China’s Tetralemma

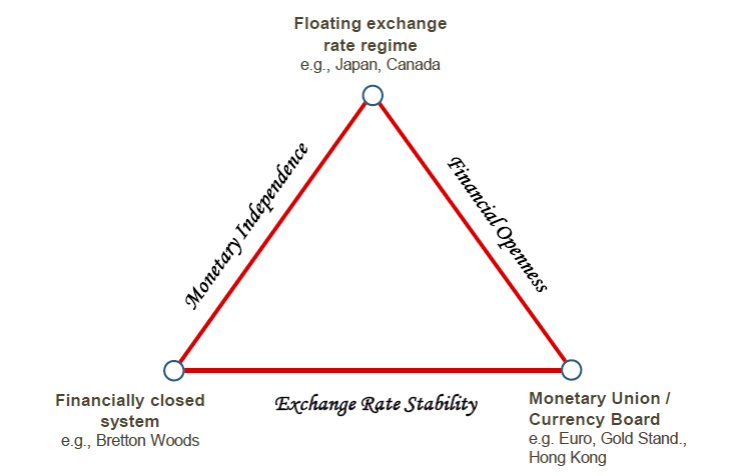

Many countries have three policy objectives: (1) being able to set their own monetary policy, in order to keep their own inflation and unemployment at desired levels; (2) having a stable exchange rate, in order to avoid disruptive shifts in exports or imports; and (3) allowing free capital flows, in order to help the country’s citizens and firms find the most efficient sources and uses of capital. But the famous policy trilemma of international economics claims that any country is going to be forced to give up on one of those three goals.

Source: Aizenman and Ito (2013).

Exchange rate stability has always been a key priority for China. The policy objective they gave up to achieve this was the right leg of the above triangle. China’s current capital controls include limits on the ability of Chinese residents to convert yuan into foreign currency and restrictions on cross-border financial transactions.

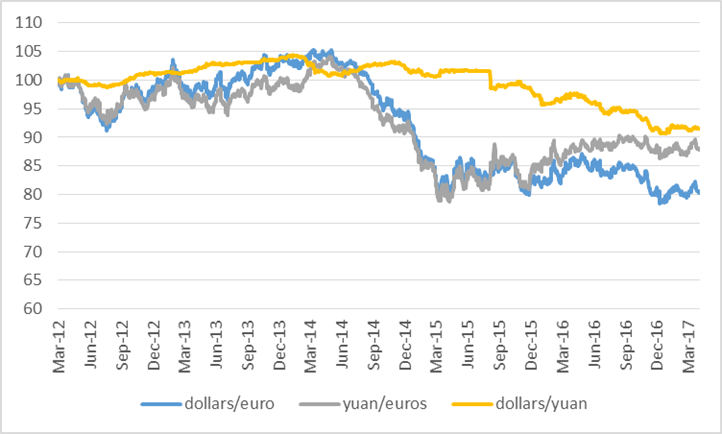

But within that bottom leg of the triangle there is itself a separate dilemma– with which currency does China seek a stable exchange rate? If the ultimate policy objective is stable exports, the answer would be stability with respect to the currencies of China’s major trading partners. But over the last few years, the euro has plunged against the dollar. The U.S. and Europe pursued very different monetary policies, with Europe pushing deeper into negative interest rates even as the U.S. began another cycle of rate hikes.

Number of U.S. dollars needed to buy one euro, normalized at 100 for March 5, 2012, daily from March 5, 2012 to April 7, 2017. Data source: FRED.

On the other hand, China’s yuan stayed with the dollar through most of 2015.

Number of U.S. dollars needed to buy one euro and number of U.S. dollars needed to buy one yuan, both normalized at 100 for March 5, 2012, daily from March 5, 2012 to April 7, 2017. Data source: FRED.

But that meant that the yuan, like the dollar, appreciated tremendously against the euro, which put a drag on Chinese exports to Europe. Since 2015 the yuan has depreciated against the dollar, splitting the difference. The yuan today is down about 9% against the dollar and up 12% against the euro compared to five years ago.

Number of U.S. dollars needed to buy one euro, number of U.S. dollars needed to buy one yuan, and number of Chinese yuan needed to buy one euro, all normalized at 100 for March 5, 2012, daily from March 5, 2012 to April 7, 2017.

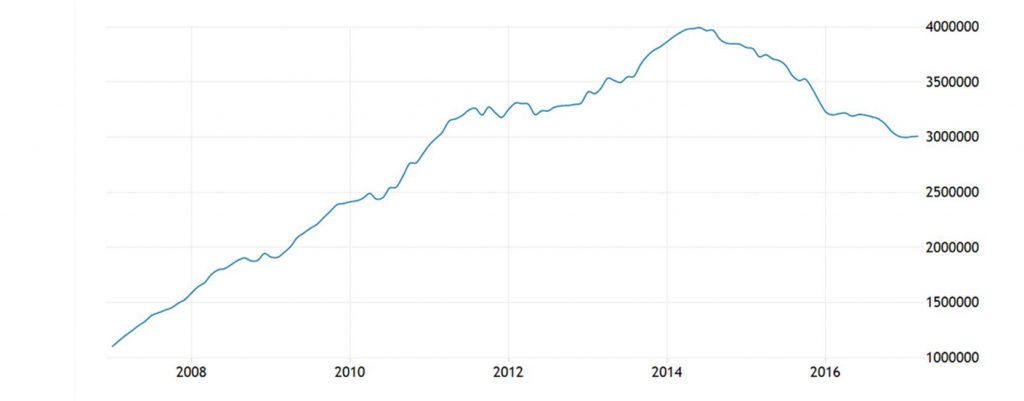

One tool that China has historically used to stabilize the exchange rate is direct purchases by the Chinese government of assets denominated in foreign currencies. China had accumulated 4 trillion dollars’ worth of foreign reserves as of the start of 2014. Purchases by China of U.S. dollars could have been a factor keeping the yuan cheap relative to the dollar during that period.

China foreign currency reserves in millions of U.S. dollars, April 2007 to April 2017. Source: Trading Economics.

But since then there has been a trillion-dollar outflow, as China sold huge holdings of foreign assets. The presumption is that the depreciation of the yuan against the dollar would have been even sharper in the absence of these sales. Since 2014 China has been acting like a country trying to keep its currency up, not a country trying to keep its currency artificially depressed. China’s leaders may fear that allowing the yuan to fall more rapidly against the dollar could undermine confidence in the government and make it harder for Chinese firms to pay back dollar-denominated debts.

I therefore welcomed news that President Trump has backed away from his earlier insistence that China is currently engaging in policies that keep its currency artificially cheap. See also Menzie’s excellent analysis.

Disclosure: None.