Output, Employment And Unemployment: Some Updated And Some New Results

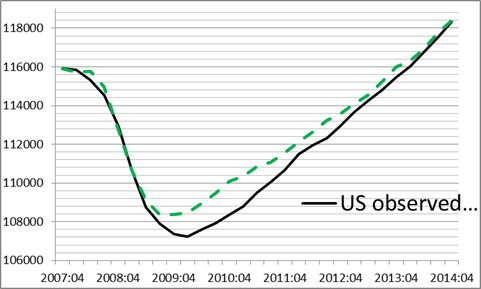

In a previous post, Laurent Ferrara, Valérie Mignon, and I examined the nonlinear relationship between employment and output (based on J.Macro (2014)). Using the most recent data, the level of (establishment) employment now matches the output level. Figure 1 shows the actual level, and the predicted level from a nonlinear error correction model.

Figure 1: Actual employment (black) and prediction from nonlinear error correction model.

This does not mean that employment is at full employment levels; rather it means that the long run relationship between employment and output has been restored. To the extent that output remains below potential, then employment is still below the corresponding natural rate.

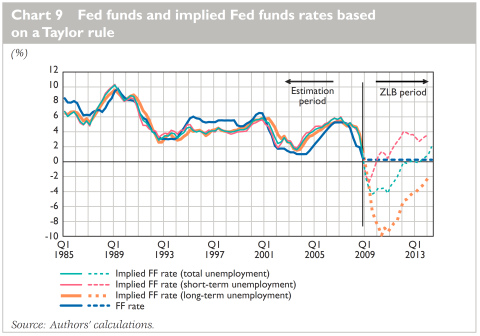

On a related note, Laurent Ferrara and Giulia Sestieri observe (in “US labour market and monetary policy: current debates and challenges”) that the historical relationship between the target Fed funds rate and inflation and long term unemployment indicates a current target rate that remains below zero.

Chart 9 from L. Ferrara and G. Sestieri.

From the article:

This Chart confirms what Janet Yellen has repeated a number of times in her speeches, especially during the period of quantitative forward guidance from December 2012 to December 2013, namely that the unemployment rate is not the only variable to be taken into account by the FOMC in its monetary policy decisions. Indeed, the prescriptions of a standard Taylor rule, based on the total unemployment gap, would have implied a rate increase from the second half of 2013, while a measure of the short-term gap would have implied a rate increase already in 2010. At this point, the specification using the long-term unemployment rate would still prescribe a negative policy rate.

These observations are particularly relevant, in the context of Chair Yellen’s recent speech:

Under normal circumstances, simple monetary policy rules, such as the one proposed by John Taylor, could help us decide when to raise the federal funds rate.3 Even with core inflation running below the Committee’s 2 percent objective, Taylor’s rule now calls for the federal funds rate to be well above zero if the unemployment rate is currently judged to be close to its normal longer-run level and the “normal” level of the real federal funds rate is currently close to its historical average. But the prescription offered by the Taylor rule changes significantly if one instead assumes, as I do, that appreciable slack still remains in the labor market, and that the economy’s equilibrium real federal funds rate–that is, the real rate consistent with the economy achieving maximum employment and price stability over the medium term–is currently quite low by historical standards. Under assumptions that I consider more realistic under present circumstances, the same rules call for the federal funds rate to be close to zero. Moreover, I would assert that simple rules are, well, too simple, and ignore important complexities of the current situation, about which I will have more to say shortly.

The speech is also discussed at length by Tim Duy. My argument for why monetary policy should not yet be tightened here.

Disclosure: None.