Pompeii On SF Bay?

Will a minimum wage increase induce an apocalyptic conflagration of small businesses and low wage employment? Here’s one prediction:

This is not the time to force businesses to raise prices by laying-off employees in order to stay in business.

What good is raising the minimum wage if prices go up? What good is raising the minimum wage if there are no jobs available?

Businesses will be forced to raise prices in order to absorb a 26% pay increase. Restaurants will be especially hard hit.

That is not a quote addressing the impending increase in the SF minimum wage. Rather, it’s the statement by the SF Restaurant Association regarding San Francisco’s Proposition L, in 2003 (ballot instructions here). For a current incarnation of this apocalyptic vision, one has to go no further than Michael Saltsman, in the oped pages of the Wall Street Journal:

Last fall, voters in the Bay Area cities of San Francisco and Oakland followed Seattle’s lead and approved costly new minimum-wage mandates ($15 an hour and $12.25 an hour, respectively) for most businesses in the city boundaries. Now the bills have begun arriving, and some businesses can’t pay them.

Then, as befits the research director of an organization the sometimes publishes irreproducible results (at least I can’t reproduce ‘em – maybe a more imaginative researcher could), Mr. Saltsman conducts a proof by anecdote.

In Oakland, local restaurants are raising prices by as much as 20%, with the San Francisco Chronicle reporting that “some of the city’s top restaurateurs fear they will lose customers to higher prices.” Thanks to a quirk in California law that prohibits full-service restaurants from counting tips as income, other operators—who were forced to give their best-paid employees a raise—are rethinking their business model by eliminating tips as they raise prices.

Though higher prices are a risk that some businesses were able to take, others haven’t had the option. The San Francisco retailer Borderlands Books made national news in February when the owner announced that the city’s $15 minimum wage would put him out of business, in part because the prices of his products were already printed on the covers. (A unique customer fundraiser gave Borderlands a stay of execution until at least March of 2016.)

One block away from Borderlands, a fine-dining establishment called The Abbot’s Cellar—twice selected as one of the city’s top-100 restaurants—wasn’t so lucky. The forthcoming $15 minimum wage, combined with a series of factors like the city’s soaring rents, put the business over the edge and compelled its owners to close. One of the partners told me the restaurant had no ability to absorb the added cost, and neither a miraculous increase in sales volume nor higher prices were viable options.

These aren’t isolated anecdotes. In the city’s popular SoMa neighborhood, a vegetarian diner called The Source closed in January, again citing the higher minimum wage as a factor.

I found the oped particularly resonant because just hours before reading this “piece”, I had been cautioning my students in the econometrics course I teach not to argue by anecdote, and in fact to be particularly wary of those who did. My example of the hazards of relying on anecdotes was drawn from the Card and Krueger’s 1994 American Economic Review paper on the minimum wage. Scrolling through the data set, I highlighted the fact that one particular fast food restaurant reduced employment in after the imposition of a minimum wage in NJ. Of course, those familiar with the Card-Krueger results, which rely upon a differences-in-differences approach, know that overall, average store employment increased in NJ, post-minimum wage imposition, relative to the change in PA average store employment. That is, there was a statistically significant and economically significant increase in employment, even though there were individual cases of employment falling in NJ.

Now, in the context of the impending increase in the minimum wage from $10.25 to $15, what’s going to happen? Well, first thing to mention (omitted from Mr. Saltsman’s piece) is that the minimum wage increase is phased in, so that the $15 level is achieved in 2018. Second, it’s useful to observe what has happened since the 2004 increase in the minimum wage. From L. Thompson/Seattle Times:

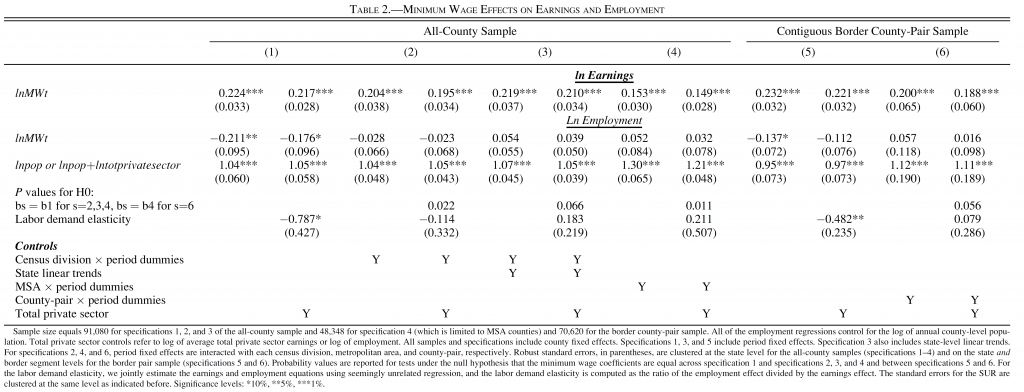

So, one can properly take into account the facts, then observe what has happened in the past, and then finally, one can appeal to statistical analyses. Dube, Lester and Reich (2010 Review of Economics and Statistics) report their estimates of the impact of minimum wage changes on income and employment.

Figure 2 from Dube et al. (2010).

In general, the results suggest that earnings rise and employment is either unaffected, or declines slightly.

Obviously, there are many different estimates, and this is but one set. And I would never rule out the possibility of significant employment effects (never say never is the lesson delivered by Don Luskin’s example). However, as previously discussed, the bulk of the evidence suggests small negative impacts on employment, if any (see e.g., [1]).

Disclosure: None.