Links: Housing Bubbles, Trilemma, Policy Timing Uncertainty

Food for thought over the long weekend.

Why Tighten?

I hear a lot about why, despite (by some accounts) a measurable output gap, and low inflation, we need to tighten because of e.g., an incipient housing bubble (or some other unidentified asset bubble). Reuven Glick and Kevin J. Lansing and Daniel Molitor at the SF Fed deal decisively with the leverage-induced housing bubble meme:

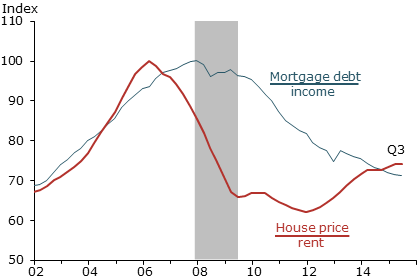

After peaking in 2006, the median U.S. house price fell about 30%, finally hitting bottom in late 2011. Since then, house prices have rebounded strongly and are nearly back to the pre-recession peak. However, conditions in the latest boom appear far less precarious than those in the previous episode. The current run-up exhibits a less-pronounced increase in the house price-to-rent ratio and an outright decline in the household mortgage debt-to-income ratio—a pattern that is not suggestive of a credit-fueled bubble.

Figure 2 from the piece conveys concisely and persuasively their argument.

Source: Glick, Lansing, Molitor (2015).

For me, I remain unconvinced that there is tremendous froth in financial markets thereby validating the case for tightening. At least, it doesn’t appear to be in the housing market.

Tightening Already Underway

I’ve mentioned in an earlier post that the tightening has already begun, and dollar appreciation has in part signalled the reduced rate of Treasury accumulation by foreign central banks that in the past depressed long term yields. These trends are documented in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Fed funds/Shadow Fed funds rate (blue, left scale), log real trade weighted dollar – broad index, 1973M03=0 (red, right scale). NBER defined recession dates shaded gray. Source: Federal Reserve Board, Wu-Xia, NBER, and author’s calculations.

What is going to happen when the Fed actually raises rates? This is an interesting question, which is related to the trilemma. Joe Joyce at Capital Ebbs and Flows contrasts the views of Helene Rey (there’s only a dilemma) vs. those of Klein-Shambaugh, Popper-Mandilaris-Bird, and Aizenman-Chinn-Ito (there’s a trilemma). Professor Joyce sides with exchange rate regimes as still mattering, but re-interprets the Rey thesis:

…But her wider point about the linkages of asset prices driven by capital flows and their impact on domestic credit is surely correct. The relevant trilemma may not be the international monetary one but the financial trilemma proposed by Dirk Schoenmaker of VU University Amsterdam.

In this model, financial policy makers must choose two of the following aspects of a financial system: national policies, financial stability and international banking. National policies over international bankers will not be compatible with financial stability when capital can flow in and out of countries.

I don’t disagree with this view. But I must confess to being of limited imagination, and have a hard time conceiving of an international system that co-ordinates in an enforceable fashion a harmonized and effective system of international financial regulation. In other words, we have to consider policy effects in a world — for now — with regulatorily balkanized financial regulation.

In that context, Joshua Aizenman, Hiro Ito and I have updated our assessment of the impact of core country monetary policies on emerging market economies.

Generally, however, the linkages between developing countries’ exchange market pressure (EMP) and CE’s policy interest rates appear weak. The proportion for the significant linkage rises in the 2010-2012 period, but only to less than 20%. The EMP of developing countries is a little more sensitive to the REER movements of the center economies. The proportion of developing countries for which the center economies’ REER are jointly significant for the EMP estimation is the highest among the vectors of explanatory variables in the 2010-2012 period.

In general, the EMP of developing countries is more exposed to the influence of the center economies’ EMP. Especially, during the GFC years and in their aftermath, developing countries’ EMP is found more sensitive to the movements of the EMP of the CE’s, indicating that financial stress that arose in the CE’s must have been transmitted to developing countries during and after the GFC.

Exchange market pressure is a weighted average of exchange rate depreciation, reserve decumulation and interest rate increase, viz., αΔs + βΔi – γΔr (changes expressed relative to base country). What is the quantitative extent of the impact?

Based on the estimation results, for the group of EMEs, if the U.S. [real effective exchange rate] REER rises (i.e., real appreciation) by 10%, the EMP on average would rise by about 1.2. This (unit-less) figure stands for about 0.6-0.8 standard deviations of major EMEs’ EMP, which is not unsubstantial.

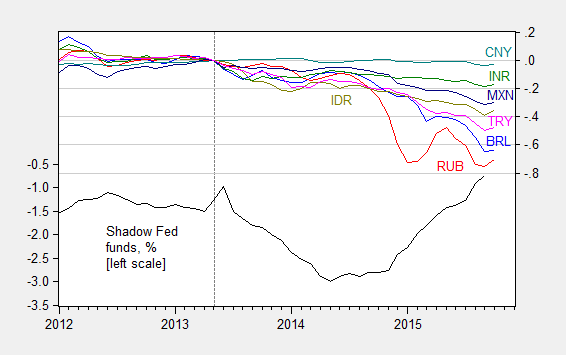

In other words, the US dollar appreciation — in the neighborhood of 15% — is feeding through into elevated exchange market pressure. The components of the EMP are shown for select EMs below.

Figure 2: Shadow Fed funds rate, in % (black, left scale), log exchange rate against USD, where down is depreciation, for Brazil (blue), Russia (red), India (green), China (teal), South Africa (purple), Indonesia (chartreuse), Mexico (dark blue), and Turkey (pink), all normalized to 2013M05=0, right scale. October data is through October 14th. Source: FRED, Wu-Xia, Pacific Exchange Services and author’s calculations.

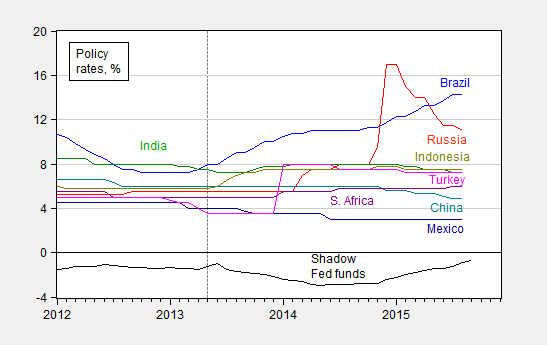

Figure 3: Shadow Fed funds rate (black), policy rates for Brazil (blue), Russia (red), India (green), China (teal), South Africa (purple), Indonesia (chartreuse), Mexico (dark blue), and Turkey (pink). October data is through October 14th. Source: FRED, Wu-Xia, Pacific Exchange Services and author’s calculations.

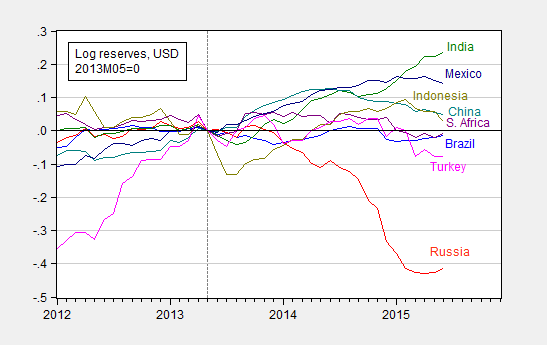

Figure 4: Shadow Fed funds rate (black), and log international reserves ex.-gold for Brazil (blue), Russia (red), India (green), China (teal), South Africa (purple), Indonesia (chartreuse), Mexico (dark blue), and Turkey (pink), all normalized to 2013M05=0. Source: FRED, Wu-Xia, and author’s calculations.

The “Just Get It Over With” Pespective

I’ve been to three conferences over the past month or so involving emerging market central bankers. One common refrain I heard was that it would be better to just get the “liftoff” over with, and resolve the uncertainty. While I think it’s human nature to want to end to act, it seems to me that after the first rate increase, one would immediately start wondering about the timing of the next rate rise.

In other words, an earlier Fed funds rise might be cathartic for emerging market policymakers, but I think their relief might be short-lived.

Disclosure: None.