It Was Never Numbers

Just over a week ago, the world (at least in chemistry) celebrated Mole Day. Rather than acknowledge the small underground mammal that immediately springs to mind, Mole Day is in honor of Amadeo Avogadro, the Count of Quaregna and Cerreto, who lived in the late 18th and early 19th centuries and contributed one of the major international base units in use today. Known as Avogadro’s Number, the Count figured that there is a constant number of constituent atoms or molecules contained in a given mass. The unit is denoted as one mole, thus Mole Day, and the number of individual units within one mole is always 6.022140857×10^23.

While Mole Day is intended to increase attention and interest in chemistry by a dazzling display of such big numbers, our human minds remain incapable of absorbing them. We are hardwired for our own visceral existence, of what we can perceive in front of us. Our brains deal with small numbers in accurate representations, while those beyond certain thresholds become abstractions or at best approximations.

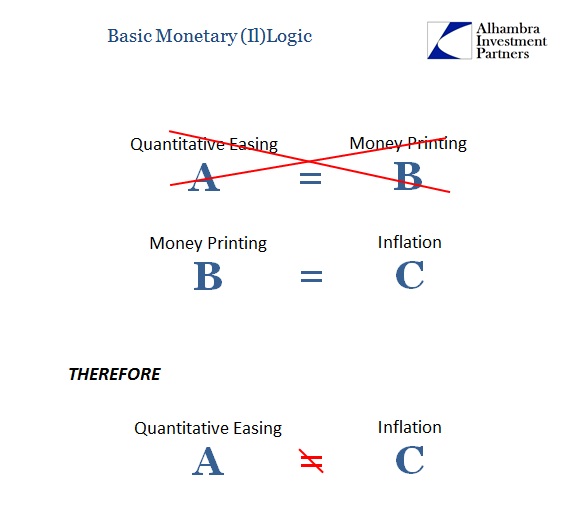

It was this fact of life which drove central bankers especially in Japan toward massive “quantitative easing.” Because we can only conceive of something like trillions as an intangible concept, it was meant to be just so shocking. Though we cannot actually appreciate the precise difference between trillions and, say, billions, we do know there is one and that it is indescribably large even if unsure of exactly what that means.

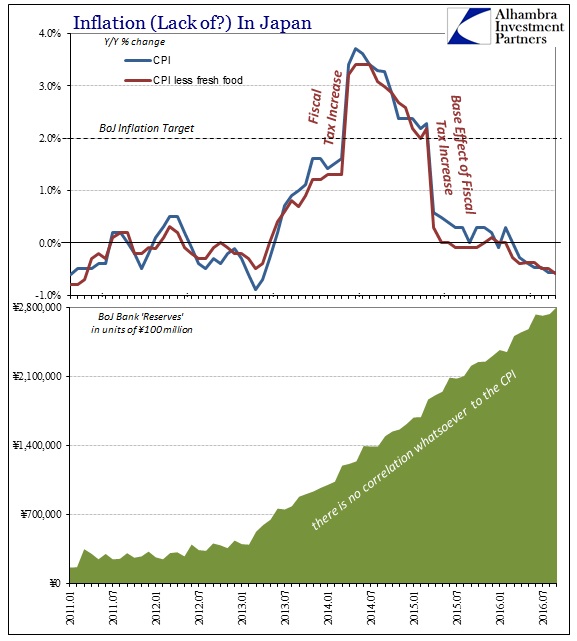

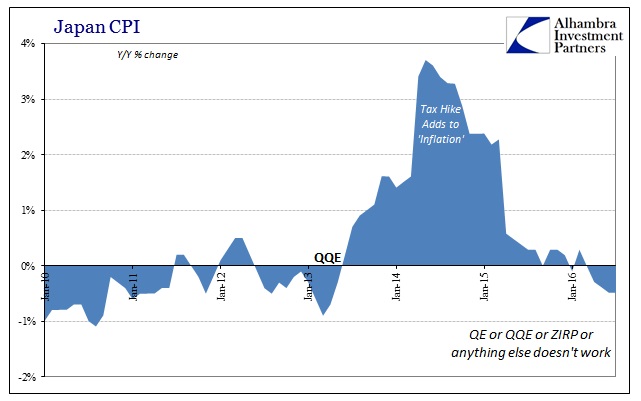

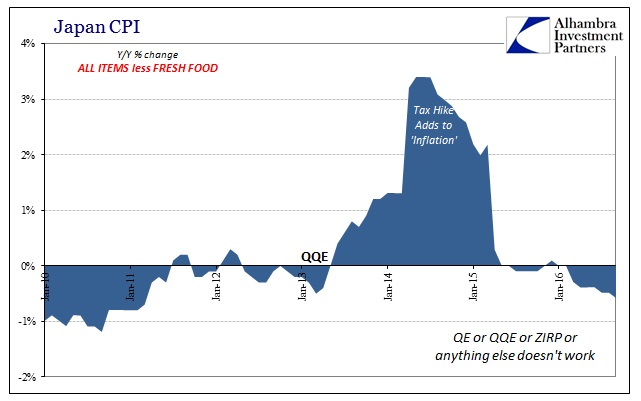

For QQE in Japan, these big numbers were meant for exactly that kind of shock. So large was the “money printing” that investors, businesses, or Japanese households would have no choice but to act as if truly unthinkable “money printing” was the future, sustained course. And the numbers bear out that threat, as the latest update (through September 2016) to the BoJ numbers show ¥280.35 trillion in bank reserves. That is an increase of ¥227.7 trillion since QQE began; a 433% balance sheet expansion from one that was already greatly expanded.

Yet, for those hundreds of trillions of yen far beyond any possible understanding, there remains in 2016 no trace of them where it actually counts. Maybe the “quantity” part of QQE just got to be too big so that it was distilled by economic agents as truly ridiculous. Or maybe bank reserves just aren’t money, and therefore no matter how many were created it didn’t actually matter.

It is impossible to come to any other conclusion, a hardened interpretation that, ironically, these huge numbers prove without reservation or doubt. Because the amount of bank reserves was so unbelievably large, it is impossible to contend that the QQE program was, as is always claimed in these QE failures, just not big enough. Rather than shocking the Japanese people into inflation subservience, the BoJ instead substantiated itself as inept and incompetent no matter how many of these yen.

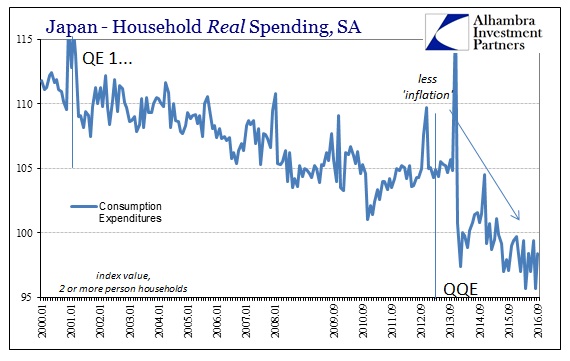

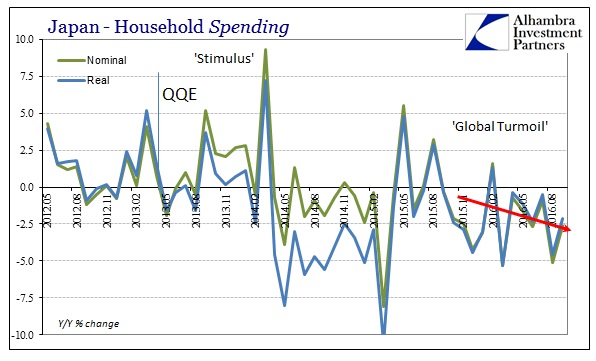

As is also always the case, that isn’t the end of the story. The Japanese people have had to bear the unimaginably huge brunt of depression, where the brief surge in prices (far more related to taxes than bank reserves) caused but amplification in their misery. In what can only be characterized as small mercy, it is the only positive here where the Bank of Japan has so flunked in its large number mission. The return of “deflation” has been obvious in its defeat for BoJ but also some relief from those who suffered the experiment.

The CPI fell by an increasingly negative rate, overall -0.58% in September from 0.0% as late as March 2016. Though the decelerations and negatives were initially blamed on oil, that is clearly not the case now, suggesting that it never was. The Japanese are beset by, again, depression rather than commodity prices in either direction. Since the BoJ has been at this for more than a quarter century now, that fact would easily solve the “riddle” as to why the Japanese may not have been so impressed by an order of magnitude (or two) more “easing.” They appreciate on an individual level the huge difference between actual and theoretical stimulus.

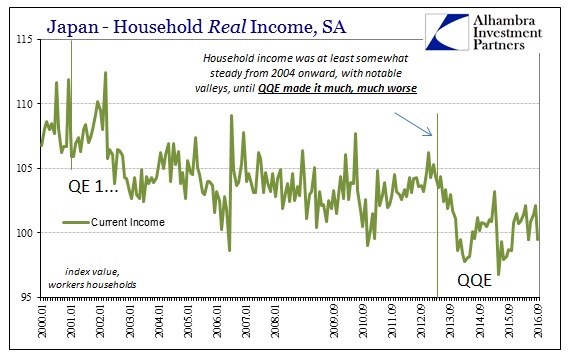

Though household income has been better of late, that, too, is relatively meaningless as we here in the US also cannot conceive of where Real Household Income could possibly be nearly 4% less in September 2016 than March 2013. Though it is a small number, it escapes our own personal experience, leaving us to commiserate not in exactly the degree of depression but in overall awareness that no matter the actual number that is what all this truly is (globally).

Where Japanese incomes fall, spending contracts that much more. Real Household spending was down another 2.1% in September (-2.6% in nominal terms) after falling 4.6% in August. Since QQE started three and a half years earlier, real spending is down almost 6% total. As much as that number represents a truly unfathomable dreadfulness, it is the three plus years that is the greatest cost, added to the decades already lost and social destruction already wrought.

Economists, however, are stubborn because of their ironclad devotion to their own ideology above all else. QQE was, quite frankly, blatantly stupid to begin with, not some genius or courageous expansion that would “solve” a size problem that policymakers themselves dreamed up to “explain” all past failures – and there have only been failures. An objective view of Japan’s situation needn’t have wasted so much time and distortions from hundreds of trillions in non-monetary yen.

With economists so dedicated in their enthusiasm for their own ideas, it instead takes this much time and being left with no other interpretation for them to finally give up on what was never going to be successful. That is why QQE was last expanded (ridiculously) at the end of October 2014 (as if that would offset the “rising dollar” that was/is actually monetary in its global economic effect), leaving the BoJ to consider this year increasingly absurd but alternative ideas. Having been forced to learn about numbers, the central bank is reaching now for qualitative illusions. As I wrote last week:

In Japan, the JGB curve had flattened to an almost perfect straight line; the 2s10s had dropped to a low of just 5.6 bps on July 6. By mid-September, however, the JGB curve had steepened back out to 25.3 bps, and with the recent pronouncement for “yield curve targeting” the JGB 10s have steadied and the curve spread sticking to around 20 bps. Does that count for more successful “stimulus?” The answer might be clearer had these spreads been calculated on a curve where both ends were actually positive. In other words, when the JGB curve was at its flattest it was because the 10-year bond had fallen in “yield” to a ridiculous -27.8 bps, as compared to -33.4 bps “yield” for the 2s. As of the latest close, the curve has “steepened” to where the 10s are back at -6.4 bps “yield” and the 2s -25.4 bps.

The BoJ actually purchased fewer 10s in their last September operation than they had been purchasing in those that came before. I have no doubt that the governing council is congratulating itself on such good execution of its new strategy if only because they truly don’t know from any realistic standpoint what that strategy actually is. They set out in QQE to buy a whole lot of 10s as if that was what Japan needed; then they decided three year and a half years later they bought too many 10s, and cut back because that is what Japan needs. Maybe what Japan needs is none of this?

That last bit is the option that economists will never consider because it is the one that doesn’t include them. They would rather try to “fix” a never-ending depression than to allow an actual recovery. The worst part is, however, that because they had been so successful at convincing the Japanese people (and this is not strictly a Japanese condition) that all of this is so complex and beyond personal experience there is or ever will be no other choice. And so they, as we, remain in depression because the concept of economy has been distorted as if it was some unthinkably large numbers rather than what it had always been before – the easy to understand sum of all personal experience.

Disclosure: This material has been distributed for ...

more