Eight Insights Based On December 2017 Energy Data

BP recently published energy data through December 31, 2017, in its Statistical Review of World Energy 2018. The following are a few points we observe, looking at the data:

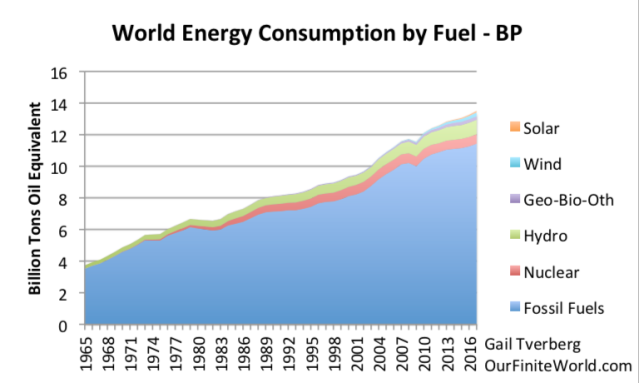

[1] The world is making limited progress toward moving away from fossil fuels.

The two bands that top fossil fuels that are relatively easy to see are nuclear electric power and hydroelectricity. Solar, wind, and “geothermal, biomass, and other” are small quantities at the top that are hard to distinguish.

(Click on image to enlarge)

Wind provided 1.9% of total energy supplies in 2017; solar provided 0.7% of total energy supplies. Fossil fuels provided 85% of energy supplies in 2017. We are moving away from fossil fuels, but not quickly.

Of the 252 million tons of oil equivalent (MTOE) energy consumption added in 2017, wind added 37 MTOE and solar added 26 MTOE. Thus, wind and solar amounted to about 25% of total energy consumption added in 2017. Fossil fuels added 67% of total energy consumption added in 2017, and other categories added the remaining 8%.

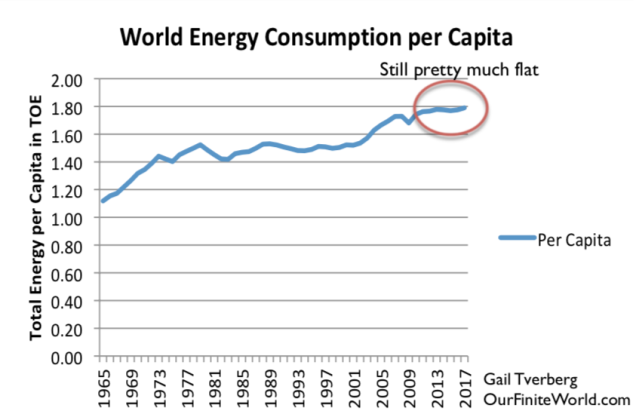

[2] World per capita energy consumption is still on a plateau.

In recent posts, we have remarked that per capita energy consumption seems to be on a plateau. With the addition of data through 2017, this still seems to be the case. The reason why flat energy consumption per capita is concerning is because oil consumption per capita normally rises, based on data since 1820.1 This is explained further in Note 1 at the end of this article. Another reference is my article, The Depression of the 1930s Was an Energy Crisis.

(Click on image to enlarge)

While total energy consumption is up by 2.2%, world population is up by about 1.1%, leading to a situation where energy consumption per capita is rising by about 1.1% per year. This is within the range of normal variation.

One thing that helped energy consumption per capita to rise a bit in 2017 relates to the fact that oil prices were down below the $100+ per barrel range seen in the 2011-2014 period. In addition, the US dollar was relatively low compared to other currencies, making prices more attractive to non-US buyers. Thus, 2017 represented a period of relative affordability of oil to buyers, especially outside the US.

[3] If we view the path of consumption of major fuels, we see that coal follows a much more variable path than oil and natural gas. One reason for the slight upturn in per capita energy consumption noted in [2] is a slight upturn in coal consumption in 2017.

(Click on image to enlarge)

Coal is different from oil and gas, in that it is more of a “drill it as you need it” fuel. In many parts of the world, coal mines have a high ratio of human labor to capital investment. If prices are high enough, coal will be extracted and consumed. If prices are not sufficiently high, coal will be left in the ground and the workers laid off. According to the BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2018, coal prices in 2017 were higher than prices in both 2015 and 2016 in all seven markets for which they provide indications. Typically, prices in 2017 were more than 25% higher than those for 2015 and 2016.

The production of oil and natural gas seems to be less responsive to price fluctuations than coal.2 In part, this has to do with the very substantial upfront investment that needs to be made. It also has to do with the dependence of governments on the high level of tax revenue that they can obtain if oil and gas prices are high. Oil exporters are especially concerned about this issue. All players want to maintain their “share” of the world market. They are reluctant to reduce production, regardless of what prices do in the short term.

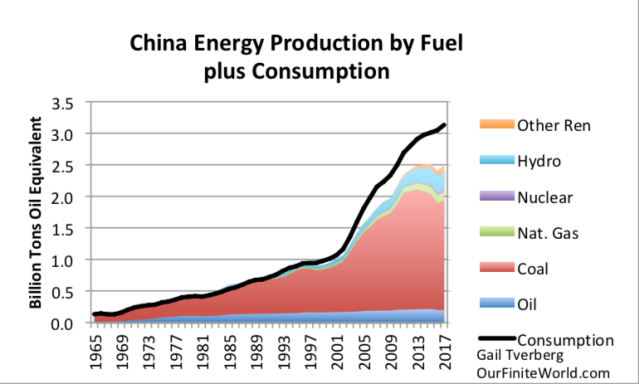

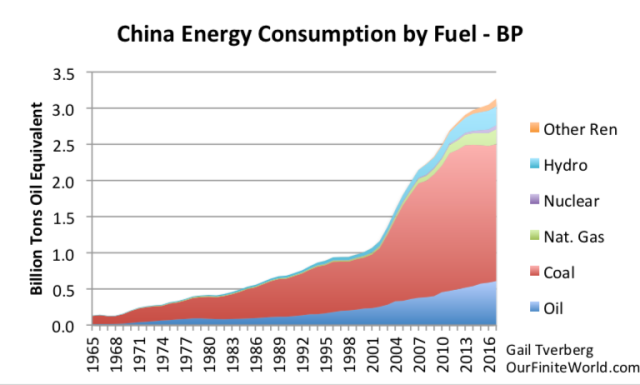

[4] China is one country whose coal production has recently ticked upward in response to higher coal prices. Its overall energy production pattern still appears worrying, however.

(Click on image to enlarge)

China has been able to bridge the gap by using an increasing amount of imported fuels. In fact, according to BP, China was the world’s largest importer of oil and coal in 2017. It was second only to Japan in the quantity of imported natural gas.

(Click on image to enlarge)

If China expects to maintain its high GDP growth ratio as a manufacturing country, it will need to keep its energy consumption growth up. Doing this will require an increasing share of world exports of fossil fuels of all kinds. It is not clear that this is even possible unless other areas can ramp up their production and also add necessary transportation infrastructure.

Oil consumption, in particular, is rising quickly, thanks to rising imports. (Compare Figure 6, below, with Figure 4.)

(Click on image to enlarge)

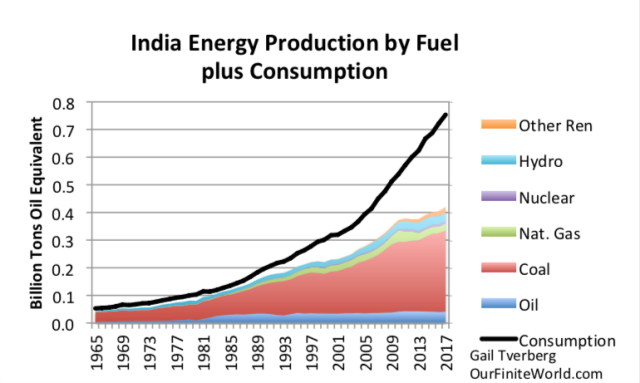

[6] India, like China, seems to be a country whose energy production is falling far behind what is needed to support planned economic growth. In fact, as a percentage, its energy imports are greater than China’s, and the gap is widening each year.

The big gap between energy production and consumption would not be a problem if India could afford to buy these imported fuels, and if it could use these imported fuels to make exports that it could profitably sell to the export market. Unfortunately, this doesn’t seem to be the case.

(Click on image to enlarge)

India’s electricity sector seems to be having major problems recently. The Financial Times reports, “The power sector is at the heart of a wave of corporate defaults that threatens to cripple the financial sector.” While higher coal prices were good for coal producers and helped enable coal imports, the resulting electricity is more expensive than many customers can afford.

[7] It is becoming increasingly clear that proved reserves reported by BP and others provide little useful information.

BP provides reserve data for oil, natural gas, and coal. It also calculates R/P ratios (Reserves/Production) ratios, using reported “proved reserves” and production in the latest year. The purpose of these ratios seems to be to assure readers that there are plenty of years of future production available. Current worldwide average R/P ratios are

- Oil: 50 years

- Natural Gas: 53 years

- Coal: 134 years

The reason for using the R/P ratios is the fact that geologists, including the famous M. King Hubbert, have looked at future energy production based on reserves in a particular area. Thus, geologists seem to depend upon reserve data for their calculations. Why shouldn’t a similar technique work in the aggregate?

For one thing, geologists are looking at particular fields where conditions seem to be right for extraction. They can safely assume that (a) the prices will be high enough, (b) there will be adequate investment capital available and (c) other conditions will be right, including political stability and pollution issues. If we are looking at the situation more generally, the reasons why fossil fuels are not extracted from the ground seem to revolve around (a), (b) and (c), rather than not having enough fossil fuels in the ground.

Let’s look at a couple of examples. China’s coal production dropped in Figure 4 because low prices made coal extraction unprofitable in some fields. There is no hint of that issue in China’s reported R/P ratio for coal of 39.

Although not as dramatic, Figure 4 also shows that China’s oil production has dropped in recent years, during a period when prices have been relatively low. China’s R/P ratio for oil is 18, so it theoretically should have plenty of oil available. China figured out that in some cases, it could import oil more cheaply than it could produce it themselves. As a result, its production has dropped.

In Figure 7, India’s coal production is not rising as rapidly as needed to keep production up. Its R/P ratio for coal is 137. Its oil production has been declining since 2012. Its R/P for oil is shown to be 14.4 years.

Another example is Venezuela. As many people are aware, Venezuela has been having severe economic problems recently. We can see this in its falling oil production and its related falling oil exports and consumption.

(Click on image to enlarge)

Yet Venezuela reports the highest “Proved oil reserves” in the world. Its reported R/P ratio is 394. In fact, its proved reserves increased during 2017, despite its very poor production results. Part of the problem is that proved oil reserves are often not audited amounts, so that proved reserves can be as high as an exporting country wants to make them. Another part of the problem is that price is extremely important in determining which reserves can be extracted and which cannot. Clearly, Venezuela needs much higher prices than have been available recently to make it possible to extract its reserves. Venezuela also seems to have had low production in the 1980s when oil prices were low.

I was one of the co-authors of an academic paper pointing out that oil prices may not rise high enough to extract the resources that seem to be available. It can be found at this link: An Oil Production Forecast for China Considering Economic Limits. The problem is an affordability problem. The wages of manual laborers and other non-elite workers need to be high enough that they can afford to buy the goods and services made by the economy. If there is too much wage disparity, demand tends to fall too low. As a result, prices do not rise to the level that fossil fuel producers need. The limit on fossil fuel extraction may very well be how high prices can rise, rather than the amount of fossil fuels in the ground.

[8] Nuclear power seems to be gradually headed for closure without replacement in many parts of the world. This makes it more difficult to create a low carbon electricity supply.

A chart of nuclear electricity production by part of the world shows the following information:

(Click on image to enlarge)

The peak in nuclear power production took place in 2006. A big step-down in nuclear power generation took place after the Fukushima nuclear power accident in Japan in 2011. Europe now seems to be taking steps toward phasing out its nuclear power plants. If nothing else, new safety standards tend to make nuclear power plants very expensive. The high price makes it too expensive to replace aging nuclear power plants with new plants, at least in the parts of the world where safety standards are considered very important.

In 2017, wind and solar together produced about 59% as much electricity as nuclear power, on a worldwide basis. It would take a major effort simply to replace nuclear with wind and solar. The results would not provide as stable an output level as is currently available, either.

Of course, some countries will go forward with nuclear, in spite of safety concerns. Much of the recent growth in nuclear power has been in China. Countries belonging to the former Soviet Union (FSU) have been adding new nuclear production. Also, Iran is known for its nuclear power program.

Conclusion

We live in challenging times!

Disclosure: None.