‘Outflows’

In September 2013, the BIS took a closer look at offshore corporate issuance of EM obligors. The timing could not have been more relevant, which was very likely their point in undertaking the difficult exercise. The “taper tantrum” that summer had roiled domestic bond markets in the US, but was really focused in the offshore sections of the “dollar” system. As such, there were vulnerabilities that had developed largely ignored or misunderstood even during the months where EM’s took center stage for all the wrong reasons.

Worse, however, was what followed the events of 2013. To most, it was a one-off due to too much central bank success; from QE3 in the US, LTRO’s being paid back in Europe, and then QQE in Japan. The EM issue, many believed, would be easily handled in the context of the full global recovery that was then sure to follow. Understanding instead what the BIS was trying to relate in September 2013, by contrast, would have led to a far different range of expectations, including what would break out as the “rising dollar” just several months later.

The key sections of the report were focused on EM corporate bonds, but in that case the data is a rough proxy for more than securities, as those were only what was taking place on the surface. As the BIS detailed, EM’s, meaning mostly China and Brazil corporates, were going bananas for dollars:

The surge in OFC issuance by EME corporations is primarily due to borrowers headquartered in just two countries, China and Brazil. Chinese firms’ borrowing in OFCs shot up from less than $1 billion per annum in 2001 and 2002 to $51 billion in the 12 months up to mid-2013 (Graph C, left-hand panel). This amounts to approximately 70% of all international debt securities issued by Chinese financial and non-financial corporations.

The term “corporates” is often misleading, as it conjures primarily images of productive firms undertaking financial activities in order to complete productive uses. While that is true in a very broad sense, in reality “corporates” also encompasses financial corporations of various legal frameworks, including banks and more. The BIS at that time figured around a third of all dollar financing in this sense was due to “Chinese financial institutions that fund dollar lending in China.” It was, in short (pardon the pun), an explosion in the global “dollar” short for China and Brazil.

The “dollar” conditions for that to have happened were seemingly just that favorable. The DM world was stuck in a “new normal” where growth was at best stunted, but also far from assured (risk) even at that slow pace given the continuing almost regular financial crises that followed the Great “Recession.” EM’s were thought ready and capable especially in those early years of the “recovery” to lead the global growth paradigm, or at least to be a much better alternative to DM avenues.

Underpinning the financial considerations of “dollar” flows in that direction was as a consequence of misconstruing the global financial system even after the eurodollar panic in 2007-09 should have corrected the wrong ideas about these currencies. The “weak” dollar of the middle 2000’s seemed poised to prevail all over again in expectations, especially as it related to CNY that was by then steadily appreciating against the dollar. Therefore those prospects dominated the “dollar” explosion – at least up until the middle of 2013 when those assumptions were taken out on a stretcher.

For some reason, however, the “weak” dollar thesis prevailed right on into 2014. As the BIS also noted just months before CNY would turn “unexpectedly” lower:

As a consequence, a significant share of Chinese corporate debt securities issued in OFCs [offshore financial centers], 16%, is denominated in renminbi. That said, the US dollar remains by far the most important currency of issuance for Chinese firms, accounting for 77% of corporate issuance in OFCs. Again, this could reflect differences in the cost of funding. Dollar-denominated rates are below comparable renminbi rates and many players expect an appreciation of the Chinese currency. [emphasis added]

Lenders of “dollars” were prepared for that currency regime, and thus were hedged and priced their “lending” activities (taking many different forms, including the more exotic FX like swaps and swaptions) in that direction. From the perspective of Chinese or Brazilian “borrowers” of “dollars”, it was cheaper in terms of both interest rate as well as the expected currency direction (appreciation of the local currency).

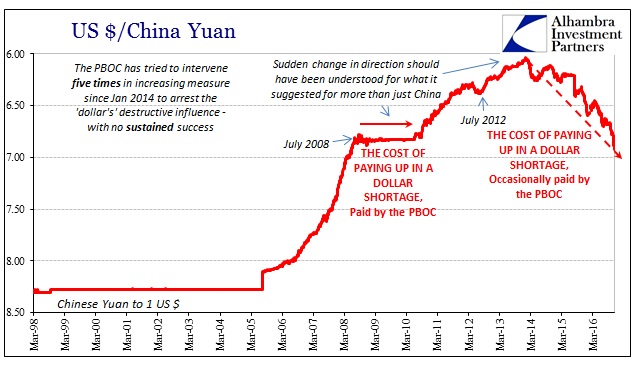

(Click on image to enlarge)

We don’t have to guess what happens when those widely held expectations prove categorically wrong. For the Chinese, that was January 2014. The exact spark of the inflection is unknown or even unknowable, but there were plenty of warning signs in later 2013 including the first hints of corporate defaults as part of China’s “reform” agenda, as well as further innuendo that perhaps the PBOC wouldn’t blindly stand behind everything in China finance. From the perspective of a “dollar” lender, that is increased risk that demands remuneration to be extracted from the now-captured audience (“dollar short”) of China’s corporate sector, including its financial firms acting as “dollar” conduits into China, “paying up” to both borrow additional “dollars” though more so to rollover existing lines.

As is usually the case, when conventional wisdom starts to unwind it does so in snowball fashion; “dollar” lenders demand slightly more premium to reflect a shift in risk perceptions that causes volatility in the exchange rate (especially as it is in the “wrong” direction) that becomes reflected as greater risk demanding even more premium, etc. It is a problem in any environment, but greatly amplified in one where “dollars” overall aren’t plentiful. That was the idea in 2013, so what became the “rising dollar” of 2014 was the inconvenient marriage of that “dollar shortage” with the eurodollar system realizing that it applied to the whole “dollar” coverage, not just DM parts of it and not just in isolated events.

The progression of it for China, as Brazil, was one of increasing alarm and countermeasures; before it became unmanageable in manageable terms. Brazil’s point-of –no-return came much earlier than China’s, but in both cases the result has been the economic consequences of modern, wholesale “money.” The Chinese reflect this reality in several ways, including the accepted idea of “capital outflows” that aren’t really that.

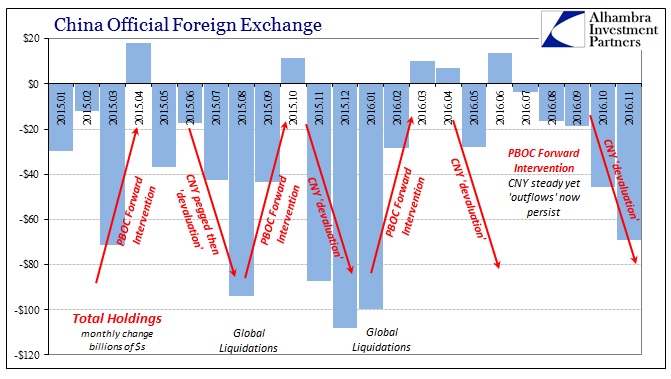

(Click on image to enlarge)

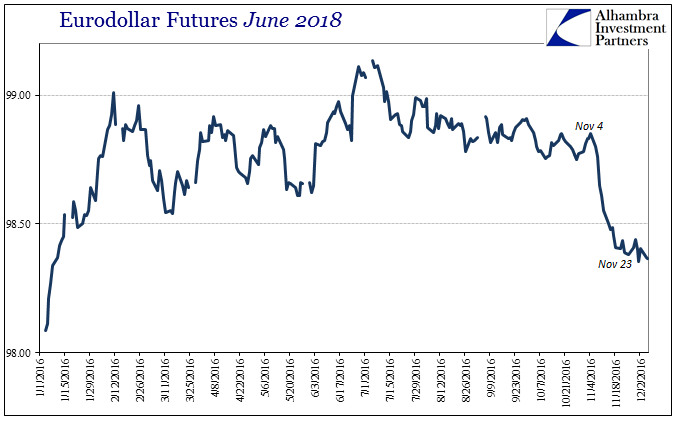

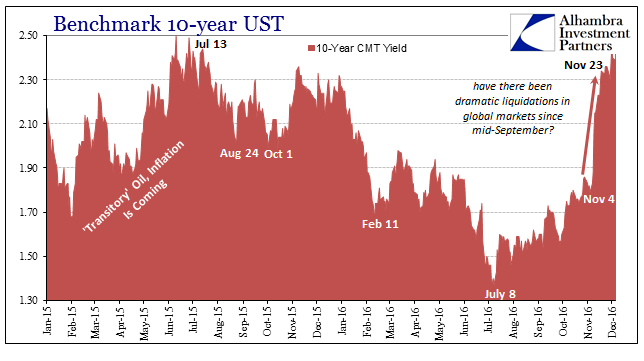

It is therefore no surprise to see that “outflows” have returned with great destructive vigor in October and November 2016. The official, reported monthly figure from SAFE was -$69 billion for the month, the largest by far since January. That follows -$45 billion in October, which begins to suggest conditions more like those from the worst parts of last year, explaining very well the global liquidation that occurred in November that everyone seems to have missed or misconstrued (CNY down = bad, subscription required).

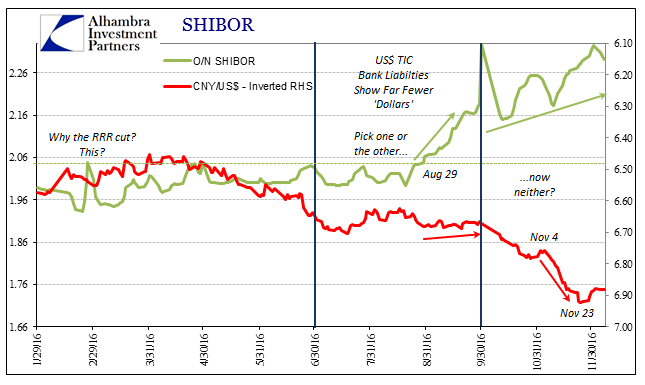

(Click on image to enlarge)

(Click on image to enlarge)

(Click on image to enlarge)

When reported “capital flows” turned positive again for the month of October 2015, after the events of August last year, it was miscomprehended as a sign of confidence coming from the market rather than what it was; artificial interference that put CNY, and thus China and the “dollar”, on the clock. From the FT last November:

Capital flowed into China last month for the first time since an unexpected currency devaluation in August shook investor confidence in the economy, easing fears over financial stability following an unprecedented bout of outflows.

The reason they were fooled into a false interpretation of confidence was that the conventional view is backward.

Outflows accelerated following the central bank’s unexpected move in August to let the renminbi weaken and the main stock index fell more than 40 per cent beginning in late June.

Outflows didn’t cause the RMB “devaluation” because it wasn’t devaluation to begin with; and they weren’t outflows so much as “dollar” withdrawal. The “dollar” problem that had been building since the middle of 2013 had instead caused the PBOC to either support the local Chinese banking sector with its own “dollars” in various forms or to let those Chinese institutions pay up in the private market. Having done the former particularly from March 2015 through early August, the perceived cost (directly as well as indirectly in RMB conditions easily observed by rising SHIBOR) of continuing to “supply dollars” became, we can reasonably assume, far too prohibitive for it to continue; Chinese banks were left to the whims of the eurodollar market all at once on August 10.

Notice that in May, June, and July 2015 there were only reported “outflows” even though the CNY rate was perfectly, and I mean perfectly, steady. The total negative in those three months was nearly $100 billion, which puts into context the nearly $100 billion reported “outflow” in the month of August 2015 alone, as well as the -$69 billion in November 2016.

It is a history of the Chinese central bank trying to manage that which it simply cannot and never will. The best it can do is to try and cope with the disruptions, internal as well as external, even though, per the “ticking clock”, it makes the next one inevitable and that much worse.

Disclosure: This material has been distributed for ...

more