Simple Janet - The Monetary Android With A Broken Flash Drive

This is getting just plain nuts. Here is what Janet Yellen said today about the possibility of negative interest rates:

In light of the experience of European countries and others that have gone to negative rates, we’re taking a look at them again because we would want to be prepared in the event that we needed to add accommodation.“

The operative words here are “European countries” and “add accommodation”. Yet even a brief reflection on those items demonstrates that Janet is a delusional Simpleton. To adopt Jim Kunstler’s felicitous phrase about Senator Rubio’s 4-Peat incantation during the last GOP debate, our financial system is being led by a monetary android with a broken flash drive.

She says the same damn stupid thing over and over, endlessly.

Someone should tell Janet and her posse of Keynesian money printers that there is no such economic ether as “accommodation”. That’s Fed groupspeak for their utterly erroneous conceit that the US economy is everywhere and always sinking towards collapse unless it is countermanded, stimulated, supported and propped up by central bank policy intervention.

No it isn’t. Janet may prefer a dutch boy hair cut, but she’s not got her finger in the dike, nor is she warding off any other catastrophe. The deluge that is coming is actually the handiwork of the Fed and its bubble ridden Wall Street casino, not the capitalist hinterlands of main street.

There are only two tangible transmission channels through which the Fed can impact our $18 trillion main street economy, as opposed to merely subsidizing Wall Street speculators to artificially bid up the price of existing financial assets.

It can inject central bank credit conjured from thin air into the bond market in order to raise prices and lower yields. And it can falsify money market interest rates and the yield curve. Both of these effects are aimed at inducing businesses and households to borrow more than they would otherwise, and to then spend more than they produce.

That’s the old Keynesian parlor trick and, yes, it worked 50 years ago when Janet’s Keynesian professors first had their way with America’s virgin balance sheets. But now those household and business balance sheets are all used up because we are at Peak Debt, along with most of the rest of the world.

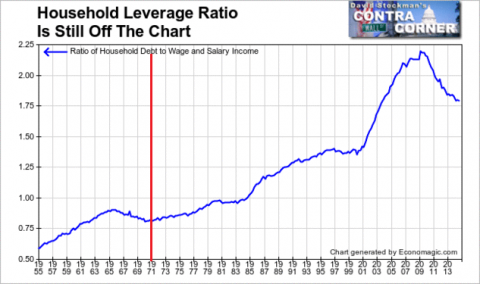

Indeed, in the case of the US household sector the massive leveraging up of wage and salary income betweenthe late 1960s and 2008 has now begun to slowly reverse.The credit string that the Fed is pushing on is evident in the chart below. But apparently Janet is still in a time warp obeying the injunctions of James Tobin’s ghost wafting up from the earlier side of the red horizontal.

Accordingly, the stimulative effect of low and ultra-low interest rates never really leaves the canyons of Wall Street. And when it does, it trickles its way into credit extensions to the weakest borrowers left in the land. That is, students and subprime auto borrowers.

Outside of those dubious precincts - where the next wave of defaults or government bailouts will surely occur - there has actually been negative growth in household debt since the financial crisis.Notwithstanding 86 months of ZIRP and its current equivalent, total household debt is still $400 billion below it pre-crisis peak, and mortgage and credit card debt are down by more than $1 trillion.

Likewise, the $2 trillion rise in total business debt outstanding has not gone into productive assets such as tangible plant, equipment and technology. It has been short-circuited into financial engineering by the false financial bubble fostered by Fed policies. That is, massive stock buybacks and M&A deal volumes have simply used the agency of the stock options obsessed C-suite to recycle newly issued business debt right back into the canyons of Wall Street.

So if 86 months of ZIRP has already proved that the old Keynesian parlor trick—–which is the say, the household and business credit channel of monetary policy transmission—-is a dead letter, why in the world would Janet think that a few more basis points through the negative side of 0.0% would make any difference?

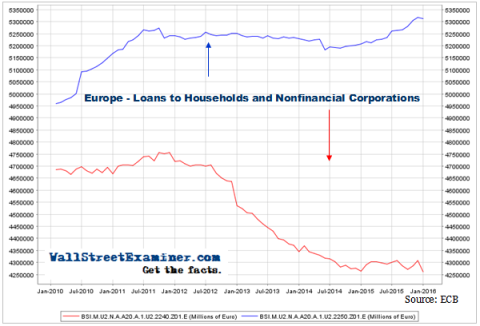

And especially after the ECB has tried it, and to no avail!As is evident from the bank loan data for the Eurozone, credit extensions to private business have been sinking since 2012 when Draghi issued his “anything” it takes ukase. The ECB’s move to negative deposit rates last year has not changed that trend in the slightest.

Likewise, household debt in Europe soared during the decade through 2010, but has been oscillating on the flat-line ever since. And the reason is beyond the power of the ECB or any central bank to remedy. Namely, European households are also at Peak Debt, meaning that central bank fiddling with negative deposit rates is pointless and irrational.

At the end of the day, don’t take my word for it. Here is Simple Janet’s written testimony. It was indeed generated by a monetary android with a broken flash drive.

Since my appearance before this Committee last July, the economy has made further progress toward the Federal Reserve’s objective of maximum employment. And while inflation is expected to remain low in the near term, in part because of the further declines in energy prices, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) expects that inflation will rise to its 2 percent objective over the medium term.

In the labor market, the number of nonfarm payroll jobs rose 2.7 million in 2015, and posted a further gain of 150,000 in January of this year. The cumulative increase in employment since its trough in early 2010, is now more than 13 million jobs. Meanwhile, the unemployment rate fell to 4.9 percent in January, 0.8 percentage point below its level a year ago and in line with the median of FOMC participants’ most recent estimates of its longer-run normal level. Other measures of labor market conditions have also shown solid improvement, with noticeable declines over the past year in the number of individuals who want and are available to work but have not actively searched recently, and in the number of people who are working part time but would rather work full time. However, these measures remain above the levels seen prior to the recession, suggesting that some slack in labor markets remains. Thus, while labor market conditions have improved substantially, there is still room for further sustainable improvement.

The strong gains in the job market last year were accompanied by a continued moderate expansion in economic activity. U.S. real gross domestic product is estimated to have increased about 1-3/4 percent in 2015. Over the course of the year, subdued foreign growth and the appreciation of the dollar restrained net exports. In the fourth quarter of last year, growth in the gross domestic product is reported to have slowed more sharply, to an annual rate of just 3/4 percent; again, growth was held back by weak net exports as well as by a negative contribution from inventory investment. Although private domestic final demand appears to have slowed somewhat in the fourth quarter, it has continued to advance. Household spending has been supported by steady job gains and solid growth in real disposable income–aided in part by the declines in oil prices. One area of particular strength has been purchases of cars and light trucks; sales of these vehicles in 2015, reached their highest level ever. In the drilling and mining sector, lower oil prices have caused companies to slash jobs and sharply cut capital outlays, but in most other sectors, business investment rose over the second half of last year. And homebuilding activity has continued to move up, on balance, although the level of new construction remains well below the longer-run levels implied by demographic trends.

Financial conditions in the United States have recently become less supportive of growth, with declines in broad measures of equity prices, higher borrowing rates for riskier borrowers, and a further appreciation of the dollar. These developments, if they prove persistent, could weigh on the outlook for economic activity and the labor market, although declines in longer-term interest rates and oil prices provide some offset. Still, ongoing employment gains and faster wage growth should support the growth of real incomes and therefore consumer spending, and global economic growth should pick up over time, supported by highly accommodative monetary policies abroad. Against this backdrop, the Committee expects that with gradual adjustments in the stance of monetary policy, economic activity will expand at a moderate pace in coming years and that labor market indicators will continue to strengthen.

As is always the case, the economic outlook is uncertain. Foreign economic developments, in particular, pose risks to U.S. economic growth. Most notably, although recent economic indicators do not suggest a sharp slowdown in Chinese growth, declines in the foreign exchange value of the renminbi have intensified uncertainty about China’s exchange rate policy and the prospects for its economy. This uncertainty led to increased volatility in global financial markets and, against the background of persistent weakness abroad, exacerbated concerns about the outlook for global growth. These growth concerns, along with strong supply conditions and high inventories, contributed to the recent fall in the prices of oil and other commodities. In turn, low commodity prices could trigger financial stresses in commodity-exporting economies, particularly in vulnerable emerging market economies, and for commodity-producing firms in many countries. Should any of these downside risks materialize, foreign activity and demand for U.S. exports could weaken and financial market conditions could tighten further.

Of course, economic growth could also exceed our projections for a number of reasons, including the possibility that low oil prices will boost U.S. economic growth more than we expect. At present, the Committee is closely monitoring global economic and financial developments, as well as assessing their implications for the labor market and inflation and the balance of risks to the outlook.

As I noted earlier, inflation continues to run below the Committee’s 2 percent objective. Overall consumer prices, as measured by the price index for personal consumption expenditures, increased just 1/2 percent over the 12 months of 2015. To a large extent, the low average pace of inflation last year can be traced to the earlier steep declines in oil prices and in the prices of other imported goods. And, given the recent further declines in the prices of oil and other commodities, as well as the further appreciation of the dollar, the Committee expects inflation to remain low in the near term.However, once oil and import prices stop falling, the downward pressure on domestic inflation from those sources should wane, and as the labor market strengthens further, inflation is expected to rise gradually to 2 percent over the medium term. In light of the current shortfall of inflation from 2 percent, the Committee is carefully monitoring actual and expected progress toward its inflation goal.

Of course, inflation expectations play an important role in the inflation process, and the Committee’s confidence in the inflation outlook depends importantly on the degree to which longer-run inflation expectations remain well anchored. It is worth noting, in this regard, that market-based measures of inflation compensation have moved down to historically low levels; our analysis suggests that changes in risk and liquidity premiums over the past year and a half contributed significantly to these declines. Some survey measures of longer-run inflation expectations are also at the low end of their recent ranges; overall, however, they have been reasonably stable.

Monetary Policy

Turning to monetary policy, the FOMC conducts policy to promote maximum employment and price stability, as required by our statutory mandate from the Congress. Last March, the Committee stated that it would be appropriate to raise the target range for the federal funds rate when it had seen further improvement in the labor market and was reasonably confident that inflation would move back to its 2 percent objective over the medium term. In December, the Committee judged that these two criteria had been satisfied and decided to raise the target range for the federal funds rate 1/4 percentage point, to between 1/4 and 1/2 percent. This increase marked the end of a seven-year period during which the federal funds rate was held near zero. The Committee did not adjust the target range in January.

The decision in December to raise the federal funds rate reflected the Committee’s assessment that, even after a modest reduction in policy accommodation, economic activity would continue to expand at a moderate pace and labor market indicators would continue to strengthen. Although inflation was running below the Committee’s longer-run objective, the FOMC judged that much of the softness in inflation was attributable totransitory factors that are likely to abate over time, and that diminishing slack in labor and product markets would help move inflation toward 2 percent. In addition, the Committee recognized that it takes time for monetary policy actions to affect economic conditions. If the FOMC delayed the start of policy normalization for too long, it might have to tighten policy relatively abruptly in the future to keep the economy from overheating and inflation from significantly overshooting its objective. Such an abrupt tightening could increase the risk of pushing the economy into recession.

It is important to note that even after this increase, the stance of monetary policy remains accommodative. The FOMC anticipates that economic conditions will evolve in a manner that will warrant only gradual increases in the federal funds rate. In addition, the Committee expects that the federal funds rate is likely to remain, for some time, below the levels that are expected to prevail in the longer run. This expectation is consistent with the view that the neutral nominal federal funds rate–defined as the value of the federal funds rate that would be neither expansionary nor contractionary if the economy was operating near potential–is currently low by historical standards and is likely to rise only gradually over time. The low level of the neutral federal funds rate may be partially attributable to a range of persistent economic headwinds–such as limited access to credit for some borrowers, weak growth abroad, and a significant appreciation of the dollar–that have weighed on aggregate demand.

Of course, monetary policy is by no means on a preset course. The actual path of the federal funds rate will depend on what incoming data tell us about the economic outlook, and we will regularly reassess what level of the federal funds rate is consistent with achieving and maintaining maximum employment and 2 percent inflation. In doing so, we will take into account a wide range of information, including measures of labor market conditions, indicators of inflation pressures and inflation expectations, and readings on financial and international developments. In particular, stronger growth or a more rapid increase in inflation than the Committee currently anticipates would suggest that the neutral federal funds rate was rising more quickly than expected, making it appropriate to raise the federal funds rate more quickly as well. Conversely, if the economy were to disappoint, a lower path of the federal funds rate would be appropriate. We are committed to our dual objectives, and we will adjust policy as appropriate to foster financial conditions consistent with the attainment of our objectives over time.

Consistent with its previous communications, the Federal Reserve used interest on excess reserves (IOER) and overnight reverse repurchase (RRP) operations to move the federal funds rate into the new target range. The adjustment to the IOER rate has been particularly important in raising the federal funds rate and short-term interest rates more generally in an environment of abundant bank reserves. Meanwhile, overnight RRP operations complement the IOER rate by establishing a soft floor on money market interest rates. The IOER rate and the overnight RRP operations allowed the FOMC to control the federal funds rate effectively without having to first shrink its balance sheet by selling a large part of its holdings of longer-term securities. The Committee judged that removing monetary policy accommodation by the traditional approach of raising short-term interest rates is preferable to selling longer-term assets because such sales could be difficult to calibrate and could generate unexpected financial market reactions.

The Committee is continuing its policy of reinvesting proceeds from maturing Treasury securities and principal payments from agency debt and mortgage-backed securities. As highlighted in the December statement, the FOMC anticipates continuing this policy “until normalization of the level of the federal funds rate is well under way.” Maintaining our sizable holdings of longer-term securities should help maintain accommodative financial conditions and reduce the risk that we might need to return the federal funds rate target to the effective lower bound in response to future adverse shocks.

Disclosure: None.