Another New Year, Another Set Of Forecasts Of Higher Inflation And Higher Bond Yields

The new year was ushered in with bonds selling off and all attention turned to the anticipated increase in central bank rates. The Federal Reserve has signaled that it intends to continue to raise the Fed funds rate in its quest for normalization. Reports out of the ECB are calling for the unwinding of its large QE program and hinting at possible slight upward adjustments in its bank rates. Although the Bank of Japan has not signaled any change in policy, a slight uptick in growth and inflation has traders on the alert for possible changes in BOJ’s stance away zero interest rates.

The call for rate increases takes the following reasoning: worldwide, global growth is steady, if not solid; in the United States, the tax reform will boost growth, unemployment will fall further, labor markets will tighten up and, ultimately, inflation will accelerate to 2% or beyond.

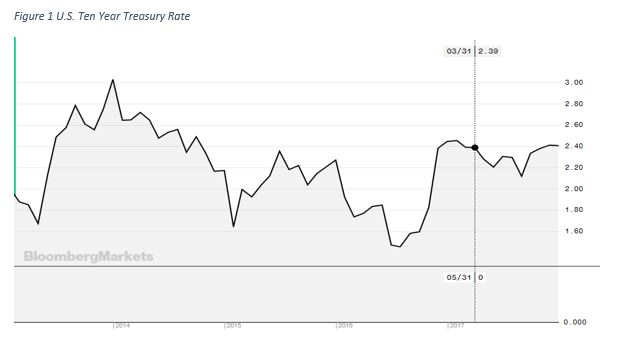

Wall Street analysts are telling clients that 10yr bond will end the year in the range of 3% or better, a level not reached since 2014.

Everything in the bond market hinges on current and, more importantly, expected inflation. Herein, lies the big issue, since inflationary expectations have failed consistently over the decade to materialize. On this subject, there have been some very insightful analysis on why central banks continue to hold dear to their inflation targets.

Bradford Delong challenges the many assumptions that underlie conventional wisdom about inflation.[1] He starts out with the most important assumption. He argues “interpreting today’s low inflation as a symptom of temporary supply-side shocks will most likely prove to be a mistake”. In previous blogs, I have argued the case that the disinflation is not “transitory” in many sectors[2]. The technological changes we are witnessing in our daily lives, e.g. supply chain efficiencies, are here to stay.

Delong argues that central bankers operate under on “a fundamentally flawed assumption about the primary driver of inflation in the global economy since World War II”.After nearly 20 years of observations, it is clear that the Phillips curve is no longer a harbinger of inflation. No longer can we expect that increases in aggregate demand above levels consistent with full employment will have a substantial impact on inflation. Delong takes to task “those who have used the prevailing economic fable about the 1970s to predict upward outbreaks of inflation in the 1990s, the 2000s, and now the 2010s have all been proven wrong.” Yet, central bankers continue to hold on this belief that unemployment rates are inversely related to inflation rates.

As long as central bankers adhere to the view that inflation will pick up—it is just a matter of time—conventional forecasts will call for a rise in bond yields and a return to “normal” levels.

[1] Why Low Inflation Is No Surprise

[2] A Funny Thing Is Happening On The Way To Rate Normalization and The Digital World Challenges Central Bankers

Disclosure: None.