The Story Of Shipping Is Our Economic Story

There was a lot of talk about the supposed oil supply glut around early 2015, for good reasons that only partially related to the supply of oil. That wasn’t the only industry impacted by what was really going on, meaning the falling demand side to the world economy. Shipping companies have faced a supply glut of their own, but one that stretches much further back than the “rising dollar.”

In the middle of the last decade, shippers went nuts though they believed they were being prudent. Global trade was soaring on the winds of eurodollar expansion moving productive capacity all over the world, though concentrated to a good degree around China and Asia. Globalization was a boon to those who could move goods in size because it meant so many goods (and resources) would have to be moved.

In 2007, an astounding 2,905 ships greater than 20,000 tons were ordered from the world’s shipbuilders. US imports from China were growing steadily by 20% at the time, whereas Chinese exports overall were expanding by 30%. Conventional wisdom suggested that goods carriers should expect 2.2 to 2.5x global GDP in terms of trade growth. Clear sailing on that account was widely forecast even as that little subprime problem popped up (economists, echoing Bernanke, said it was all contained)..

The world economy, of course, collapsed in late 2008 which put a temporary halt on shipbuilding. Orders for the same size big ships fell to 1,874 that year, and then just 580 in 2009. The damage, however, was already done and a supply glut of shipboard capacity born.

The price charged for a typical capsize vessel reached $230k per day in 2008, an impressive $180k per for crude oil tankers. By 2012, capsize costs were just $5k per day since so many new ships ordered in that late growth period (2006-08) started to come online. But like the oil story, the world’s shipping context is dominated by the demand side, not supply.

For one thing, despite so many ships being floated in the early “recovery” period most if not all believed it was actually a recovery period. Though they might have to absorb losses, maybe even heavy ones, shippers battened down the hatches and began to wait for demand to catch up. It was, everyone was told, merely a matter of time.

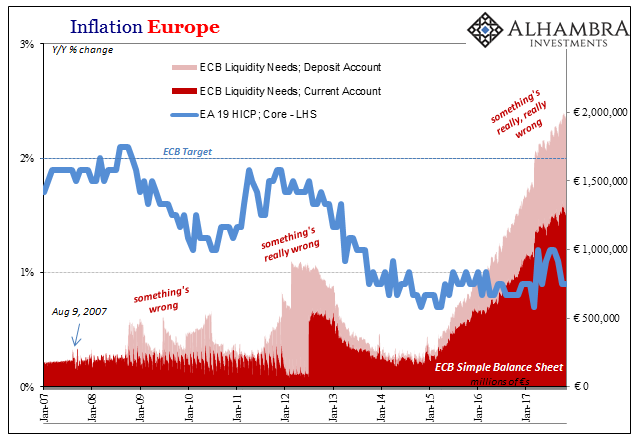

By 2012, as prices plummeted, it had become clear that time wasn’t 2012. Europe had dropped into re-recession and as a major trade hub due to its demand for goods, that really hampered the anticipated rebound. Then the US economy slowed, too, reaching nearly recession later in that year (panicking the Federal Reserve into a third then a fourth QE to try to stave off outright demand disaster).

Fitch ratings assessing in 2012 a whole lot of debt being issued by shipping companies related to both the order glut of new ships as well as the losses being piled up as prices dropped further, decided that it would take a few more years still before equilibrium might finally be reached.

Fitch expects industry overcapacity to continue until 2014, when increased scrapping rates, reduced ship order books and an improvement in global demand should bring the market closer to equilibrium. [emphasis added]

The world was waiting for that “improvement in global demand”, such that it is always, always promised but never materializes. That one didn’t, either, as global trade starting in 2014 failed to live up to expectations…and then suddenly plummeted in 2015.

Several companies, however, were betting quite differently. AP Moller-Maersk (AMKAF) ordered 20 massive ships able to carry 18,000 containers (up from 14,000 that was standard) at a single voyage in 2011. The other major carriers followed Maersk toward the abyss on the assurances of people like Ben Bernanke and his QE’s.

In September last year, Korean shipper Hanjin Shipping was the one to finally fall in. The first major shipper to hit bankruptcy since 1986, Hanjin had given up management control last April to Korea Development Bank, missed supplier payments in July, finally petitioning a Korean court for protection at the end of last August. That court ruled in February 2017 the company was actually worth more in liquidation than as a going concern.

The judgment seemingly flew in the face of conventional wisdom which remains steady to the global growth scenario. It’s still coming, they say, they being economists and central bankers (redundant), only it’s been delayed time and again by “transitory” factors. Shipbuilders and shippers themselves who were once eager to believe them really haven’t been the past few years.

“There’s been no large container ship orders since 2015 and owners are showing restraint,” says [Jonathan Roach, a container shipping analyst at shipbroker Braemar], adding that shipping lines simply haven’t needed new vessels. This fall in orders has also contributed to a number of bankruptcies in shipbuilders who had in some cases been left holding cancelled vessels.

“Container rates are finally beginning to rise and this year has been better than last,” adds Roach. “But then you look back at last year and realise it was just terrible with no growth at all.”

That’s been the one hope of not just the shipping industry but for all parts of the global economy. “Reflation” hit ship rates as well as bond yields and certain economic statistics (even the IMF became so bold as to raise its estimates for global trade this year). There was some cautious optimism that it might hold this time. The Baltic Dry Index, for example, which registered an all-time low the week of February 11, 2016 (the bottom for a whole lot of things) at $291 has risen to $1,727 recently, having had a pretty good run with oil since July.

But there is growing sense that this one might not be real, either. Maersk reported this week that it is seeing some warning signs out in front.

The world’s largest container shipping line says international freight rates are reversing after climbing for most of this year, raising questions about the sustainability of the global trade recovery.

Unlike economists, they would know given their direct experience of the dangers involved with listening to economists (2007, 2011, and again in 2015). For as much as things generally might seem better this year compared certainly to last year, “something” is still missing. Global growth, including the backdrop of trade growth, appears to remain elusive, more what “should” happen than (ever) does.

Disclosure: None.