Blaming The Boom Basis

Once the sick man of the global economy, Europe’s system had roared back in 2017. According to the narrative, everything is right right now on the Continent. Manufacturing couldn’t possibly be any better, and the ECB forced into “emergency” monetary measures for longer than almost anyone else (except, as always, Japan) is talking confidently about winding everything down.

We are told the concern there is more about overheating than any further weakness. Europe is, in short, booming.

Or is it?

The basis for the assertion is especially thin upon examination. Instead, the condition is purported on the strength of rather dubious measures and carefully orchestrated observations.

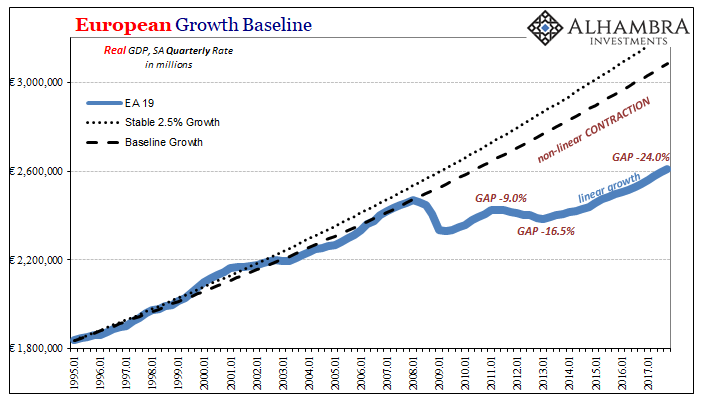

To start with, real GDP has been expanding for 19 straight quarters now. The last time the economy was in recession was five years ago during the first quarter of 2013. This sounds like an impressive record given so many challenges over that period.

Not only that, GDP accelerated in 2017. Over the last five quarters (through Q4 2017), growth hasn’t been less than 0.59% (Q4 2017). European GDP is calculated on a seasonally adjusted quarterly rather than annual basis, so that translates into about 2.4% as a floor. Five in a row above that level compares to the prior five quarters where 0.51% was the best among them.

These are not, however, in any way a basis for suggesting a booming economy. Far from it, they tell a very different story where when everything is apparently going right (globally synchronized growth) Europe’s economy can only manage low 2’s. That’s not good, and should be very concerning as to where the ceiling is – which ultimately matters more than the rest of the variables.

What’s really driving the narrative about Europe’s boom is PMI’s more than anything. After ignoring the manufacturing sector during the 2015-16 global downturn, PMI’s within it have exploded since “reflation” started in the middle of 2016 and are all over the mainstream news. Over on that side of the Atlantic, the numbers are truly astounding leading many to believe the economy has to be, too.

An index measuring output, which feeds into a composite PMI due on Thursday and seen as a good guide to economic health, rose to 62.2 from November’s 61.0 – its highest in over 17 years and has only been above that once in the survey’s history.

“The euro zone manufacturing boom gained further momentum in December, rounding off the best year on record and setting the scene for a strong start to 2018,” said Chris Williamson, chief business economist at IHS Markit.

That was in regard to the final PMI measure for December 2017, released in early January. The estimates for last month were down only a little from them, suggesting to many that the European boom has legs.

In 2017 the bloc’s economy was a surprise global star and any signs the energy, alongside rising price pressures, has carried into this year will be welcomed by the European Central Bank as it moves to unwind its super-loose monetary policy.

And so we have a major disconnect, and dissonance, between record PMI levels and growth that is better than before but not meaningfully so. PMI’s are suggesting records, GDP and so-called hard data a very long distance from it. Unsurprisingly, the narrative is built upon only the latter (where “the highest in 17 years” easily feeds into it in a way answering questions about tepid overall growth does not).

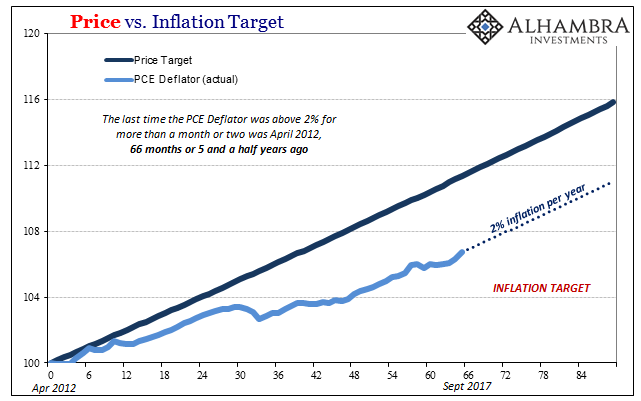

The ECB, however, cannot ignore the glaring difference, as much as it may try. After all, their first mandate like other central banks is for inflation as much as unemployment. In the big picture, this is a matter about what a central bank does, or should do. What I mean by that is what you see on the chart above. Never mind the statutory language and the legal mandates, does the ECB bear any responsibility for closing that massive gap?

In their view, they do only insofar as inflation stays underneath their target – as it has. Thus, so long as that is the case, they are forced no matter how reluctantly during any so-called boom to consider the possibility. This is why the inflation debate is so very important as a whole lot more than consumer prices alone. It is a signal that “something” isn’t right, still, even as PMI’s might suggest, and allow many to widely state, a booming economy on the threshold of overheating.

Another way of putting it is in the context of ECB policy where its job isn’t done simply because that job was never done (properly). By all these other counts, Europe’s economy is booming except right where it should be. That’s not something the central bank can ignore, though I have very little doubt Mario Draghi and his fellow policymakers are trying very hard to (like their Federal Reserve counterparts who can’t figure this out, either).

This is why, more quietly, central banks have been holding very serious discussionsabout these kinds of shortfalls. Among them is the idea of reflation itself in the policy setting. That means, for a central bank, not an inflation target but rather a price target or even an NGDP target. The point is recognizing that sustained weak growth and undershooting inflation cannot simply be set aside. It is the basis for so much continued dovishness, the persisting, nagging feeling even among the permanently optimistic among them that a great deal more still needs to be done (though it will take them a lot longer to figure out what that really is).

In the latter, as different from an inflation target, the central bank will allow, even contribute to, much hotter inflation so as to at least attempt to reduce that gap – even though they might otherwise claim the difference between the current trend and the prior one doesn’t any longer matter. They can tell themselves that, but all these basic aggregates like inflation keep showing them it does – a lot.

Or, as I wrote a few months ago:

We can’t get too hung up on the fact that the central bank wants to harm consumers at the worst possible time, that’s just their methodology of working through money to economy. In this case it’s actually progress because again they are being forced to recognize that inflation is behind, bringing them closer to the realization that it’s not just consumer prices that are desperately lagging (and then the big one, why that is).

A record PMI is in the end a hollow measure if it doesn’t translate. That’s where we are now with Europe, the United States, and the rest of the global economy. Growth is relatively better now than certainly 2015-16, but it still doesn’t add up to actual growth. There’s quite a lot missing that in less hysterical context becomes obvious.

Policymakers are therefore dovish by default, and they have a hard time reconciling it especially given the amount of time involved. Nineteen straight quarters of growth without growth really means there should have been growth long before now. As Mario Draghi put it recently by stating this stark contradiction:

The strong cyclical momentum, the ongoing reduction of economic slack and increasing capacity utilisation strengthen further our confidence that inflation will converge towards our inflation aim of below, but close to, 2%. At the same time, domestic price pressures remain muted overall and have yet to show convincing signs of a sustained upward trend.

In short, everything looks right even though its clear something is still very wrong. If only it was as easy as a PMI.

Disclosure: None.