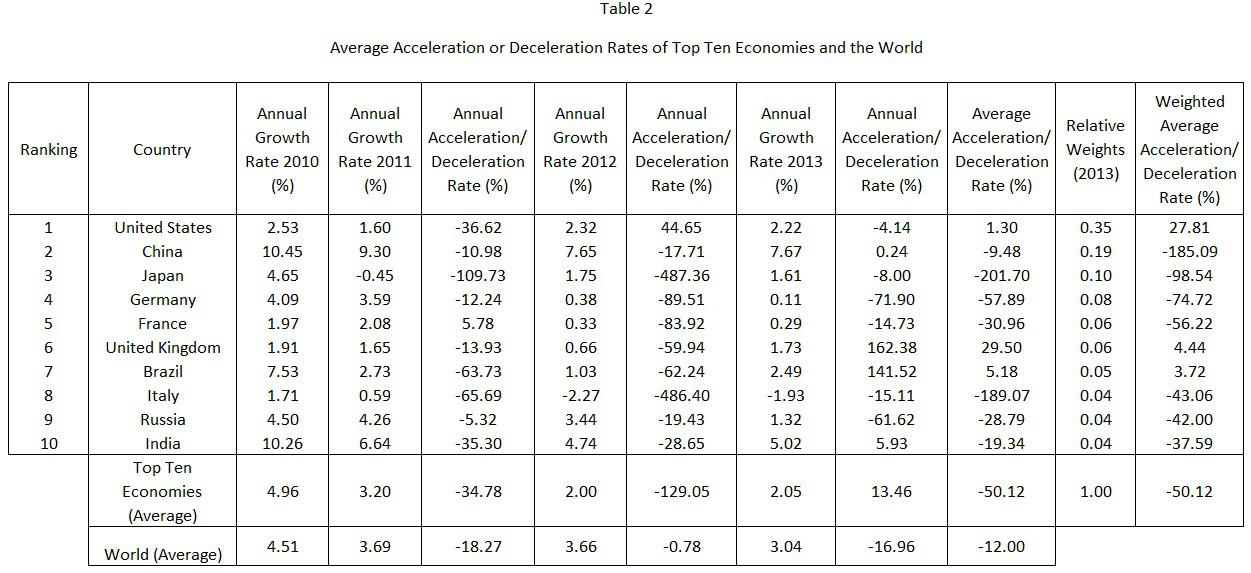

Next, in Table 2 I examine these economies' growth rates and, better still, the percent variation of those growth rates, that is their acceleration or deceleration rates over the period 2010-13. Two types of acceleration/deceleration rates were calculated; one not considering the relative weight of the different economies, and another taking those weights into account.

Click on picture to enlarge

Source: The World Bank.

Weighted acceleration and deceleration rates were obtained by separate, considering each country's relative weight in the group of the ten largest economies of the world. In this context, the average acceleration rate of the U.S. economy jumped from 1.3% to 27.81%, whereas that of China went from -9.48% down to -185.09%. By so doing, we are able to come up with a more realistic view of the state of the world economy.

Overall, the findings confirm that over the period 2010-13 both the top 10 economies and the world economy underwent (on average) a process of deceleration but also that some acceleration took place in three important countries (the United States, United Kingdom and Brazil), which (together) accounted for 45% of the top 10 economies of the world in 2013. We can't say much more at this juncture about the U.K. and Brazil.

However, based on the announcement that in the third quarter of 2014 the largest market on earth reached the highest quarterly growth rate (5%) in many years, one can imagine this trend may have intensified in the U.S. in 2014. Given the weight of the U.S. economy in the world, it can further be argued that this country's acceleration is likely to contribute to preventing oil prices from falling indefinitely. In fact, following a recent oil price article, U.S. oil demand seems to be alive and well nowadays.

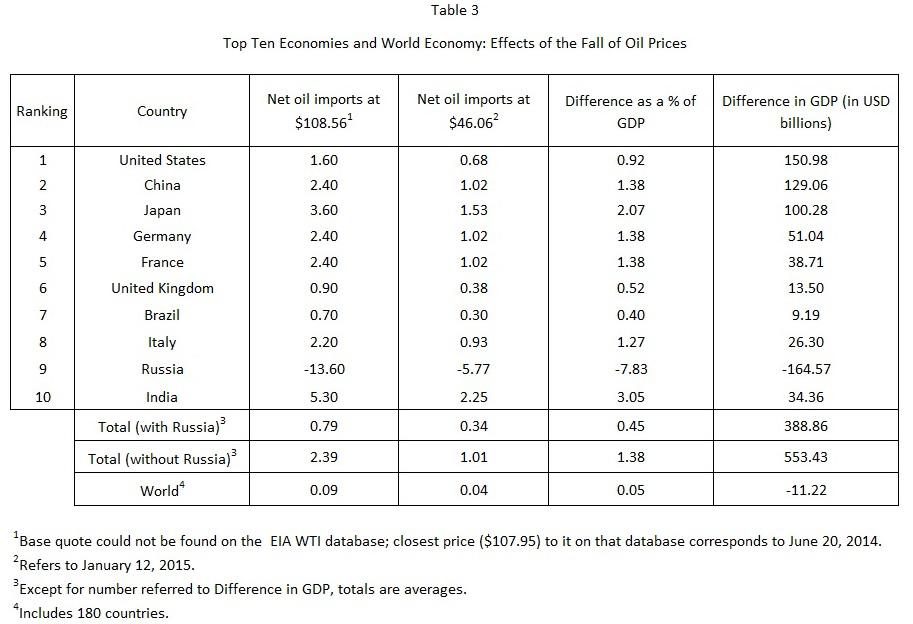

Lastly, to close this issue, we must inquire into the actual effects of the fall of oil prices on the top ten economies and the world. These were estimated by updating data from a Wall Street Journal blog on winners and losers of the recent oil price downfall. Those numbers refer to net oil imports at the price of oil on June 20, 2014, and net oil imports at the price of oil on Jan. 12, 2015, which by subtraction allow us to calculate all country effects both as a percentage of GDP and in USD billions in GDP.

In general, over that period, these effects would have translated into 0.39% of GDP for all top 10 economies (including Russia), 1.12% of GDP (not including Russia), 0.04% of world GDP; 374 USD billions for the top ten economies (with Russia), 514 USD billions (without Russia), and only 11 USD billions for the world. While based on this information it's difficult to predict how exactly all of this will influence oil prices, we can anticipate a not-too-strong impact on them. All of these outcomes further ratify my view that because oil prices are falling due to structural reasons, a positive rebound effect is not likely to bring the situation back under control from one day to another.

Click on picture to enlarge

Source: Blogs WSJ and EIA.

Second, following the decision of the OPEC not to cut oil production to preserve their market share in detriment of the U.S. shale oil producers, a considerable discussion has arisen regarding two important topics. There is the extent to which shale oil producers are prepared to resist the downfall of oil prices staying in business, and the effects of their going out of business on the U.S. economy.

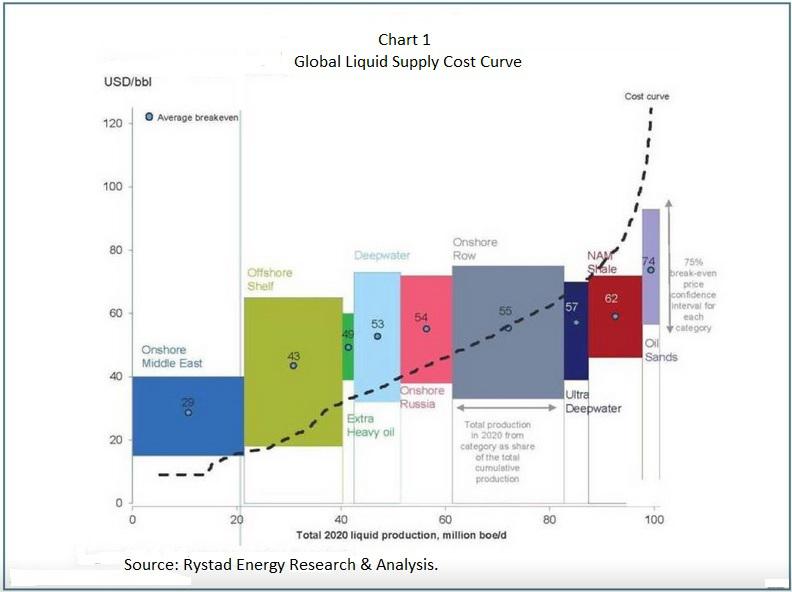

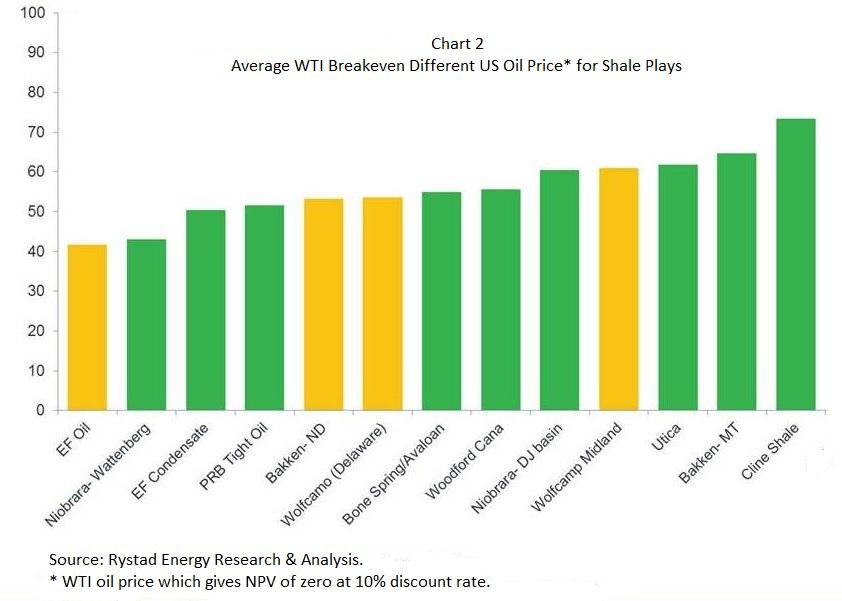

Regarding the first issue, while it's possible to foresee a considerable damage for some companies, evidence is also accumulating that "oil shales are not the highest cost sources of supply" so that other shale drillers could actually continue experiencing sustainable growth in the years to come provided the oil price is sufficiently high (see Charts 1 and 2).

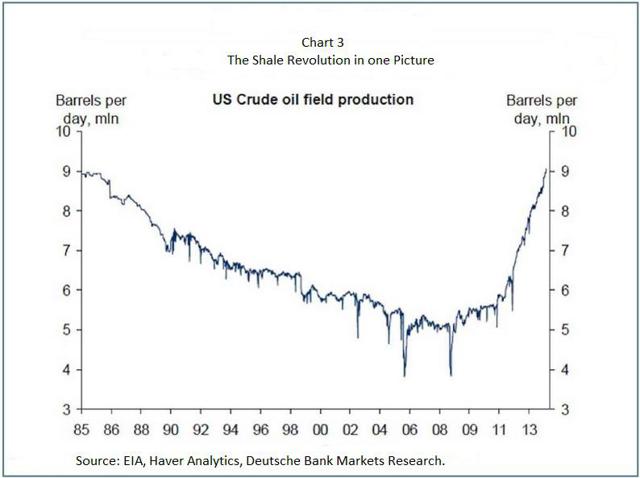

Here some words need to be said regarding the structural character of the shale oil and gas revolution in the U.S. As a recent scientific article published on both energy policy and resources for the future suggests, this new way of doing things didn't occur all of a sudden, but rather took about 40 years to develop and consolidate through two stages: an innovation stage and a scaling up stage. Furthermore, in Chart 3 it's clear that by 2009 the shale revolution was just about to start which makes us think that either other or no structural conditions were present at the time to prompt that downfall in oil prices. This explains why the 2009 oil price downfall can't be taken as permanent and was soon followed by a price rebound.

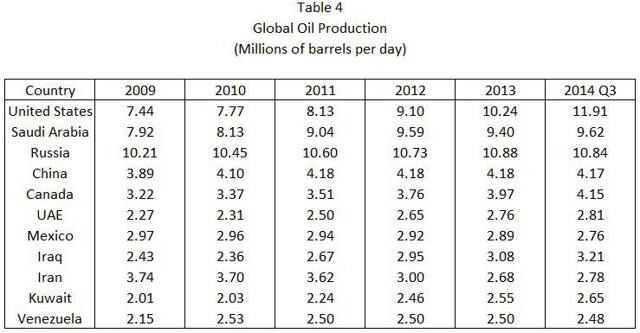

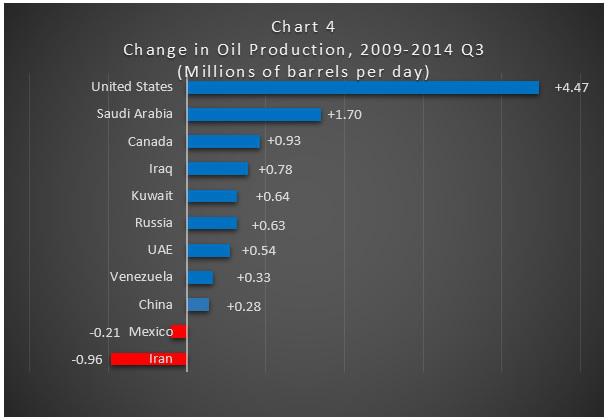

Lastly, these new structural conditions would have transformed the U.S. into the major player of the oil industry today, something no one anticipated back in 2008-09 when oil prices also collapsed (see Table 4 and Chart 4).

Source: Financial Post.

Source: Financial Post.

As for the second problem, a recent article published on oil price takes up the issue from a financial perspective arguing that if oil prices dip below $70 per barrel, some oil shale companies that offered junk bonds may have difficulties to pay back bond holders, incur losses in the coming weeks and months and, in the opinion of conspicuous writers such as Paul Krugman, eventually lead to some kind of contraction of the U.S. economy. However, as the previous oil price article suggests, junk bond debt in energy still account for a small part (16%) of the overall junk bond market in the U.S. and as long as low interest rates are sustained, demand for junk bonds could remain high so that oil companies will likely be able to restructure their liabilities and maintain access to capital. In addition, many drillers may have "hedged themselves, locking in prices for a certain amount of production" to avoid an immediate "existential" crisis.

Continue reading this article here.

Disclosure: None