Why Inflation Protection Doesn't; Gold; Hyperinflation; Cataclysm

Inflation hits hard. At the start of the Seventies, if you were a retired company director on a fixed pension, you might well have been driving a car. By the end of the decade, you might have been on the bus, instead. And so, in the wake of the "oil price shock" and other inflationary factors, governments felt obliged to start protecting pensions and social security benefits.

But just how well does inflation protection work?

That's a can of worms. Official calculations use a variety of notional baskets of goods and services and probably none of them quite matches the way you spend your money. Besides, there are dodges like hedonic adjustments: for example, if a new computer costs the same as your old one, but has twice the memory, its notional price could be deemed to have halved, even if the extra power makes no difference to you - we're not all gamers and streamers.

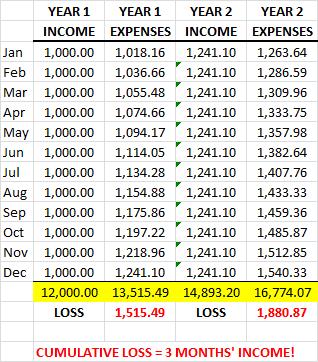

Still, let's say that the government does get it exactly and fairly right for you, uplifting benefits annually. You still lose, and here's why. Let's assume that inflation happens steadily over the year, and let's take the UK in 1975 for example. The figure for price inflation in that year varies according to source, but we'll use the 24.11% annual rate given on this site. Imagine that you earn and spend 1,000 monetary units per month, and at the end of the year your income is adjusted in line with RPI. Here's what happens:

At that rate, in 8 years you have lost a year's income; in a working lifetime, the income-multiple equivalent of a house. And that's when the government gets it right.

Or, your employer. No wonder the 1970s (and before) were bedevilled by industrial action. It wasn't all revolutionary socialists fomenting trouble - so many disputes (as I recall from news broadcasts at the time) were about the indirect effects of inflation: the struggles for (a) pay parity with other similar groups of workers and (b) pay differential.to reflect the additional value of more highly skilled work.

But as we see, even inflation protection isn't what it says.

And that's when the government is minded to protect - it withdrew Inflation Linked Savings Certificates in July 2010 (after 35 years of issues), re-offered them a year later and then closed the window again after four frenzied months during which savers jammed in to buy them.

Isn't it odd that central banks actually set an inflation target?

Wikipedia (yes, I know, but) says inflation targeting is about maintaining price stability "to support long-term growth of the economy". Funny how we didn't need it during the Industrial Revolution. The Bank of England's inflation calculator shows that prices over the 150 years from 1750-1900 rose only about 80% in total, or 0.4% per year - and not as a matter of policy.

Now, in our sinking economy, the target is 2% per annum - five times higher. And the BoE calculator says that in the 20th century we had an average 4.4% annual inflation (7202% total). We've had 54% cumulative inflation since the Millennium alone.

So, is gold overpriced? In 1900, an ounce of gold cost £18.96, and today (19 March 2017) it's £985.04. It's gone up 52 times, while prices using that BoE app have risen 112 times in the same period. Does this prove that gold is a bad investment, or could it be that the price is merely being suppressed until the financial system cracks? Some say the central banks will massively revalue gold when it suits them, which will remedy their deficiency in assets. Others say the US will be flooded with dollars when the greenback ceases to be the world's trading currency; Hugo Salinas Price says President Trump's attempts at protectionism will hasten the approach of that day.

The thing is, since we invented Magic Money nobody knows the proper price of anything. The trillions given to banks have gone into boosting asset prices and lowering the yield of government bonds. The latter effect is busting pension funds. Trouble is brewing: the rich are even now preparing boltholes round the world for just-in-case.

Most of us will know about the German hyperinflation of 1923. Supposedly the US' present alternative system of not printing its own money but borrowing it from a privately-owned Fed imposes discipline; but that discipline was found wanting when Henry Paulson demanded $700 billion from Congress (for starters!) and made it vote again when it said no. Democracy went thataway, folks.

Now, anecdote:

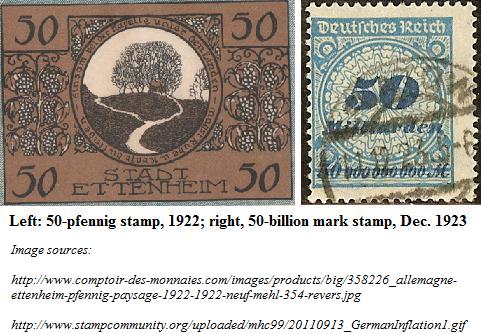

Our Dad was a philatelic collector in his spare time. We remember the bowl of lukewarm water soaking the paper, and the careful lifting-off with the tweezers, the stamp resting on the edge to dry before storage in the cellophane pockets of the album.

He had a great German collection. In 1918, delivery of a 20-gramme letter cost as little as 5 pfennigs (5/100 of a Mark, in their old money), but postwar inflation boosted that cost 10 times in only four more years.

The real fun started in 1923. I noted that some of our Dad's specimens were overprinted in Gothic type, and a few included the word "milliarden", which I supposed was German for "million". Wrong: it means "billion" - a thousand times a thousand times a thousand - Marks!

Adam Fergusson describes what happens When Money Dies - the middle class bartering the family piano for a side of meat to keep body and soul together. And what happened afterwards? War, atrocities, Russian invasions, Communism in China and so on.

The theft of stored value, whether slow or fast, is not trivial.

Disclosure: Nothing here should be taken as personal advice, financial or otherwise. No liability is accepted for third-party content, whether incorporated in or linked to this blog; or for ...

more