Monetary Tightening Is More Than Just Higher Interest Rates

When Fed Chairman, Jay Powell, hinted that the Fed funds rate was “ just below” the broad range of “neutral”, one could almost hear the collective sigh of relief on Wall Street. It was just about six weeks ago that the Chairman argued that the policy rate was a “long way from neutral”. To many, this new assessment appears that the Fed is nearing the end of its current cycle of rate hikes. Monetary tightening was just about over, or so it seemed.

Financial markets are no different than other markets for goods and services. Evidence of tightening can be found in higher prices --- interest rates, or in supply--- the availability of funds. The stock market seems to latch on to change in interest rates as the measure of the degree of tightening. What is more important is the availability of funds when debating monetary conditions. Investors need to be more concerned with the Federal Reserve’s shrinking balance sheet than with the next ¼ point rate increase.

When the Fed undertook to expand its balance sheet – quantitative easing introduced in 2009 --- it did so to promote greater risk appetite as a means to combat the deflationary effects of the 2008 financial meltdown. Now, the Fed is doing the exact opposite in withdrawing funds from the financial system as it shrinks it balance sheet.

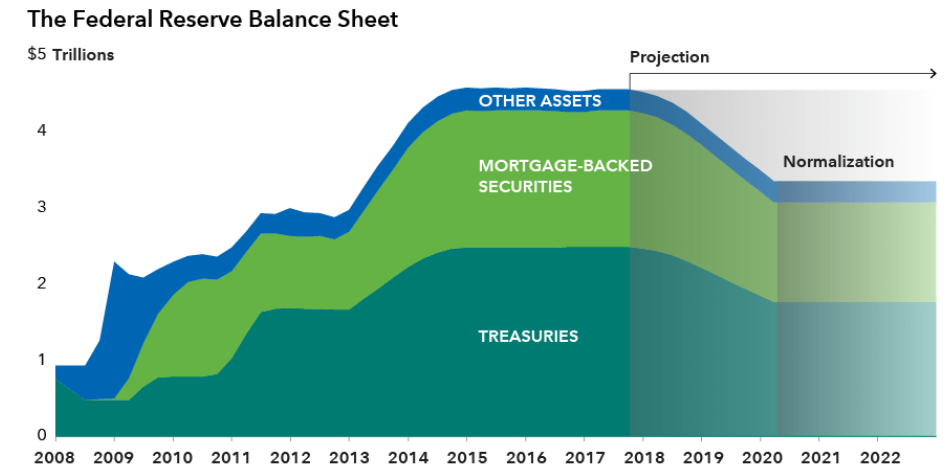

Figure 1 Federal Reserve Balance Sheet

Source: Federal Reserve

The Fed is reducing its balance sheet by $50 billion a month, split roughly 60-40 between Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities, by not re-investing proceeds. The Fed is simply draining the financial system. The Fed’s balance sheet will not likely fall all the way back to its pre-crisis size of $1 trillion. Nonetheless, the Fed will have withdrawn as much as $ 1.5 trillion from the economy once normalization is complete (Figure 1). For those who like to view tightening in terms of rate hikes, this reduction in the Fed’s balance sheet is estimated to equal about a 220 pbs hike in the Fed funds rate.

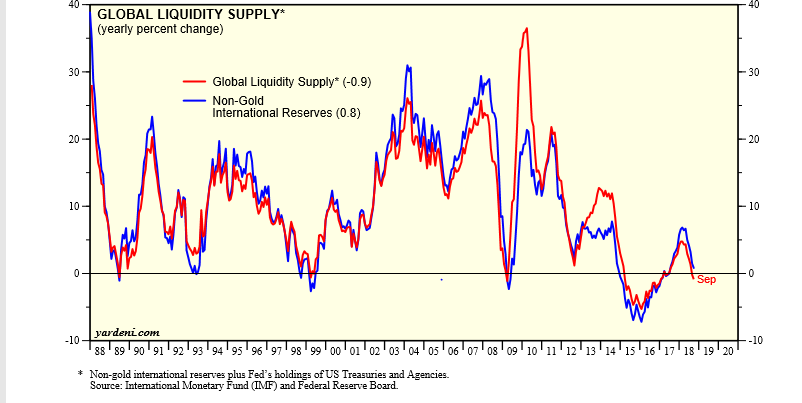

Figure 2 Global Liquidity

Source: Yardeni Research, Inc

Global liquidity, which was expanding at nearly 21 per cent from 2009-2014, has dramatically dropped to virtually zero from 2015 onwards ( Figure 2). This withdrawal is now being felt in financial and commodity markets worldwide. By soaking up liquidity, the Fed is contributing to a slowdown in economic growth which is now reflected in lower oil prices, widening of credit spreads and lower equity prices. When the Fed opened the flood gates during quantitative easing, capital flowed into emerging market economies into both public and private investment. Now, this process has come to halt. The withdrawal of liquidity results in a rising US dollar creating currency problems in emerging economies such as Turkey, Argentina, and South Africa.

Fed is not alone in withdrawing liquidity. The money supply growth --- another way to measure liquidity--- has slowed in Europe and Japan. The ECB has signaled its intent to wind down its bond-buying program, although it is somewhat vague on the starting dates and the amounts.

Although all eyes are on the Fed and its monthly rate decisions, underlying monetary conditions will largely be dictated by the supply of global liquidity.

Market monetarists say NGDP is not falling, yet. Wondering your take, Prof.

Always enjoy a thread between you two!

see my comment to Gary

Since NGDP and real GDP use different inflation measures, they should not be used interchangeably to argue one's case. NGDP can grow because of increases in output and/or prices. Also, the price indices used to calculate NGDP is current prices and for real GDP is constant starting with a specific year in the past. One can pick the measure to suit one's argument.

So, monetarists can take comfort from a higher NGDP but for which reason? Higher output or higher prices?

My real concern is that all the monetary measures that drive an economy are tightening up and this is showing up within important sectors of the economy.For example, here in Canada, mortgage growth is running at 3% annual growth, nominally and housing prices are going up. So, nominal housing is growing. However, if mortgage growth is adjusted for inflation then real credit expansion is zero or maybe negative. The housing market is in trouble because of this.