Avoiding Lost Decades: European Edition

From Liz Alderman in the NY Times today:

Germany and France Aim to Avert a ‘Lost Decade’

The economy ministers of France and Germany called on Thursday for urgent overhauls and a series of investments in both countries to help prevent them and the eurozone from falling into a stagnation trap.

This comes as news of increasing unemployment and falling inflation arrives (from WSJ):

…reports Friday confirmed a grim outlook for much of the eurozone’s $13.2 trillion economy, the world’s second largest after the U.S. Unemployment across the region rose by 60,000 last month, keeping the unemployment rate at 11.5%, the European Union’s statistics agency Eurostat said, far higher than in the U.S. Consumer spending fell in France and Spain.

Eurostat also said consumer prices were just 0.3% higher in the eurozone in November on an annual basis versus 0.4% in October, matching a five-year low. The inflation rate has now been below 1% for 14 straight months, while the ECB targets a rate of just under 2%.

The CEPR/Banca d’Italia eurocoin index also suggests slowing (albeit still positive) growth in the euro area.

Source: eurocoin.

The reference to lost decades reminds me of what Jeffry Frieden and I wrote in Lost Decades:

In the short term, there was no choice but to act decisively, with temporary tax cuts, spending increases, and transfers to the states. And with the economy growing only modestly as recovery began, too rapid a retrenchment in spending and an increase in taxes could very well be counterproductive, throwing the economy back into recession and further accumulation of debt. However, the politics of countercyclical fiscal policy can be perverse, as the Obama administration found. Recessions hit hardest at poor and working-class families, who would benefit most from stimulative fiscal policy. But attempts to undertake these policies face opposition from upper income taxpayers who are less affected by the recession and more concerned about the impact on their future taxes. This opposition can impede an effective fiscal response to cyclical downturns.

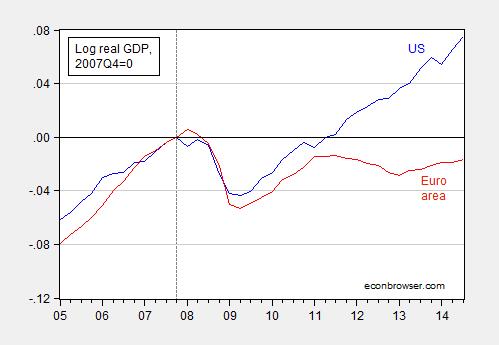

In the case of Europe, part of the reversion to too-rapid fiscal retrenchment was due to German demands for fiscal consolidation, part due to the belief that confidence effects would stabilize debt-to-GDP levels. The impact of relatively expansionary fiscal policy in the US (without hyperinflation so many warned of) as compared to the euro area is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Log US real GDP (blue) and euro area (red).

Source: BEA, and author’s calculations.

For a comparison to the UK, which embarked upon an experiment in expansionary fiscal contraction, only to relent subsequently, see this post. A cross-country comparison is here.

The document referred to in the NY Times article, calling for a “New Deal” and authored by Henrik Enderlein and Jean Pisani-Ferry, is here. They propose:

1. Reforms in both France and Germany. They are not the same, because the two countries are not facing the same challenges. In France, short-term uncertainties reduce long-term trust, but the longer-term outlook looks better. In Germany, longer-term uncertainties reduce short-term trust, but the short-term situation looks relatively good. In France we fear lack of boldness for decisive reforms. In Germany we fear complacency.

2. Reform clusters. Our reform proposals target priority areas where we see urgent need for action in each country. We propose to group actions serving the same aim into ‘clusters’ and to focus on a small number of such clusters. In France, these are (i) the transition to a new growth model, based on a system combining more flexibility with security for employees (“flexicurity”) and a reformed legal system, (ii) a broader basis for competitiveness and (iii) the building of a leaner, more effective state. In Germany, these are (i) the tackling of the demographic challenges, in particular by preparing German society for higher immigration and by increasing female participation in the labour market, (ii) the transition towards a more inclusive growth model based on improved demand and a better balance of savings and investments. Such reforms are not meant to please the respective neighbour, or anybody else, but to create better domestic conditions for jobs, long-term growth, and well-being in each country and in Europe.

3. A European regulatory initiative. Private investment is a judgment about the future. Investments require trust. In many sectors, public regulation plays a major role in the shaping of expectations on the long-term. In energy, transport and the digital sector, to name just a few, regulators must set the parameters right and ensure predictability. Investors need to know with certainty that Europe is committed to accelerating its transition to a digital, low-carbon economy. To lift uncertainty about the future price of carbon or the future regime for data protection is a major responsibility of public authorities. This could significantly contribute to increased investments in Europe.

4. Investment. The well-identified investment shortfall in Germany is largely private. Here again, regulatory clarity and a streamlined legal framework for settling disputes over infrastructure projects have a major role to play to unlock investment. But we also consider that Germany has given itself an incomplete public finances framework that rightly attributes constitutional status to keeping debt under control, but neglects promoting investments within the remaining fiscal space. German assets are not sufficiently renewed. Passing on a worn-down house to future generations is not a responsible way of managing wealth. We think the German government can and should increase public investment. In comparison to other European countries, France does not suffer from an acute aggregate investment shortfall. Business non-residential investment has remained at a relatively high level in comparison to other European countries. The allocation of investment efforts, however, is an area for improvement.

5. European private and public investment boosters. We do not believe that lack of funding is the main obstacle to European investment, but we do consider that new European resources are necessary: in a context where authorities are asking banks to take less risk, it is their responsibility to avoid pervasive risk aversion in the financial system. Building on our regulatory initiative, we propose to inject new European public money into the development of risk-sharing instruments and of vehicles in support of equity investment. Public investment has also been severely reduced since 2007. We propose creating a European grant fund to support public investment in the euro area that would support common aims, strengthen solidarity and promote excellence.

6. Borderless sectors. France and Germany should promote deepened integration in a few industries of strategic importance where regulatory borders severely constrain economic activities. Building “borderless sectors”, together with other partners, involves much more than just agreeing on coordination and joint initiatives: it implies going all the way to a common legislation, a common regulatory rulebook and even a common regulator. We think that energy and the digital economy are such sectors and we also propose a similar initiative to ensure the full portability of skills, social rights and social benefits.

7. Rediscover our common social model. Europe is more than a market, a currency or a budget. It was built around a set of shared values. It is time for France and Germany to join forces to rediscover and reinvent the social model of core Europe, starting with concrete initiatives in the fields of minimum wage standards, labour market policies, retirement and education. In these fields, convergence on the basis of effective joint action is needed to transform the Franco-German space into a true union based on economic integration and shared social values.

Of course, there are reports, and there are reports, and there is no guarantee of implementation. My particular worry I have is that structural reforms proceed without additional spending on infrastructure (or other means of stimulating the economy). Structural reform in the midst of recession is doomed to failure. This is a concern highlighted by Marcel Fratzscher, at DIW, as reported by Bloomberg:

Germany needs to spend more on infrastructure to support high wages that depend on exports of high-quality manufactured goods, Fratzscher said. Finance Minister Wolfgang Schaeuble’s plan for a 10 billion-euro ($12.5 billion) investment boost starting in 2016 is too little and came late, he said.

While Fratzscher said policy makers aren’t focusing enough on the risk of financial or political shocks in the euro area reigniting the crisis, Merkel regularly says it’s too early for Europe to relax fiscal rigor and that balancing the budget will help future generations.

“We need decisive action in overcoming the sovereign debt crisis,” she said in a speech in Berlin two days ago. “We have it under control, but we haven’t overcome it yet.”

Germany’s balanced-budget plan is “a fatal signal,” Fratzscher said. “It says: we don’t care what’s happening to the economy.”

Disclosure: None.