Brexit Uncertainty Is Already Affecting Investment And Location Decisions

“It is a truth universally acknowledged that business abhors uncertainty, and nothing is more uncertain than Brexit… Bank of America (BOA) has picked Dublin as its main base for EU investment banking and market operation after Brexit…Japanese Banks, such as Nomura and Daiwa, have said that they intend to make Frankfurt the main base for EU clients… Everyone is planning on a hard Brexit” (The Economist, Brexit Contingency Planning, August 15, 2017)

Under the agreed timetable, the Brexit decision to take Britain completely out of the European Union, is scheduled to take full effect in March 2019.

Ironically, until last year the Brexit Leave vote did not materially affect the British economy. Prompt interest rate cuts by the Bank of England and the devaluation of the pound helped stem any early negative effects. Unfortunately, the early positive gains from the Bank Of England’s actions seem to have run their course, and the British economy is already slowing down.

International firms doing business in both the UK and the EU have been making contingency plans and it comes as no surprise that this kind of planning is already imposing a crimp on investment spending and economic growth in the UK.

Indeed, as Barry Eichengreen points out (Revenge of the Experts, Project Syndicate, August 19, 2017), crises sometimes take time to develop, but when they surface (think of the recent Great Recession) they hit quickly and massively.

Based on the tight timetable for negotiations, we still have no idea whether from the UK perspective the final agreement will end up as a soft or a hard Brexit arrangement.

Of course, the City of London, the financial center of the EU, is particularly vulnerable to the Brexit outcome, whether hard or soft. The banks which are centered in London could potentially lose a great deal from a hard Brexit, since they are very dependent on passport rights and EU regulations.

While the vote to leave the EU was clearly influenced by immigration concerns, there should be no doubt that many British interpreted the Leave decision as a vote to regain UK sovereignty from the EU.

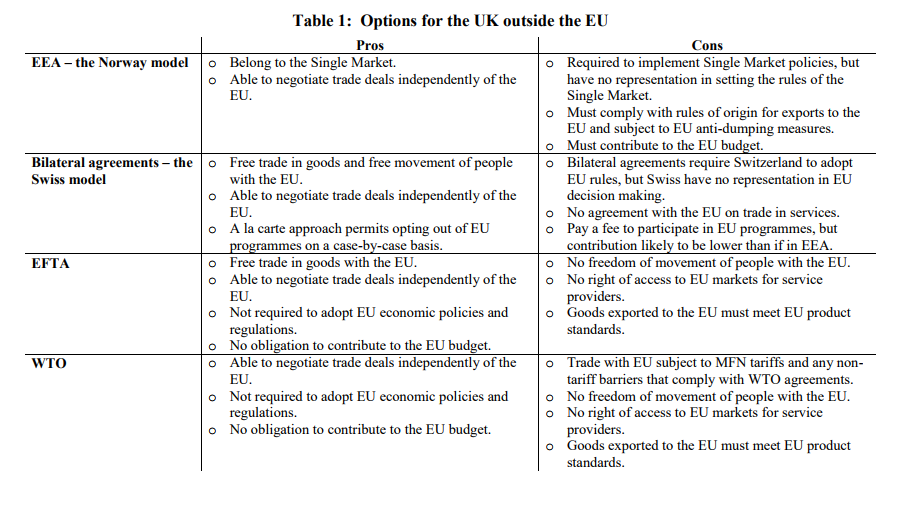

As Swati Dhingra and Thomas Sampson recently observed in a report prepared for the Center for Economic Performance, there are many issues to be resolved in the Brexit negotiations. How the issues could be resolved are discussed below and summarized in the following table.

First, what happens to the UK businesses and the two million UK citizens that are resident in the EU? And what happens to the EU businesses and the three million EU citizens that are resident in the UK?

For example, would Britons living or working in the EU retain the same rights that they currently enjoy, or would they be treated like migrants from outside the EU? Will migrants from the EU have the right to stay in the UK?

Then there are the issues related to what kind of trade, migration and people model might be signed?

Could a new agreement be similar the Norwegian/ EEA model which would have the UK paying about 83% as much into the EU budget as the UK currently does? It would also require keeping current EU regulations (without having a seat at the table when the rules are decided). If a Norwegian type of model was negotiated, it would have the least onerous trade and investment effects on the UK economy. The UK would still have easy access to the European Market, but there would also be free movement of goods, services, people and capital within the EEA. In other words, from a sovereignty perspective, the UK would still have to implement EU rules concerning the Single Market, including legislation regarding employment, consumer protection, environmental and competition policy.

Then there is the Swiss model to consider. Switzerland is not a member of the EU or the EEA. Instead, it has negotiated a series of bilateral treaties on specific subjects with the EU. Each separate treaty provides Switzerland with the right to participate in a specific EU policy or programme. Switzerland still faces regulation without representation and pays about 40% as much as the UK to be part of the single market in goods. As well, the Swiss have no agreement with the EU on free trade in services, an area where the UK is a major exporter. Adopting the Swiss model of Brexit would be appealing to the UK if it wants an ‘à la carte’ approach to European integration. (This is also regarded as a relatively soft option)

The UK could also re-join the European Free Trade Association, which is a free trade area covering all non-agricultural goods. EFTA also has free trade agreements with the EU and numerous other countries. Re-joining the EFTA would guarantee UK goods tariff-free access to the EU and would ensure that the UK did not impose tariffs on goods imported from the EU. But it would not provide for free movement of people or free trade in services between the UK and the EU. Dhingra and Sampson conclude that re-joining EFTA is not an appropriate stand-alone solution for the UK following a Brexit.

A hard Brexit option would have the UK simply becoming a sovereign member of the World Trade Organization. This would provide the UK with the most sovereignty at the price of less trade and the largest fall in income, even if the UK were to completely abolish all tariffs.

The pros and cons of the four potential models are set out below in the following table.

Source: Swati Dhingra and Thomas Sampson, Life after BREXIT: What are the UK’s options outside the European Union? Center for Economic Performance, On the Web.

Disclosure: None.