Top Ten Reasons The Fed Raises Interest Rates When There Is No Inflation

Why would the Fed raise interest rates where there is little inflation? This is an important question to ask, I think, because the Fed is tightening rates while tax revenue is down and while any tightening could throw the nation into recession.

I believe there are at least ten top probable reasons why the Fed is raising rates, starting with the December, 2016 increase:

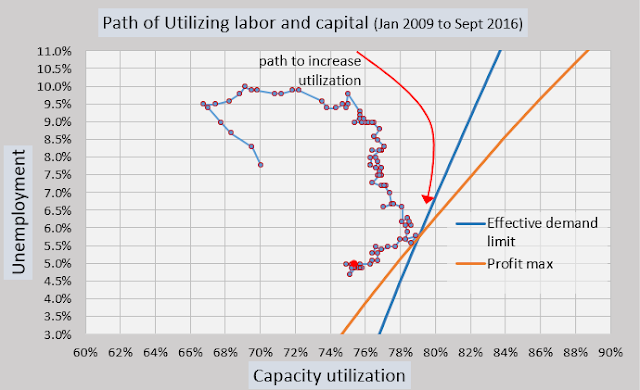

1. The Fed is misreading the effective demand limit, as assessed by Edward Lambert. Christmas shopping was below par and should sound a warning. The chart by professor Lambert explains the effective demand limit and the closing of the business cycle. Inflation is simply not a concern to Dr. Lambert:

|

| By Permission of Edward Lambert |

2. The Fed cannot raise rates significantly to stop rising inflation later on. That tool that Paul Volcker possessed, has been taken away from the Fed due to the massive demand for collateral for loans, deals, derivatives, bank capital requirements, etc. This early attempt to raise rates is, for me at least, a proof that collateral and clearing houses do matter now, in a way that was not even foreseen before asset backed collateral failed in the Great Recession. While holding bonds used as collateral to redemption insures receiving the full dollar amount you paid for the bond, the market price of bonds are marked to market by the clearing houses daily. The Fed does not have the power to tackle an inflation that existed in the 1970's where prices for goods and services changed multiple times in a week! Therefore, the Fed is paranoid about inflation prematurely due to this limitation on its powers.

3. The banks have bet on low rates and continue to bet on low rates and counterparties often take the fixed high interest side of swaps. This is not always the case, as Japanese banks have begun taking the fixed higher side of the bet. However the swap or loan is arranged, the counterparties to the lending banks put up collateral, bonds. It is necessary that the counterparties be sound and here are quotations showing why. Banks must know where their counterparties stand:

Especially in times of market stress, multiple collateral settlement fails or non-response to queries might suggest underlying problems. Even if not indicative of a failing counterparty, fails can still damage a firm’s reputation, making it hard to build relationships and win business. Replacing expected collateral in the event of a fail can be a significant funding cost, depending on liquidity levels and prevailing market conditions, with knock-on implications for other transactions. For banks, persistent unresolved fails could represent uncollateralised derivatives exposures, leading to extra capital charges under Basel III...

...In such an interconnected industry, firms are only as strong as their weakest link. To avoid both higher cost and greater regulatory sanction therefore, there is a strong case for utilising shared solutions for non-competitive functions that promote operational efficiencies, industry standardisation, and mutualisation of costs.

A tutorial for financial collateral usage is found at the Lexis Nexis blog. Here is a particularly interesting passage:

This means that assets become less good quality collateral as their credit quality declines. For instance, if a government bond falls in value, perhaps due to sovereign risk, then all those parties who have used that bond as collateral have to find extra funds to meet the resulting collateral calls. A systemic liquidity drain is possible if many bonds from the same government are widely used as collateral. (The reverse of this effect – artificially low term interest rates due to the excess demand for government bonds from collateral posters – is also potentially an issue.)

Collateral eligibility can be a problem, too. To see this, suppose that two parties have agreed that only a certain class of assets can be posted, such as bonds rated single A or better. If a given bond is downgraded, it may become ineligible as collateral. The poster then has to sell the bond and post a different eligible asset. These sales, if sufficiently widespread, can exacerbate the price falls caused by declining credit quality.

The Fed does not want this situation of massive collateral calls to occur, which is a meltdown of good quality collateral that needs to be replaced. It will risk recession over inflation to stop this. Inflation could throw us into a Great Depression.

I don't think that those in the Trump camp who want to bust through the new normal grasp how far the Fed is willing to go to protect the TBTF banks. If they do understand they must think that a credit crisis based Great Depression is no big deal. This depression-as-no-big-deal is an Austrian economic fallacy that needs to be resisted. As much as I would like bankers to pay for their past crimes in a way they have not, the banks themselves cannot be destroyed by attacking the new normal.

4. The Fed wants banks to continue to be bailed out by Interest On Reserves (IOR) and get a raise on those reserves. It is obvious that their counterparty risk is being mitigaged by a little, by continual bailouts to the still TBTF banks. This way capital requirements can be met more easily. Raising rates will likely be a very slow process because of the need to protect counterparty collateral.

5. The Fed would rather have recession than inflation, knowing the business cycle is ending. It wants to avoid stagflation. It would rather have the stagnation than the inflation. It may want to slow down a few asset bubbles, like high end housing and stock market exuberance and rental insanity creeping upward in many cities. As Goldman Sachs said, everything is overpriced. As Danielle Martino Booth says tax receipts in state government are in decline, and are an indicator of the ending of this business cycle. Unfortunately, inflation is not a real threat at this time as we look at reason 1.

6. The Fed is protecting the government's budget, which is vulnerable to higher rates. The Fed, then, must protect the New Normal. There will be a cap on yield increases, and the Fed will help maintain that. The Fed does not directly affect yields, as supply and demand for long bonds directly affects yields. But the Fed does create limits to much higher yields, by slowing the economy with higher Fed funds short rates. This gives those who use bonds as collateral confidence to continue to use them as collateral.

7. The Fed wants to give a little relief to insurance companies and pensions who have suffered from low rates on mandated bonds. The Fed is willing to let yields run a little higher in long bonds but not by much. The Greenspan conundrum is still in place, and yet the Fed wants to get ahead of even a talk up of inflation. It cannot afford a spike in yields as could happen if the Fed is not vigilant about reason 2 above.

8. The Fed wants some credibility without actually getting money into the hands of the folks on main street. The Fed wants stocks, which Goldman says are all overpriced, to decline in price. The Fed wants to establish credibility by raising rates as the business cycle slows down. Two issues are at work here and you would have to be a fly on the wall to get the real scoop:

A, it seems procyclical to take away the punch bowl as the party is winding down. It wasn't, after all, much of a party to begin with.

B, banks could lend more into the real economy if rates were a teeny bit higher, as long as you don't hurt the counterparties. This doesn't mean they would lend more into the real economy.

9. The Fed is rightly afraid of breaching the zero lower bound, but raising rates in this environment could backfire. The Fed wants ammunition in the next downturn, and Yellen is old school enough to want to avoid nominal yields going too negative. She may except a little negativity but not massive negative rates. Hence the desire to raise a little higher off of zero. Trump does not oppose this plan, but he does want rates to move higher faster and that is a recipe for disaster.

10. The Fed does not believe in Milton Friedman after all. The Fed believes it is out of ammunition and it is time to retrench. That happened in 1937 and led to a continuance of the Great Depression and war. The Fed has, as Zero Hedge has said, a balance sheet of 25 percent of GDP, same as when it raised rates in '37, Some people just never learn. The Fed is believing superficial analysis about helicopter money. The Fed needs to believe in Milton Friedman. He was smarter and braver than they are. Choosing between war and helicopter money may be the only choice left, thanks to a Fed that appears paralyzed by fear.

For further reading:

What Happens If a Party Fails to Deliver Collateral in a Repo?

Disclosure: I am not an investment counselor nor am I an attorney so my views are not to be considered investment advice.