Black Monday - 30 Years Between The Monetary Book Ends

This episode happened back in the days before cell phones, and that's what made it all the more unnerving. Your editor was speaking to an audience of nearly 1,000 investors at a Salomon Brothers conference (our then employer) in Boca Raton on the morning of October 19, 1987.

At first, a few people got up from their chairs and walked out, which we thought was quite rude because we had not even gotten to the truly offensive part of our speech!

Then, the auditorium began to buzz noticeably---so we ramped up the volume and speed of our delivery.

At length, half the room was gone and not wishing further humiliation, we finished up quickly and sat down. What remained of the audience then stampeded for the exits.

Soon enough we learned that the stock market was plunging toward its eventual 508 Dow point crash or 22.6% decline. In today's world that would be 5,200 points on the Dow. In one day!

We happened to mention this episode during an appearance on Fox Business this morning (video below) and the hosts rose up in a mighty chorus insisting we were talking ancient history and that "it's a totally different world today".

On that much we could agree, but not in a good way!

So our ruminations today are on how the big picture has changed for the worse, and why the boys and girls and robo-machines still in the casino and still chasing the dip do not see Black Monday 2.0 coming down the pike.

The spoiler alert is that the era of Bubble Finance started the day after the 1987 crash when Greenspan opened up the monetary spigots; and it ended 30 years later in October 2017. That's when the mad money printers at the Fed finally realized they had used up all their dry powder and belatedly launched a new era of balance sheet shrinkage and QT (quantitative tightening), which will drain trillions of cash from the financial system in the years ahead.

It would be more than fair to label these two October developments---separated by three decades---as monetary book-ends.

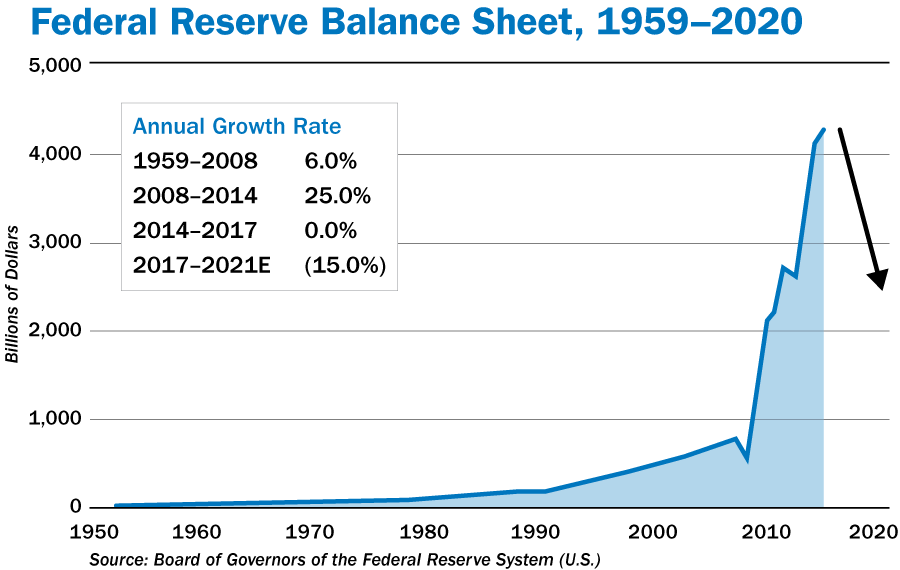

Before Black Monday in October 1987, the Fed's balance sheet had grown only sparingly, more or less in pace with nominal GDP. Indeed, during the first 73 years after opening for business in 1914, the Fed's balance sheet had resembled the classic Ohio State offense: To wit, three yards forward and a cloud of dust, year after year. By October 1987 it stood at just $200 billion.

But after Greenspan succumbed to total panic on Black Monday---and for political reasons, not economics (see below)---- the world changed dramatically. The Fed's balance sheet is now 22X larger at $4.4 trillion, and that massive growth of fiat credit has fueled the greatest inflation of financial assets in recorded history.

As shown in the chart below, especially since the great financial crisis of 2008, the Fed's growth rate has bordered on sheer lunacy. At 25% per annum, credit conjured from thin air has been pumped into the canyons of Wall Street at a rate 7-10 times faster than the real growth capacity of the main street economy.

The result has been not booming profits growth: On the eve of the financial crisis in mid-2007 S&P 500 earnings clocked in at $85 per share. A decade later (June 2017 LTM) they stand at just $104 per share (GAAP basis in both cases). That means the growth rate during the last decade has been a tepid 2.2% per annum in nominal terms, and essentially zero in real terms.

What has soared, of course, is PE multiples, and for the off-stated reason. Namely, the drastic suppression of interest rates that resulted from the massive debt purchases by the Fed and other global central banks caused bond yields to fall to wholly artificial levels. So doing, asset prices were lifted in the equal and opposite direction.

Needless to say, the new era of QT will have just the inverse impact. Since the law of supply and demand has not been repealed-----Wall Street's failure to grasp that truth to the contrary notwithstanding----the sale of trillion of securities by the Fed and other central banks in the years ahead will cause yields to rise significantly.

Indeed, based on its announced plans, one year from now the Fed will be selling bonds at a $600 billion annual rate. Moreover, at some point not too far down the road from that point it will be joined by a cavalcade of additional central bank balance sheet shrinkers. The latter will include the ECB, the BOE, the Bank of Canada, the People Bank of China and, eventually, even the all-time champion money printer of the present era, the BOJ.

None of these central banks will have any choice but to follow the Fed's lead. That's because as it contracts its footings from $4.4 trillion to $2.2 trillion or so there will emerge a massive global shortage of dollars. And a "rising" dollar will force other central banks to shrink their own balance sheets or see their exchange rates collapse and domestic inflation soar.

As we indicated the other day, the world financial system will be shifting from 30 years of the ascending blue line shown below to an unprecedented cycle of the plunging black arrow on the right-hand margin.

We mentioned this in our Fox Business segment this morning, causing our hosts to react with sheer puzzlement. In that regard, they are a proxy for the larger casino in which they operate and a leading indicator of why today's ultra-speculative markets are so unprepared from what comes on the other side of the second monetary bookend.

In this context, it is important to know exactly why the market crashed in October 1987 and to distinguish between the catalyst and the accelerant. The latter, as is generally understood, was a Wall Street scam at the time called "portfolio insurance".

The peddlers of this snake oil essentially said buy the bull market hand-over-fist and don't worry a bit. Just purchase the "insurance" for a small fee and if the market should ever falter, the insurance plan will be selling S&P 500 futures tick-for-tick with any decline in the broad market. Accordingly, you can't lose!

Needless to say, that might well have been true for any single investor, but it could not have been true for the market as a whole. In fact, once the sell-off gained momentum, portfolio insurance became the financial equivalent of kerosene. The more stocks sold off in the cash market in New York, the faster the insurer's sold S&P futures in the trading pits in Chicago. By the end of the day, the S&P 500 future had plunged by a stunning 29%.

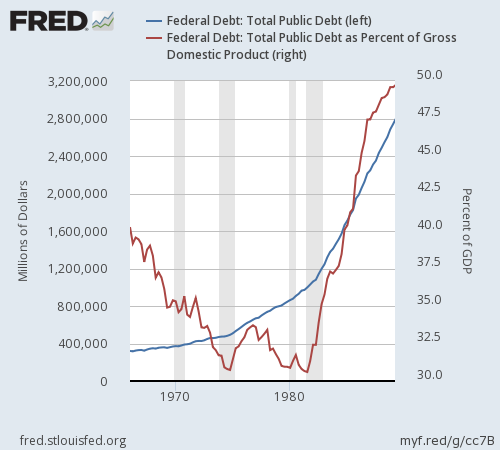

Still, portfolio insurance wasn't the underlying cause. What was actually going on is that bond yields were rising rapidly because the massive Reagan deficits were finally coming home to roost. Private investment was being crowded out and the US economy was being pushed toward recession, and for one historically crucial reason.

To wit, Volcker had been unwilling to monetize the giant Reagan deficits, and that was exactly the right policy. The crowding out effect of Treasury borrowing from a fixed supply of private savings, and the resulting economic contraction and market crash, would have forced the politicians to face up to the fiscal hemorrhage then underway.

Yet it was also a policy which eventually got Volcker fired by the political types in the Reagan White House. The latter bamboozled the Gipper into appointing Greenspan based on sound money/gold standard views that he had abandoned years earlier.

In any event, when Greenspan took over in August 1987. Mr. Market was on the verge of a big correction for valid, fundamental economic reasons. Indeed, on the morning of October 19, 1987 the free market on Wall Street was doing its job, reining in an exuberant market bubble that had gotten way ahead of itself.

At the late August peak of 2700, the Dow was more than triple the mid-1982 recession bottom (800) and, as shown in the chart above, had doubled in just 24 months from September 1985.

To be sure, some sort of stock market recovery from the 1982 bottom was warranted because Volcker had purged the plague of double-digit inflation and the Reagan tax cut of 1981 and reform bill of 1986 had eliminated the growth impediments of high marginal tax rates and the hidden tax of bracket creep.

But by 1987 the explosion of US Treasury borrowing could no longer be contained. At that point, there had been massive tax cuts, a near tripling of the defense budget and very little progress on shirking the domestic welfare state. Indeed, by the time the Gipper left office, domestic spending was still 15.4% of GDP or only a hair below the 15.8% level that had been inherited from big spending Jimmy Carter.

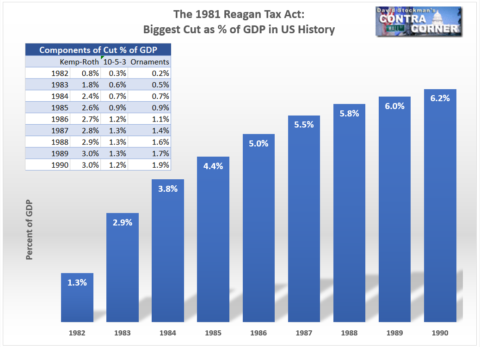

As we have previously explained, the original Reagan tax cut was the result of a bipartisan "bidding war" in the summer of 1981 that had left a massive hole in the Federal revenue base. The latter amounted to 6.2% of GDP when fully effective in the late 198os.

In today's sized economy, for example, it was equivalent to a $1.6 trillion annual revenue reduction by the 10th year---compared to a notional net impact from the Trump/GOP plan of about $230 billion per year by 2027.

In other words, the vaunted Reagan tax cut of 1981 was seven times bigger than what is being proposed now. But it did not spur a sustained boom beyond about six quarters of snap-back rebound from the Volcker monetary vice in 1983-1985.

That's because less than 6% of the resulting Reagan deficits were monetized ($112 billion out of $1.8 trillion). The rest was absorbed in the capital markets which is what eventually resulted in the crowding out private investment and spending.

Here's What A Wild and Crazy Tax Cut Really Looks Like

The chart below tells the rest of the story. Between early 1987 and the October crash, the yield on the benchmark (10-year) Treasury Note soared from 7.0% to north of 10.0%. It was that rapid 45% run-up in yields that eventually triggered the crash.

Needless to say, Greenspan panicked and flooded the market with cash, and also sent his henchman around Wall Street to demand that the major firms keep lending to insolvent customers, rather than liquidate their accounts as was warranted by the financial facts.

So doing, the Maestro short-circuited the market clearing event of October 19, 1987----causing all parties to the game to learn the wrong lesson. Namely, that deficits don't matter in government finance, and that the central bank put will insure ever-rising prices in the Wall Street casino.

The relevance of this history and the profoundly wrong-head lesson of Greenspan's Bubble Finance as they pertain to present conditions will be elaborated upon further in tomorrow's post. But the essence of it is this: The US is once again generating huge full-employment deficits which are expanding rapidly; and once again we have---ironically---a Volcker style central bank unwilling to monetize this outpouring of new Treasury paper.

In a word, its back to the future circa October 16, 1987.

After a 30-year digression in money printing and fraudulent central bank finance of the uncontained Welfare and Warfare States implanted in the Imperial City, the rubber is about to meet the road.

Again.

Disclosure: None.